A History of Helmet and Face Mask Requirements

About two years ago, I wrote a story about the battle between plastic and leather helmets, mainly how that played out in the 1955 Spalding catalog, which offered four plastic helmet models and three in leather. Why would a manufacturer offer both versions when plastic helmets better-protected players' heads? The answer lies in the NFL and NCAA rules and football practitioners' beliefs about protecting the helmet wearer versus others on the playing field.

Our British cousins defined 59 rules when establishing the Laws of the Rugby Football Union in 1871. Rule 58 banned the wearing of equipment that might harm other players and read:

No one wearing projecting nails, iron plates, or gutta percha on any part of his boots or shoes shall be allowed to play in a match.

Despite gridiron football's evolution from rugby, the idea that players should not wear equipment made of hard and unyielding substances remained in the game. The rule-makers banned some versions of early headgear made of sole leather and generally emphasized the need to pad harder substances that made their way onto football fields. Early shoulder pads, for instance, were padded on the interior and exterior to cushion blows in both directions. Likewise, the original rationale behind football's rules requiring knee pads was not to protect the wearer's knees but the heads of opponents taught to tackle the wearer at the knees. (Football might not need helmets or knee pads if tackling is allowed only above the waist, as in rugby.)

Players, coaches, and equipment manufacturers largely complied with football's ban on stiffer substances until synthetic materials arrived. Nylon and other synthetic fabrics were used in some uniforms in the late 1930s until the Army started encouraging men to jump out of planes with nylon blankets strapped to their backs, at which point, the Army claimed the nation's nylon supplies. Riddell's plastic helmets first saw the field in 1940, though they took a similar vacation when war needs redirected plastic production.

The NFL and NCAA required helmets to be a different color than the ball to avoid the camouflage effect (a standard that still exists but did not directly address the issue of helmets potentially endangering others.

The NCAA required players to wear headgear in 1939, with the NFL following in 1943. Nevertheless, even NFL players were smart enough to wear helmets before that. Dick Plasman was the exception as the last NFL player to go without a helmet during the 1941 season. After returning to the NFL following military service, Plasman donned a leather chapeau to comply with the new rules.

With plenty of plastic to go around after the war, helmet manufacturers began selling plastic helmets with suspension or padding systems on the interior. Although football helmets were not tested for their protectiveness, everyone agreed that plastic helmets better protected the wearer than leather helmets. The problem was the impact of plastic helmets on opponents' bodies and faces.

As more teams began wearing plastic helmets, concern mounted about the danger they posed to others. The NFL banned plastic helmets in 1948, only to allow them again in 1949 under pressure from teams that thought their benefit outweighed the risks. The 1949 rules made an odd change by dropping the requirement that players wear head protectors, instead inserting a rule that:

All players must wear stockings and head protectors in all Championship, All-Star, and Charity games.

The rule suggests that NFL players could have gone without helmets in regular-season games, but no one did. [Note: A reader told me that “Championship” refers to league games that count toward the Championship, not the Championship game itself.)

On the NCAA side, following a Harvard quarterback who broke his leg after being hit by a helmet, Harvard's athletic director and rules committee chairperson, William Bingham, announced that the NCAA would ban plastic helmets starting in 1950. He did so without the committee's approval, which they never provided.

