A History of Logos on Football Gear

Note: If you support Trump and his fascist ICE goons, you are not welcome here. Leave and do not return until you find your heart and brain.

The NCAA’s Division I Cabinet recently announced that it will allow commercial logos on uniforms and apparel starting in August, just in time for the 2026 preseason practice and regular season. The Rules Committee will determine the details, but so far the logos cannot exceed 4 square inches or interfere with the officials’ ability to manage games. For example, the rules will restrict or designate where logos can be placed so they do not affect officials’ ability to read player numbers. While we wait with bated breath for those rules, let’s review the place of equipment manufacturers and other commercial logos in college football history.

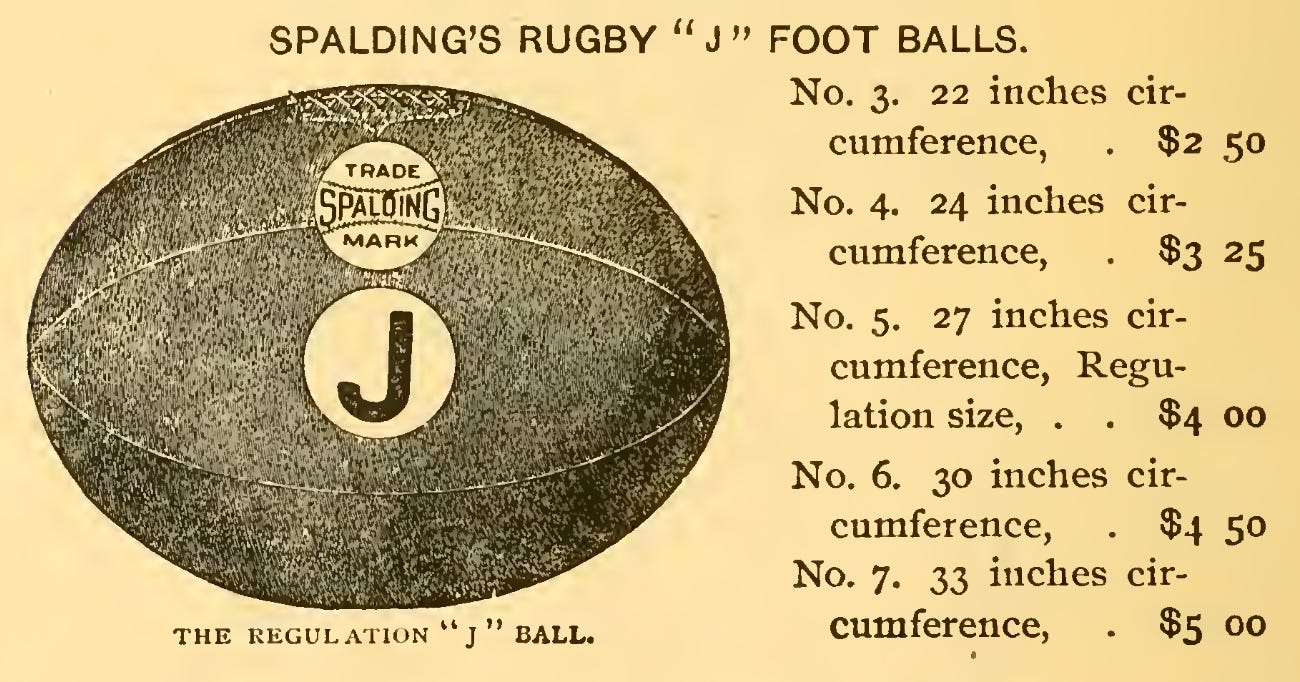

Equipment manufacturer logos have been a part of football since the beginning, or nearly so. Early Intercollegiate Football Association (IFA) rules required the use of the imported Lillywhite ball. Lillywhite balls sold in America bore their logo and that of their exclusive importer, A. G. Spalding. In 1892, the IFA designated the Spalding Model J as the official ball. It bore the Spalding logo, not so much to promote the brand as to prevent counterfeits.

