Football Halftimes Through The Years

The star-studded extravaganzas performed during Super Bowl halftimes are a far cry from those of halftimes past. Early on, football's halftimes were shorter, offered little or no entertainment, and generally occurred in locations lacking facilities for fans to refresh or defresh themselves. The 2022 Super Bowl is a different story and will last four-and-one-half hours, including pre-game ceremonies, sixty minutes of game clock, a thirty-minute halftime, and innumerable commercials. Of course, halftimes were not always so.

American football began with two forty-five-minute halves and a ten-minute intermission. The halves became thirty-five-minutes in 1894 before settling in at thirty-minute halves in 1912, each split into fifteen-minute quarters. Of course, the game moved along more quickly in the early years. Only the referee could call a timeout, the clock did not stop when the ball went out of bounds, and incomplete passes were decades in the future. Teams also lined up immediately after each play, called the signals at the line, and soon snapped the ball. The combination meant a ninety-minute game typically finished less than two hours after starting.

Despite the fast-paced game, halftime only took ten minutes, compared to twelve minutes for today's regular-season NFL games and fifteen for the colleges. Still, halftime activities have changed substantially since the beginning. Early football was played in open fields or small stadiums without locker rooms leading to the teams heading to opposite ends of the field at halftime to lie down, rest, and listen to a few coaching points.

The situation has changed for spectators as well. While we know the 1880 Yale-Princeton game at the Polo Grounds had a vendor selling alcoholic beverages from a tent just beyond one goal line, the first permanent concession stands did not arrive in stadiums for another thirty years. That meant halftime food and beverages were BYO or purchased from independent vendors hawking their wares among the crowd.

For those seeking entertainment rather than eats, formal or sanctioned halftime entertainment was also hard to find. Students sometimes performed a serpentine or snake dance, but those generally came postgame to celebrate a victory rather than mid-game.

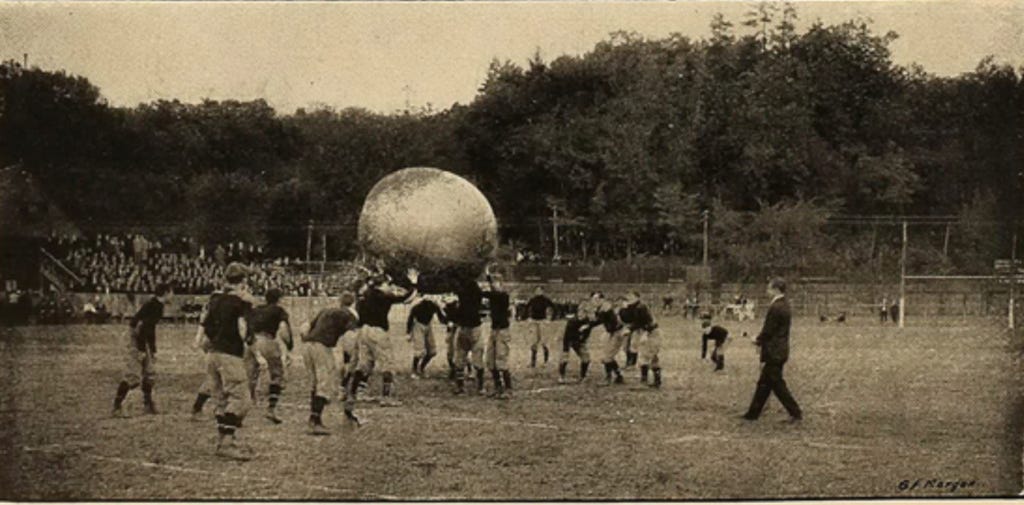

A host of halftime entertainment were tried at one location or another. Acrobatic flying exhibitions and parachutists, Native American dances, javelin throwing demonstrations, and cross country races that began and ended inside the stadium each received a trail or two. Among the more popular activities in the first decades of the 1900s was push ball, which substituted for interclass football games between the freshmen and sophomores at a few schools. Push ball was as much amusement as a sport for its players, besides providing a diversion for spectators of the main event.

The period before WWI saw the beginnings of the halftime activity most closely tied to college football: marching bands. Originating as student cadet bands near the end of the 1800s, Army, Navy, Minnesota, and Purdue had active bands by 1907. The popularity of bands increased dramatically after WWI as veterans with military band experience returned to campus, and music education became common in high school curricula. According to the bandies at Purdue, their marchers were the first to break ranks to form a non-columnar shape on a football field when they created a Block P in 1907.

Like orchestras and big bands, marching bands had the advantage of creating enough volume to be heard over the crowd before loudspeakers came along. (Likewise, soloists did not perform the pre-game national anthem until loudspeakers systems could amplify their voices.)

With their ups and downs and catches and drops, baton twirlers expanded many bands' repertoire in the 1930s. Prior to that time, males set the band's pace by twirling rifles and maces, but drum majorettes started assisting drum majors before losing their functional role and transitioning to twirling the lighter, rubber-tipped batons we know today.

Not only have marching bands dominated the in-stadium halftime experience for the last century, they also filled the screens of televised games until the 1980s. Before then, since the networks only televised one or two games per day, they lacked highlight footage of other games to show at halftime. They also lacked the technology to share such footage across the airwaves, so viewers at home tracked the bands as they marched across the small television screens of the day.

Of course, all this brings us to the Super Bowl, which followed the college script early on in that marching bands from nearby colleges provided the primary halftime entertainment for the first decade of Super Bowls. Audiences then enjoyed fifteen years of Up With People or pop stars supported by college bands before the NFL realized that nothing succeeds like excess, leading to the 1991 show headlined by New Kids On The Block, which set the direction for the many superstars and ensembles that followed.

Although the Super Bowl's halftime entertainment is eagerly anticipated and widely discussed, only a few college bowls or championship games have followed the Super Bowl's lead and targeted their halftime festivities at casual fans. Most college and high school halftime festivities have seen little change over the last century, with many playing the same traditional tunes. And that, of course, is a part of the atmosphere and attraction of most games, not the performances of the star-of-the-moment promoted by the NFL.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.