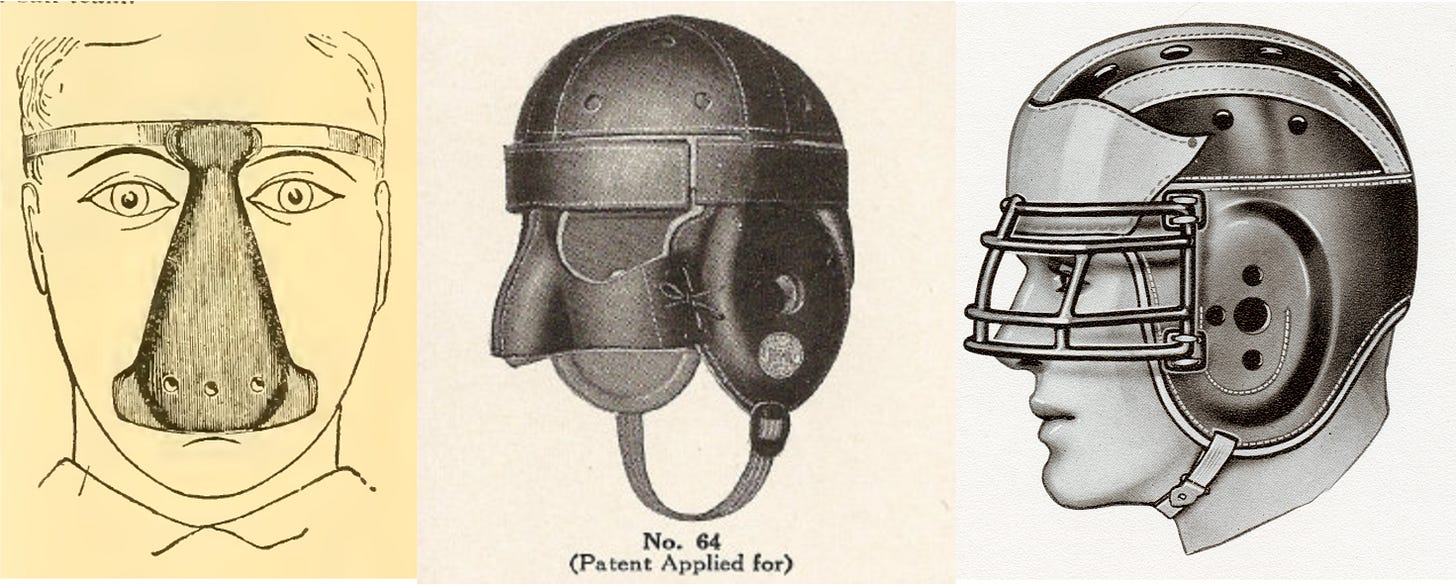

The adoption of plastic helmets grew rapidly, though a number of college coaches continued holding out, believing they endangered others. The 1950s also witnessed the increased adoption of face masks in the NFL and NCAA. Players wore nose guards starting in the 1890s, executioner's masks were commercially available in the late 1920s, and "bird cage" face masks soon followed.

Each of those products focused on protecting broken noses or preventing the same, and bird-cage masks also allowed players to wear eyeglasses on the field. Still, most teams had only a few players wear facial protection until plastic helmets became standard, which changed everything.

Plastic helmets striking opposing players in the face led to more lost teeth, broken noses, lacerations, and other injuries. Otto Graham of the Cleveland Browns famously wore a face mask after suffering a facial laceration, and others began wearing them to prevent rather than protect injuries. The NFL recommended that players wear face masks in 1955, with the rule book noting:

The use of RIDDELL plastic face guards (similar to those used by the Cleveland Browns in 1954) is suggested. Care must be exercised that no equipment is used that presents hazards as cutting, chipping, breaking, etc.

Of course, the increased use of plastic helmets and protruding face masks led to more facial injuries to those who did not wear face masks, so selected manufacturers designed and sold face masks that were more mask-like, resting on the face. Often made of clear plastic, they had cushions between the mask and face. Despite being worn by high-profile players such as 1954 Heisman Trophy winner Alan Ameche, they soon disappeared from the market in favor of single and double-bar face masks.

By the early 1960s, nearly everyone wore a face mask. The NCAA made face masking a penalty in 1957, as did the NFL in 1962. The NFL allowed players to gain exceptions to the face mask requirement, with All-Pro flanker Tommy McDonald being the last position player to go without one during the 1968 season. A few kickers and punters went maskless after that, but they don't really count.

At the college level, face masks were universally adopted despite one of the extraordinary oddities of NCAA rule-making. The NCAA did not require players to wear face masks until 1993. It may not have mattered since everyone wore one, but confirming the expectation a few years earlier might have been nice.

Although not directly related to requiring the wearing of helmets and facemasks, helmet logo adoption coincided with the universal adoption of plastic helmets. Helmet logos arrived by 1921, but few teams added logos on their leather helmets. Instead, they painted the forehead wings, straps, and the rest of the helmet in contrasting team colors.

For a decade, the TV number craze of the mid-1950s and conference TV number requirements kept logos off college helmets. However, as Noah Cohan argues, plastic helmets provided an uninterrupted blank canvas begging for logos, which the NFL and AFL adopted for television, sports licensing, and merchandising purposes.

College teams added logos in the second half of the 1960s and beyond. Bama’s TV numbers, Penn State’s blank slate, and the silver and golden domers aside, nearly every school now embraces its logo or logos. While the logos have not increased player safety like helmets and face masks, they have made them more attractive and marketable as team and football symbols.

Football Archaeology is a reader-supported site. Click here for options on how to support this site beyond a free subscription.

Last maskless player: Toni Fritsch - Nov. 7, 1971. Dallas 16, St. Louis 13. FGs: 3/4.

In the early '50s, maskless helmets caused skin-scraped cheekbones on tacklers called 'strawberries,' a status symbol.