1951 and College Football's First National Television Contract

Major college football today is defined by its television revenues. The vast television monies pouring into college athletics provide palatial training facilities, extended training and coaching staffs, enormous salaries, conference realignments, and have led to NIL. All can be traced back to 1951, when colleges and conferences ceded their television rights to the NCAA, resulting in a national television rights deal. Other than the 1906 season, when the forward pass became legal, no season has impacted the shape of college football today more than the 1951 season. So, let's take a look at what happened.

The television technologies of the late 1940s and early 1950s were primitive compared to today. TVs had poor resolution, and despite the limitations, the seventeen-inch screens of the top-end televisions were better than listening to the radio. Radio provided sound, while television gave us moving images. Live. Sometimes.

But poor-quality displays were not the only limitation; the technologies to transfer television signals in real-time from one city to the next were also in their infancy. As a result, most games were broadcast only in the town where they originated, so it made sense for each school to negotiate its broadcast rights. The technologies were changing rapidly, however. TV sets were improving, more stations joined the Columbia (CBS), National (NBC), and DuMont networks, and transferring signals across the American expanse neared reality. These improvements coincided with an explosion in the number of television sets sold in the United States, growing from 190,000 units in 1948 to 10.5 million in 1950.

Still, televising college football faced another significant hurdle. In 1949, almost every major football program broadcasted one or two games from the state's big city station, but many saw in-stadium attendance drop, which most attributed to television. At the time, schools made far more money selling tickets than from television rights, so football and television had a problem, leading the Big Ten to ban the televising of its games for the 1950 season. Televised games also appeared to hurt attendance at small colleges. This was significant because every NCAA member school -from the smallest liberal arts college to the largest state university- had the same voting rights in the NCAA of 1951 and the small fry did not want televised games to hurt their crowds.

Still, opinions were divided since some schools saw no or positive impact on attendance, leading Penn and Notre Dame to sign contracts to televise all their 1951 home games. However, they backed out of those contracts when future opponents threatened to cancel their games if the two moved ahead with televising their games.

In 1951, almost everything of consequence associated with the NCAA was run by volunteers employed at member schools. The NCAA coordinated game rules and championship tournaments in some sports but had little say on eligibility issues and no enforcement role. So, the NCAA formed a committee to formulate a national plan, including assessing whether and how television affected game attendance. Headed by Pitt's Athletic Director and coach, Admiral Tom Hamilton, the committee developed an innovative national broadcasting plan sponsored by Westinghouse. The 1951 schedule provided an attractive slate of games while also being designed to test how game attendance fluctuated based on which games were televised.