Although everyone followed the IFA’s football rules, only a few teams were IFA members, so that the other teams could use balls made by Spalding’s competitors. Regardless of the manufacturer, each literally branded their ball, though their logos and other branding were not readily apparent to fans or anyone more than a few feet away.

College teams wore their school colors with team letters or logos, but other logos had little or no place in early football. Equipment manufacturer logos did not appear on jerseys or pants, except for tags with size, laundering, or other information placed in areas hidden from view.

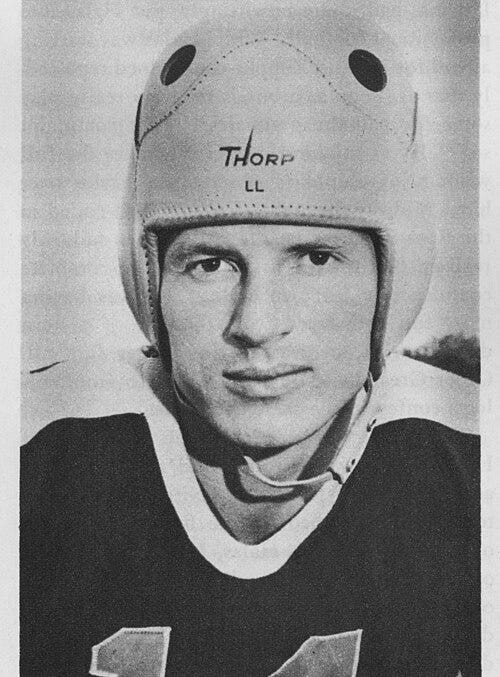

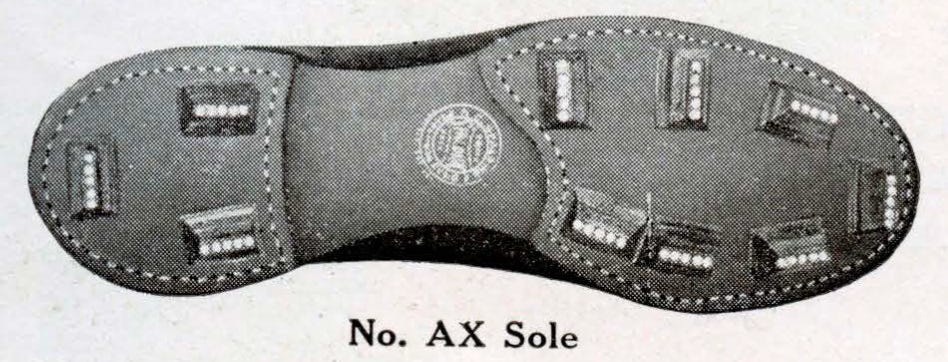

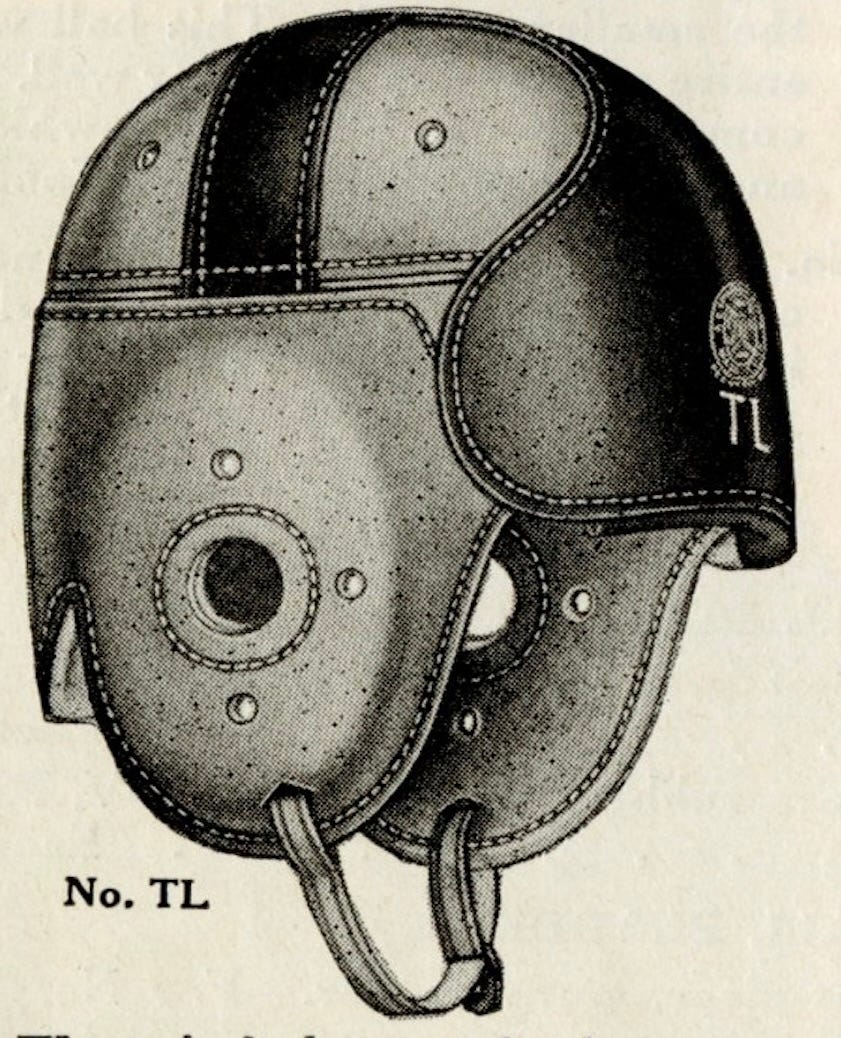

By the mid-1910s, manufacturers began placing logos on the soles of shoes and on the sides or backs of helmets.

Prominent coaches and players also had their names or signatures placed on products they endorsed, but none of these logos were highly visible. They authenticated the product rather than visually promoting the brand to fans.

The first relatively visible equipment brand logos were those appearing on helmet foreheads around 1930. While less prominent than today’s Nike swoosh or Under Armour’s UA logo, they set the stage for what was to come.

It is difficult to buy athletic apparel today that does not have a prominent brand logo. The shift in that direction did not begin until the 1960s, when adidas and Puma added prominent logos to their products and began paying soccer players and Olympic athletes to wear their products. Other brands followed, and similar pay-to-wear schemes came to the U.S. with professional athletes paid to wear a brand’s gear, and college coaches paid to ensure their teams wore a particular brand.

