1927 and the Confusing World of Goal Lines

A 1927 rule change resulted in the fear that players and fans would struggle to distinguish the goal line from other lines on football fields. That fear led folks across the country to address the problem, with several of their solutions remaining part of the game today.

Since football's beginning, the goal lines were white stripes marking the ends of the field and the location of the goal posts, but the goal lines stopped marking the ends of the field when the game added end zones in 1912. Before legalizing the forward pass in 1906, football did not need end zones because the only way to score a touchdown was to carry the ball across the goal line. End zones still were not required when the forward pass became legal because passes that crossed the goal line on the fly or bounce resulted in a touchback. Pass receivers could score a touchdown only by catching the ball before the goal line and carrying the ball across the line.

As part of liberalizing the passing rules in 1912, the rules committee allowed passes to cross the goal line. They also added "end lines" ten yards behind the goal lines to define the "end zones." Unfortunately, marking the end zones made the field 130 yards long rather than 110, which meant a full-length field would not fit in some stadiums, particularly the many baseball stadiums that hosted football games. The committee quickly fixed that problem by eliminating the 55-yard line, resulting in our 120-yard long field. (As described here, Canadian rugby / football kept the 55-yard line it had adopted from the U.S. in 1903 but chose a twenty-yard end zone when they legalized the forward pass in 1929.)

After adding the end zones, players could easily distinguish the goal lines from other lines because the goal posts remained there. Nevertheless, the goal posts being on the goal lines was problematic because players sometimes ran into the goal posts when crossing the field on passing plays. The goal posts also obstructed some rushing plays and were problematic when punting out of the end zone.

However, the main problem with the goal posts being on the goal line was that the location encouraged teams to attempt field goals rather than pursue touchdowns. Football in the 1920s was in the final stages of evolving from a rugby-like game that valued kicking and rushing to a sport emphasizing rushing and passing. That evolution brought new rules, including the 1927 rule shifting the goal posts to the end line, thereby adding ten yards to each field goal and extra point attempt. Making those kicks more difficult made teams more likely to run or pass for a first down or touchdown, especially given the inaccurate straight-ahead kickers of the day.

The shift led many football aficionados to believe fans and players would confuse the goal line and end line. Though the idea seems silly now, folks in the Twenties experienced a different football field than ours today. Their football field was plain, marked only by sidelines, yard lines, end lines, and goal lines. There were no hash marks, Lockney Lines, logos, decorated end zones, or anything else disturbing the simplicity of the football field. Lacking the many visual cues we have today that differentiate the goal and end lines, football authorities across the country got busy devising new means to distinguish the two, and several of their solutions remain with us today. Others evolved from their 1927 beginnings, while a few disappeared and faded from memory.

Perhaps the most impactful change in marking football fields in 1927 came from decorating the end zones so they were visually distinct from the rest of the field. Decorated end zones are ubiquitous now and became the primary method of identifying the location of the goal lines, but before 1927, few, if any, end zones had decorations. Harvard painted diagonal stripes in their end zones, while several Southern schools added checkerboard patterns. Diamond patterns, school names, nicknames, and the like came along over the years. Team colors and logos now dominate most end zones, with the decorations limited only by the rule prohibiting the decorations from touching the white goal lines or other boundary markers.

A second method of distinguishing the goal line came by painting yard-line numbers on the field. For years, signs hanging on the front of the bleachers or standing along the sidelines identified the yard lines, but 1927 brought the first use of field numbers (numbers or symbols painted directly on the field). Yale marked their goal line by chalking a "G" on the turf, while Princeton stenciled a zero at the goal line. Not to be outdone, Harvard positioned a sign with the letter "G" and a tall pole flying a white pennant at the intersection of the goal line and sideline.

A third means of distinguishing the goal line was to widen the goal line stripe; an approach used intermittently since then. The 2021 NCAA Football Rule Book tells us the yard lines must be white and four inches wide. Sidelines and end lines may exceed four inches in width, while goal lines may be either four or eight inches wide.

The engineers at Georgia Tech took a fourth path to distinguish the goal line by placing "cushions" at the intersection of the goal lines and sidelines. Others marked the intersection with a pennant mounted on a tall pole or a flag mounted on a spring. (Those goal line flags are the reason today's corner route was known as the flag route back in the day.) The flags proved valuable and popular, leading the NCAA to mandate their use in 1940. They remained in place until the NCAA permitted pylons in 1966 before making the latter mandatory in 1979.