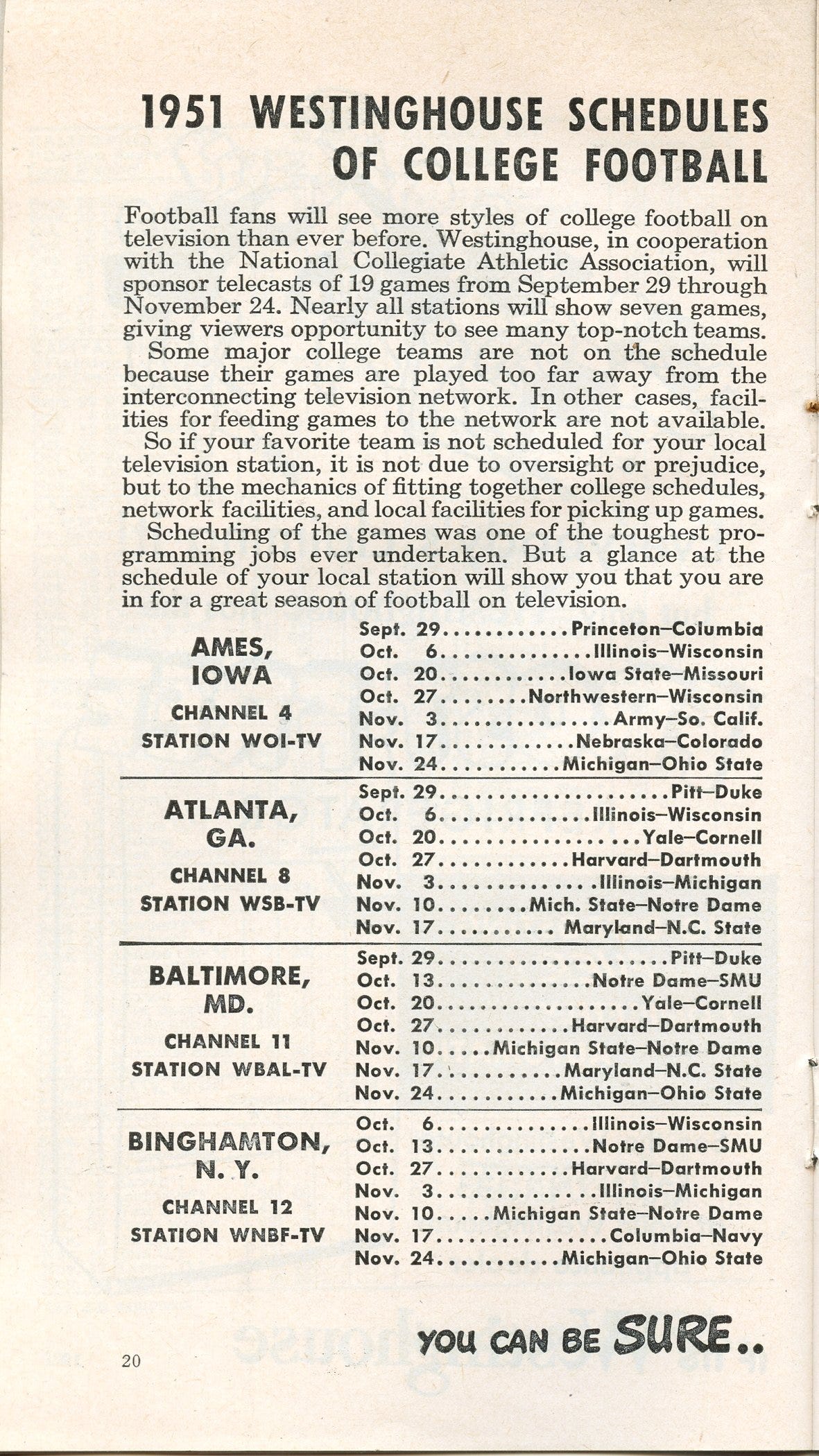

As it played out during the nine-week schedule, each station broadcasted one game on seven Saturdays and was blacked out on two weekends. Notably, the challenge of transferring video and sound from city to city had been largely overcome, allowing the Westinghouse schedule to include the first football games broadcast coast-to-coast. The table below shows the regions viewing each of the nineteen matchups. (Army-Navy and the bowl games were available separately.)

For fans in each of the NBC network’s fifty-two cities, the schedule looked something like this:

As mentioned in the second paragraph of the image above, some teams were left off the schedule because their games were played too far from an NBC network station or other technical limitations kept them off the air. The Westinghouse schedule did not include a game played south of Maryland or west of Nebraska. Only four games were shown in Salt Lake City, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego. So, the schedule involved teams from coast to coast, but it was not nationwide.

Fan reactions to the season depended on their previous access to televised games. Some saw more games than in the past, others saw less of their favorite teams, and everyone hated the blackout weeks. Protests by a few fan bases convinced the local stations to broadcast the hometown team's game when it was not supposed to be shown in their region.

In conjunction with surveys conducted by the University of Chicago’s National Opinion Research Center, the experimental results revealed that games involving teams from the same region as the viewers had the highest interest and depressed paid attendance more than nationally broadcast games. With this evidence and despite vehement disagreement from Penn and others, the NCAA moved forward in 1952 with a schedule based on national games of the week while limiting each school to one televised home game per season. Future blackout policies also received support from the 1951 season results.

More broadly, the 1951 television contract and season was a landmark for the NCAA. The NCAA television plan was the first instance in which schools and conferences ceded their rights to the NCAA and marked the beginning of the NCAA's transformation from an advisory organization to a powerful negotiating and enforcement agency. The NCAA controlled televised college football until 1984 when member schools sued and regained control on antitrust grounds. Since then, access to televised games has expanded exponentially, as have the associated dollars, particularly for teams in a few conferences. Where this leads is anyone's guess, but it all started in 1951.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.