A Look Back On Football's Transitive Property

Much of the fun of football and sports comes from the belief that my team is better than yours, and one way fans have convinced themselves that their team might win is through comparative scores. But, of course, comparative scores have their limit, and some comparisons are better than others. Still, the most straightforward ranking system and most sophisticated computer model both boil down to comparing one team's scores against another's.

Comparative scores cannot account for upsets and chance effects, matchups, injuries, doubleheader games with second teams losing to a lesser opponent, home and away games, or teams improving or declining during a season.

From the beginning, newspaper reporters using comparative scores recognized the process had faults and often inserted a caveat such as "If comparative scores mean anything..." Post-caveat, they plowed forward with the argument they planned to make anyway

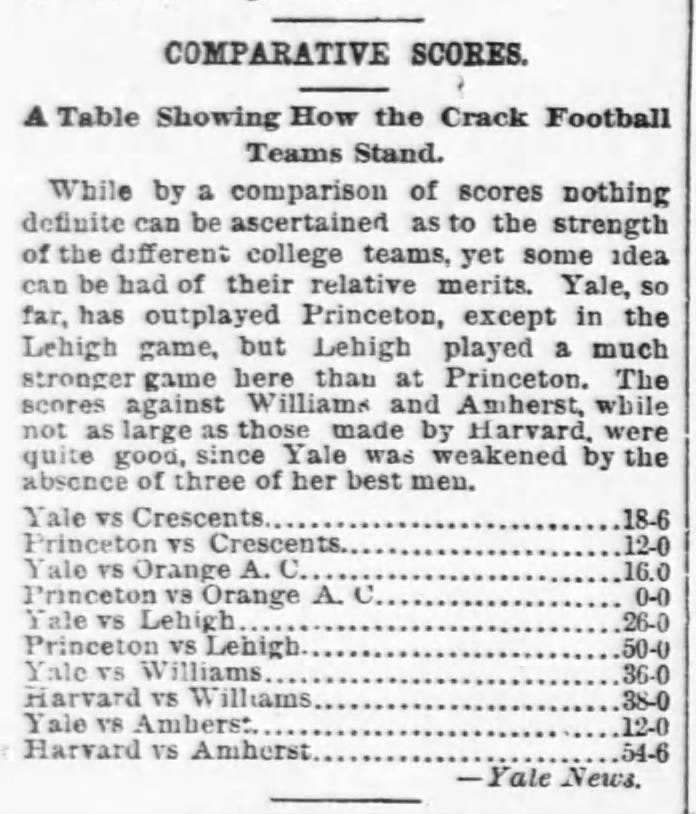

Early comparative score arguments typically involved comparing two teams' performance against common opponents, which seems reasonable, if not necessarily accurate. For example, a prediction about the 1890 Yale-Princeton used comparative scores. While the reporter acknowledged the approach was not foolproof, he suggested Yale was the superior team until Princeton demolished Yale 32-0 in the season-ender.

Another reporter in 1892 looked at how Northwestern and Wisconsin fared against Minnesota and Michigan to conclude the Wildcats would top the Badgers, only to see Wisconsin win twice, 26-6 and 20-6, in games played five days apart.

There were times when the comparative scores approach proved predictive, reinforcing their future use, mainly since few tools were available. For example, how else could they support arguments about conference championships when teams played only two or three conference games per year? When Georgia and Auburn tied their game in 1911, their supporters used comparative scores to argue which one deserved to be SIAA champs. Their alternative was to rely on conference win record, excluding ties, which often made less sense.

The outcomes of the Rose Bowl and other early intersectional games supported comparative scores arguments comparing one section of the country versus another. For example, Washington State beat Brown in the 1916 Rose Bowl, leading Cougars supporters to claim they were better than Yale, Harvard, and Princeton in 1915. Likewise, West Virginia's 25-0 victory over Princeton in 1919 led to mountains of comparisons of Southern versus Eastern.

The 1910s marked a significant turning point when a transitive property chain required only five links to show Maryville College was superior to Yale.

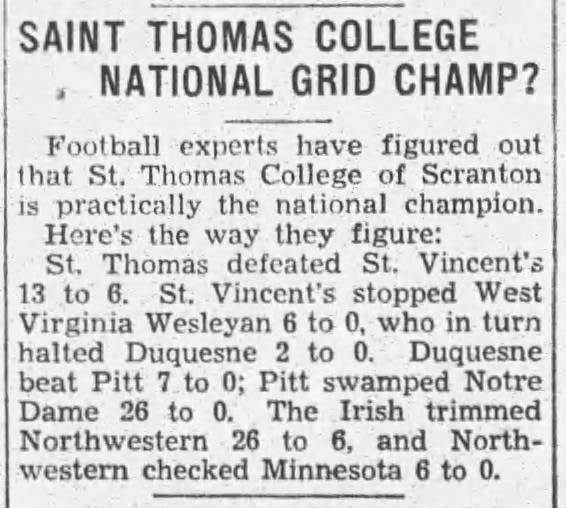

While made in jest, it illustrated how comparative scores and the transitive property could provide absurd results. Another application of the transitive property came in 1936 when seven links in the chain showed St. Thomas (now the University of Scranton) was better than the acclaimed national champion Minnesota.

