Terminology... Three Yards and A Cloud of Dust

—This is article #1 in a series covering the origins of football’s terminology. All are available under the Terminology tab above. My book, Hut! Hut! Hike! describes the emergence of more than 400 football terms.

Few expressions are more closely associated with a particular football coach than the link between "three yards and a cloud of dust" and Woody Hayes. Yet, while the two are tied together in people's minds today, they did not start that way. The original expression was not associated with Woody Hayes, referenced four yards rather than three, and was in reverse order. We'll cover how that change occurred in a moment, but let's first discuss clouds of dust on football fields.

As covered in an earlier article about the wretched field conditions of the past, old-time football fields were not watered and often became dusty, particularly out West, where the lack of rain left football fields with little grass. Other parts of the country also experienced periodic dry spells and played games in baseball parks where dust kicked up on the infield. So, dust clouds were a regular part of football in the old days and remain today.

Three yards and a cloud of dust is an expression of pride among those who play physical football and enjoy methodically marching down the field. Most use the expression as a pejorative for a dated, dull, and unimaginative style of play. That was its original use when it described the Split T offenses that dominated college football in the 1950s.

While teams found success using the Split T, college football's run-heavy, limited substitution game of the 1950s contrasted with the increasingly popular NFL that touted its star quarterbacks and pass-heavy game.

The Split T was the brainchild of Don Faurot, who introduced it at Missouri in 1941 as football's first option running attack. As in the Modern T, the quarterback aligned under center. His first post-snap movement was to give to or fake the quick-hitting halfback dive. (The quarterback called the give or fake in the huddle; it was not an option read.) After the give or fake, the quarterback continued moving parallel to the line of scrimmage, reading the unblocked defensive end. If the defensive end penetrated the backfield or moved outside, the quarterback kept the ball and turned upfield. Conversely, if the defensive end attacked the quarterback, the quarterback pitched to the sweeping halfback using an underhand toss.

Since the quarterback ran directly behind the line of scrimmage on the base series, he was within five yards of the line of scrimmage and could not legally throw a forward pass until the college rules changed in 1945. Even after the rule change, Split T quarterbacks remained too close to the line to pass effectively, so the halfbacks handled the passing, as they did in the Single Wing. All in all, the Split T was a run-heavy offense.

Faurot interrupted his tenure at Missouri to coach the Navy's Iowa Pre-Flight team in 1943, where his assistants included Jim Tatum and Bud Wilkinson, both of whom used the Split T as head coaches during the 1940s and 1950s. Wilkinson won national titles in 1950, 1955, and 1956 at Oklahoma, and Tatum won the 1953 title at Maryland. Other teams winning titles in the first half of the 1950s ran the Single Wing or run-heavy T formation offenses.

There were, of course, some who passed the ball extensively, including Cactus Jack Curtice. Curtice coached in Texas before taking over at Utah in 1950, where he proceeded to win the Skyline Conference in 1951, 1952, and 1953 with his pass-happy offense. For the next several years, however, he ran the ball more using elements of the Split T, which John Mooney, a writer for the Salt Lake Tribune, found boring and was happy to say so to his readers.

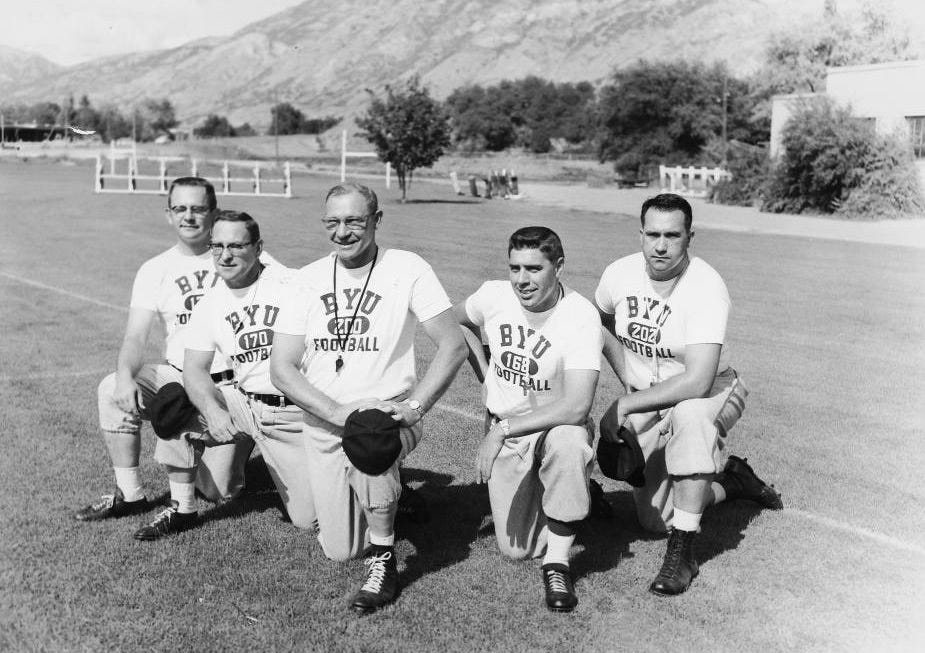

In an article leading up to the 1955 Utah-BYU game, Mooney mentioned that Max Tolbert, a BYU assistant, had referred to the Split T as "a cloud of dust and four yards." While Tolbert is the first person known to have used a version of the yardage and a dust cloud expression, it is unclear whether he coined the phrase or was simply the first to be quoted using it.

Mooney changed the line to "a cloud of dust and five yards," which he twice used in articles in 1956 and once in 1957, and then returned to the four yards version later in 1957. The expression also popped up toward the end of the 1957 season when Louisiana sports columnist, Jim Wynn, commented on Texas A&M's poor showing versus Texas, saying:

The Aggies showed little or no offensive imagination in the game with Texas. Texas A&M's passing attack was weak, almost to the point of non-existence. The big Aggies play was a quick three-yards-and-a-cloud-of-dust burst into the middle of the line.

Wynn, Jim, ‘Wynning Ways,’ Town Talk (Alexandria, LA), November 30, 1957.

This marked the first time "three yards and a cloud of dust" appeared in print. However, it is worth noting that the unimaginative Texas A&M coach in 1957 was a fellow named Bear Bryant, who, within the week, resigned from Texas A&M to return home to Alabama.

During the 1958 season, writers used "three yards and a cloud of dust" when referring to Split T and Southwest Conference teams generally and South Carolina and Ohio State specifically. Similar comments appeared about cloud dusters other than Ohio State during the 1959 season. Still, the expression was overwhelmingly applied to Ohio State after Woody Hayes embraced the phrase when speaking at a 1959 coaching clinic:

… some newspapermen call our attack ‘three yards and a cloud of dust.' But we don't care what the offense is called as long as it wins football games. I'm willing to take three and one-third yards on every play and force the other guy to make mistakes.

Associated Press, ‘Hayes Talks At Clinic,’ Herald-News (Passaic, NJ), March 17, 1959.

Woody's embrace of power football and contempt for sportswriters forever linked the expression to his version of Ohio State football. Whether used in praise or criticism, Hayes' position as a dominant force in the Big Ten and college football generally fortified the link. Now, one is seldom mentioned without the other.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.