Another solution used for twenty-plus years was to add a second or twin stripe in the end zone, one foot behind the goal line. This approach was common enough that clever newspaper reporters referred to ball carriers "crossing the double stripe" when describing touchdown runs. Most everyone understood the first stripe was the official goal line, and the second was just a decoration. Still, at least one linesman did not get that message and failed to award a touchdown to a high school team that crossed the goal line but not its decorative twin.

The most unusual means of highlighting the goal line came from schools that planted short cardboard markers along the goal lines. Vanderbilt used them during the 1929 and 1930 seasons, while Oregon State and Florida did so in 1936. Of course, the markers were trampled during play, and it is not clear whether the ground crews replaced the affected markers or left them as is. Despite being used in several locations, the cardboard markers did not catch on, and a modernized version of the concept never developed.

The final method of distinguishing the goal line from the yard lines was to paint the goal line in a color other than white. Before the 1927 season, Walter Eckersall, the Chicago Tribune writer, suggested painting the goal line red and planting eight-foot poles with flags at the goal line extended. Despite Eckersall raising the issue, it is unclear whether anyone of the era used a non-white goal line. Colored goal lines go unmentioned in period publications, and the black-and-white photographs of time do not aid the search. However, Tulane's athletic director, Dick Baumbach, ordered gold goal lines for the Green Wave in 1955. Since Tulane Stadium hosted the Sugar Bowl until 1975, the gold stripe gained attention and acceptance, leading the rules committee to recommend their use in 1961. Some schools switched to the gold standard, but the gold stripes lost their luster and faded away.

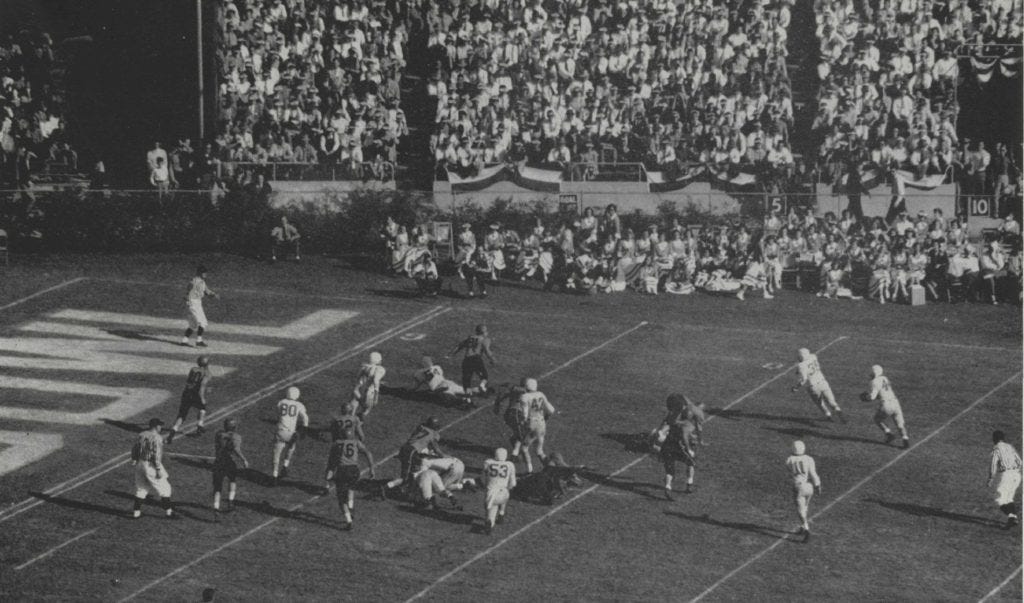

As seen in the images above, most locations used multiple visual cues to distinguish their goal lines. Still, even the 1961 Sugar Bowl's decorated end zone pales in comparison to those of today. Despite the visual cues being less vibrant than today's, college football players since 1927 found their way into end zones with minimal confusion, and fans largely understood the new configuration as well. Nevertheless, many of the field markings and related equipment we take for granted today entered the game to address a perceived need in 1927. While some may now be redundant, each adds flavor to the sights and atmosphere of college football.

If you enjoyed this article, consider subscribing to my newsletter or check out my books.