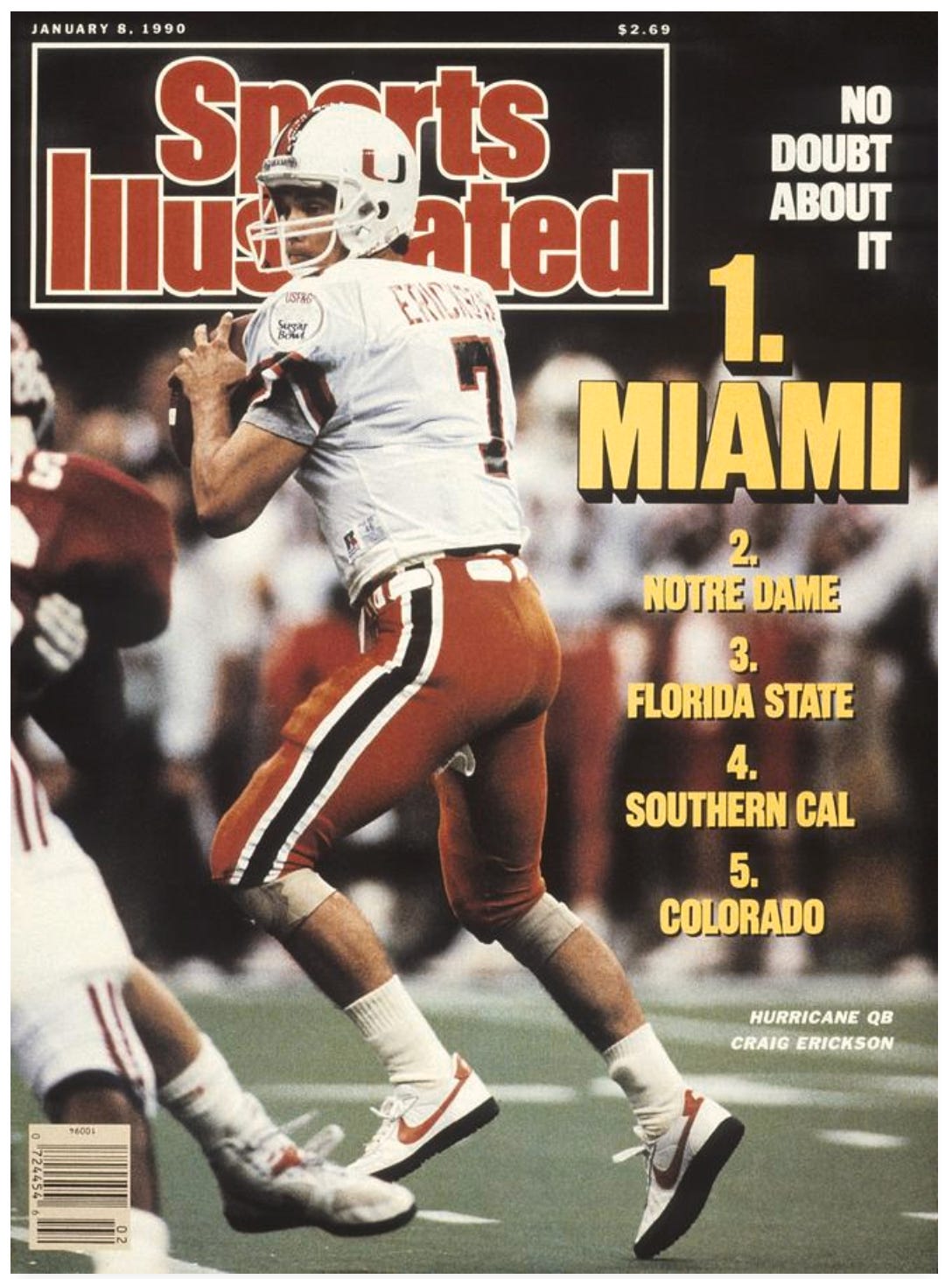

The brands quickly moved from paying individual players and coaches to broader agreements, such as Starter signing league-wide contracts in the early 1980s. On the college side, the arrival of the Collegiate Licensing Company in 1981 signaled that schools were taking control of the former coach-level deals and formalizing other licensing arrangements, leading to the university-equipment brand partnerships we have today.

The explosion of logos on uniforms and gear led the NCAA football rules committee to address the issue in 1987, placing a limit of one logo per shoe, garment, or other equipment, not exceeding 1.5 square inches, later increased to 2.25 square inches. The specific rules have been updated over the years to limit the number and location of logos. The 2025 NCAA rules address:

The number and location of logos on the field

Ban advertising on goal posts while allowing one manufacturer’s logo

Allow one manufacturer’s logo on pylons and down markers

Detail the 10 types of logos, or other permitted information on players’ uniforms other than the jersey numbers.

Historically, college uniforms and fields have not promoted commercial entities (non-equipment manufacturers). The exceptions to this rule include field logos for commercial entities with stadium or field naming rights, and patches on player uniforms for bowl games whose names include commercial entities.

Commercial logos have a longer history with athletic teams in other countries. Japan’s major league baseball teams have commonly been corporate-sponsored and named since the 1950s, leading to them appearing on uniforms. Commercial logos on uniforms appeared in European soccer in the 1970s and in the CFL in the 1990s.