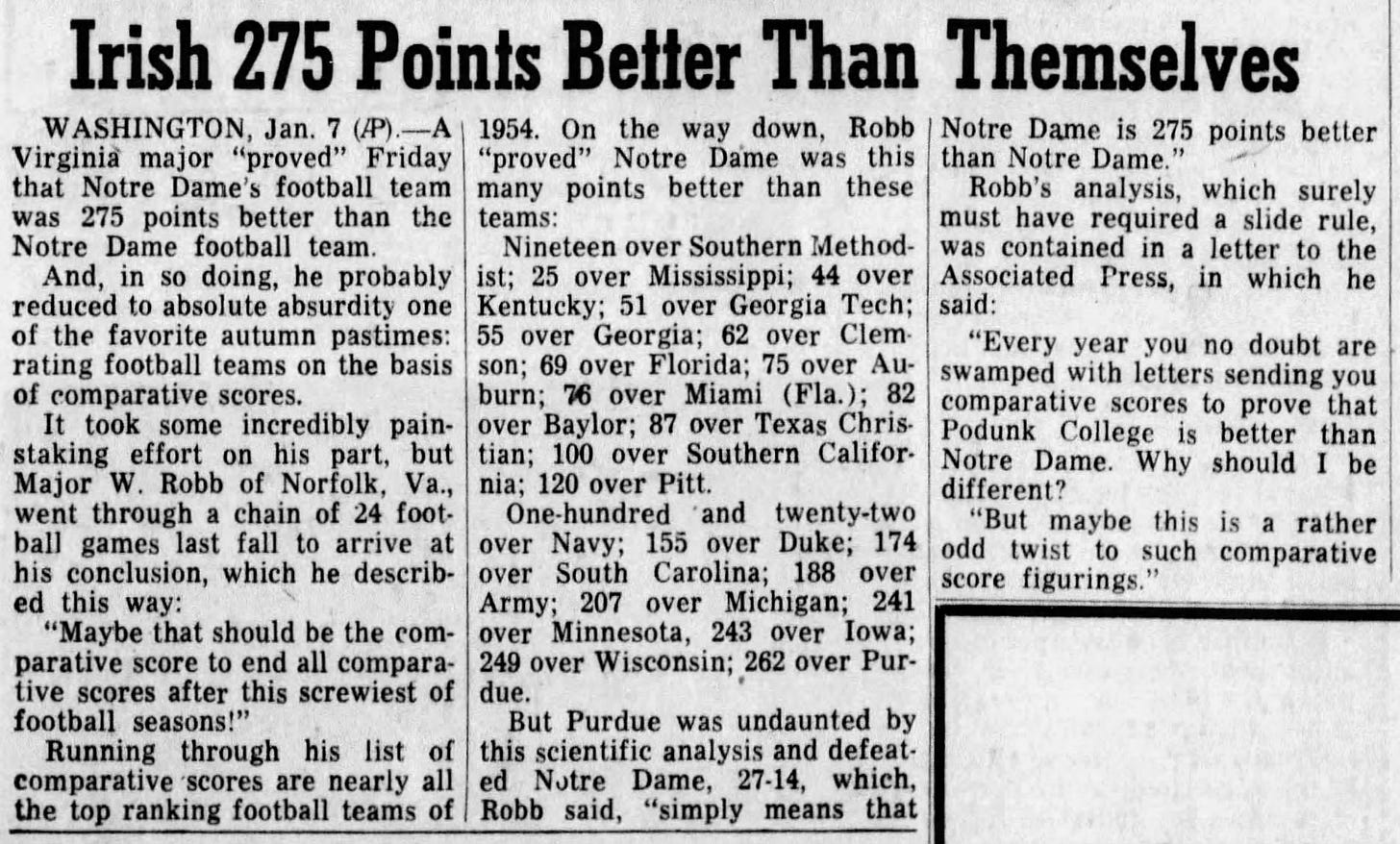

Perhaps the most impressive feat of transitivity came in 1955, when a fan, without the aid of a computer, used comparative scores to see how Notre Dame stacked up against other Top 20 teams. For example, he found the Irish were 19 points better than SMU, 100 points better than USC, 207 points better than Michigan, and 262 points better than Purdue. However, since Purdue beat Notre Dame that year 27-14, he argued the result proved Notre Dame was 275 points better than themselves.

Nowadays, we have college football teams divided into different divisions. That means the crossover games in which teams from lower divisions beat teams from higher divisions become critical to taking transitivity to its illogical conclusion. Despite that challenge, My Team Is Better Than Yours eliminates the calculation task, allowing you to show your team's superiority over almost anyone else, even if you are McMurry, which requires 36 transitive links to beat Georgia in 2022.

MTIBTY proves that three of my four alma maters' football teams were better than Georgia in 2022. Two play DIII football, so their paths to success are longer than my former home in FCS (36 and 27 versus 9), while the fourth school lacks a football team, so even MTIBTY could not find a superior path for them.

So, except for a few teams that I hope go winless in 2023, I hope everyone enjoys the 2023 football season and uses the transitive property to support their claims of superiority over their rivals.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.

Good sense of humor is employed here...