Terminology... X's and O's

This is article #3 in a series covering the origins of football’s terminology. All are available under the Terminology tab above. My book, Hut! Hut! Hike! describes the emergence of more than 400 football terms.

While it is unclear who first diagrammed a football play, we know that Princeton captain Edgar Allen Poe (the writer's second cousin, twice removed) used checkers to illustrate plays to his teammates in 1889. The newspaper reporter who told that story included two play diagrams in the article, using circles (or the letter O) for the offense and shaded circles for the defense.

Stagg and Williams also used circles in their 1893 book that included sixty-nine play diagrams, though they shaded the offense rather than the defense. Camp and Deland's 1896 Football used little figures, while Pop Warner used little figures or empty circles, depending on the book.

Relative to other coaches of his era, Bob Zuppke’s play diagrams in his 1924 Football, Technique and Tactics were information-rich. He used circles on both sides of the ball but distinguished the defense with small shaded circles inside the standard circle. More important, he highlighted the offensive players differentially based on whether they carried the ball or performed other actions.

So, for books published before 1930 and in hundreds of period newspaper articles, coaches overwhelmingly represented both the offense and the defense using circles. Despite the use of circles in most play designs, X's and O's became a shorthand expression for the details of football techniques, play design, and strategy.

Of course, there is always that guy; in this case, it was Army's Charles Daly. Daly used X's for the offense and O's for the defense in his 1919 American Football and since football's X's and O's expression first appeared in 1927, Daly might have fathered the term, but there is no evidence that he did.

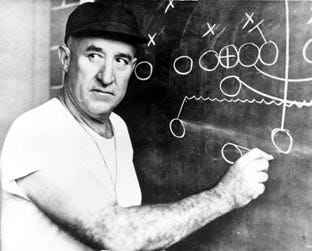

The expression more likely comes from coaches using X's and O's when drawing plays informally, such as on a chalkboard during team meetings: sports reporters picked up on the technique, commented on it, and the expression caught on, but who knows?

Zuppke's approach of shading offensive players based on their actions proved beneficial and was adopted by others, as seen in Bernie Bierman's 1937 Winning Football. By the time Bierman published his book, the diagramming game had advanced to labeling each offensive player with a number (numbers made sense given the unbalanced lines of the time) and giving the center both a crosshatch and a number (8). In addition, he shaded the ball carrier and represented the defense with boxes, labeling them by their single-platoon position.

Coaches soon dispensed with the boxes for defensive players, showing them only by letter designation. Later, two-platoon football and increased defensive complexity led to labeling the defensive positions based on the strong and weak side, field and boundary, and other terminology.

In the end, it is unclear why football's nuts and bolts became known as the X's and O's. Since teams of the 1920s and 1930s concentrated on offensive play design, we probably should call them football’s O's and X's, but that is not how it worked out, so X's and O's it is. Nevertheless, the symbols used to represent the players, their movements, and other aspects of football plays have come a long way, and Edgar Allen Poe's checkers are nevermore.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.