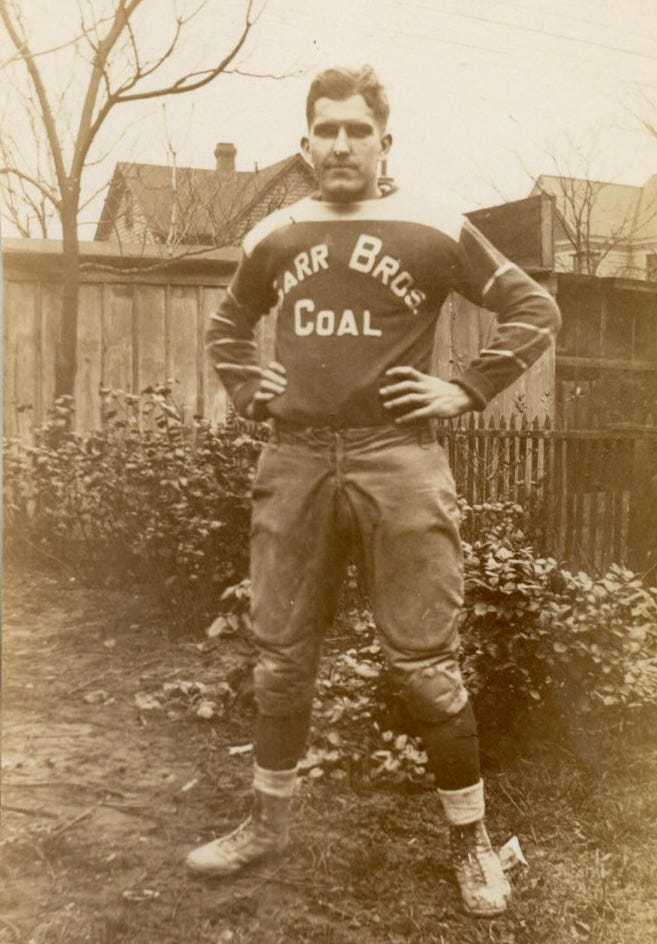

In the U.S., placing commercial names and logos on uniforms was common with semi-pro football teams, which often had sponsor names or logos on their jerseys or as part of their team names.

