A Brief History of Football's Extra Point

Although it seems entirely settled today, the process of scoring points following a touchdown has been among football’s most controversial issues, reflecting differences in the desired style of play among football's stakeholders. These differences resulted in dramatic changes in the number of points awarded and the process of earning those points over time.

Those of us living in the 21st Century know the point(s) after touchdown are less important than the touchdown itself. The touchdown is primary and counts six points, while the point(s) after is secondary, worth one or two points, but that was not the case when football began. The Intercollegiate Football Association meeting of 1876, which established American football rules, adopted England’s Rugby Code almost verbatim, with the most significant exception being the game’s scoring. Under the rugby rules of the time, the team kicking the most goals won the game. Rugby did not differentiate goals kicked from the field (field goals) from those coming from a free kick following a try (or touchdown). In rugby, the try (or touchdown) was not worth points. The try had value because it gave the offensive team an uncontested attempt to kick a goal. Rather than keep rugby's rule, the IFA reduced the value of goals after touchdowns by making them worth one-fourth the value of a goal from field.

The IFA eliminated its equivalency-based scoring system in 1883 when Walter Camp pushed for a point-based system. Still, since football was less than a decade removed from rugby, kicking a goal from field (via drop kick) was the most highly valued play and earned five points. A touchdown followed by a successful goal after touchdown play resulted in six points, establishing the precedent that the ability to cross the opponent's goal line mattered.

As shown in the table above, the shifting perspectives on the game led to the touchdown and goal after touchdown switching point values in 1887. Those who believed that crossing the goal line was the ultimate test of a team’s strength succeeded over the next twenty-five years in increasing the value of the touchdown and point after until the combination exceeded the value of two field goals.

In addition to changes in the points awarded, the process of executing the goal after touchdown saw numerous changes as well. Originally, the ball remained live after a missed goal after touchdown, meaning the kicking team could recover the ball over the goal line for another touchdown or on the field of play, after which it was first down. This led teams to deliberately miss kicks and attempt to recover the ball, until the rules of 1893 made the ball dead following a missed kick.

Until 1896, all kicks executed from scrimmage were drop kicks. That changed when two brothers who played for Otterbein wrote to Walter Camp about their idea for a new style of goal from field. Camp confirmed the legality of their approach, which had the center snap the ball to a teammate who placed the ball on the ground, holding it in position for the kicker to boot it. And so was born, the placement kick, often but mistakenly called the Princeton place kick because the Tigers popularized the technique invented by the brotherly Cardinals.

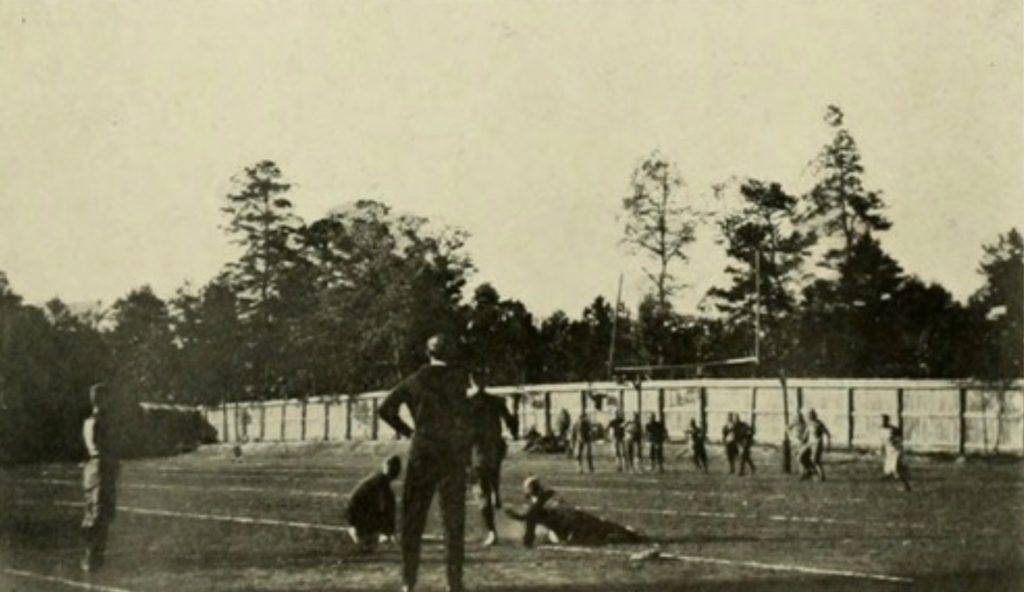

The placement kick became common when attempting field goals, but goals after touchdowns were free kicks. On free kicks, every player on the kicking team had to be behind the holder, who lay on the ground. The kicker's teammates sometimes moved to the sideline. Other times they relaxed on the field behind the kicker and holder.

A more dramatic difference between the drop kick versus the placement kick was the role of the puntout in executing the goal after touchdown. An earlier post covered the puntout in detail, so it is not repeated here. Suffice it to say that until 1920, the spot at which teams attempted the extra point depended on the point they crossed the goal line. Those crossing the goal line in the middle of the field kicked from the middle of the field, while those scoring near the sideline kicked from near the sideline, unless they opted to puntout.

With the elimination of the puntout, the rule makers gave the scoring team a free kick from anywhere on the field. The point-after rules were changed once again in 1922 with the scoring team receiving the ball at the five-yard line for a play from scrimmage where they had the choice to attempt the extra point via place kick, drop kick, run or pass with the defense contesting all four options. Offensive penalties on the attempt resulted in the offense losing the opportunity to score the point, while defensive penalties resulted in a point being awarded to the offense. The ball was placed on the three-yard line starting in 1924 and has shifted between the two- and three-yard lines ever since.

The final set of changes came in 1958 when the college rules committee sought to both reduce the number of tie games while also competing with the NFL's more exciting play style. To spice things up, they gave teams the option to earn two points by running or passing the ball across the goal line, an approach the NFL adopted in 1994.

Adding the two-point conversion was likely the savior of the goal after touchdown. The rise of soccer-style kickers in the 1960s made the extra point attempt nearly automatic. Had there ever been a time to eliminate football's original scoring method, that was it. Still, the two-point conversion adds a strategic dimension to the game that transcends its actual usage. It offers hope for teams trailing in games that the correct combination of touchdowns and conversions might yet yield a victory. That, in itself, is a reason for its remaining part of football.

Subscribe for free and never miss a story. Regular readers, please consider a paid subscription or make a small donation using Buy Me A Coffee.

Was the term "singleton" for an NFL point after touchdown conversion by run or pass, prior to the two point conversion a common usage? The only instance of the term for this type of play was in this highlight video by Pat Summerall. https://www.youtube.com/shorts/WjW7M_bgWgA

Thanks.

Thanks for the help. I can't believe that the term would have just been coined by the highlight show writers (or Summerall).