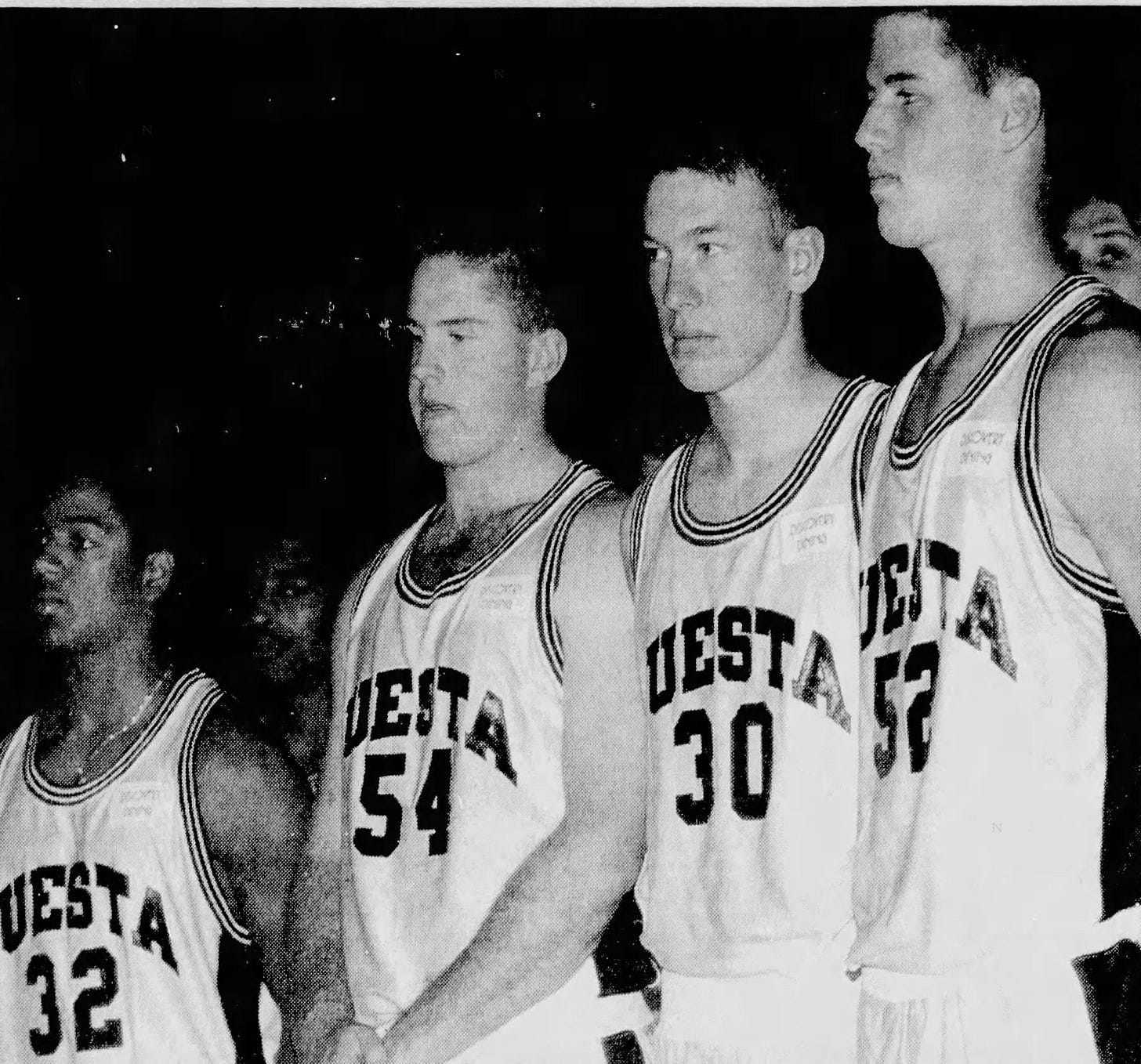

Cuesta College, a California junior college not subject to NCAA rules, put commercial logos on its men’s basketball uniforms in 1994 during a budget crunch. Still, it appears to be the only college team to have done so to date.

Otherwise, commercial logos are relatively recent arrivals to North America’s professional sports leagues. The NBA allowed them in 2017, the NFL and NHL in 2022, and MLB in 2023, and each heavily restricts their size and location.

Today, the NCAA and major college football have dropped all pretenses of it being a game played by amateurs. It is a professional game, so logos for insurance providers and anyone else willing to put up the money are coming to a homecoming weekend near you. We’ll complain a bit, then get used to it, the same way we accept TV timeout after TV timeout as a given. It will be interesting to see whether the NCAA restricts which logos can appear on uniforms. Will they allow alcohol producers, gambling sites, or religious or political entities? Who else might they limit? We’ll soon see.

Regular readers support Football Archaeology. If you enjoy my work, get a paid subscription, buy me a coffee, or purchase a book.

It wasn't just semi-pro football teams that had sponsor names on their gear; baseball, basketball and hockey teams at the same level also had sponsors on their apparel and as part of their names.

I find it interesting that NFL players are allowed to wear logoed shoes and gloves of their choice, and presumably be compensated accordingly. Not sure if that also allies to socks. Everything else they wear has to be Nike branded.

When Mike Nolan was head coach of the 49ers, he wanted to wear a suit on the sideline during games. His father, who also coached the 49ers had worn a suit during games. They had to work a deal with Reebok, which had the uniform contract at the time, to provide Mike Nolan’s suits, with Reebok branding on the lining.