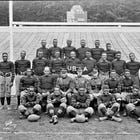

Adolph Hamblin And The 1935 West Virginia State Yellowjackets

There is little written about HBCU football before the 1960s, and I have not contributed much either. Their stories do not appear in the mainstream publications I frequent, so I don’t stumble across their stories as I do those related to Yale, Texas, or Stanford. I have written extensively about the West Point Cavalry Detachment football teams of the late 1920s and early 1930s, teams comprised of Buffalo soldiers, or Black enlisted men stationed at West Point. I told their tale in a story and additional research, linked below and found under the Teams tab above. But, that’s about it.

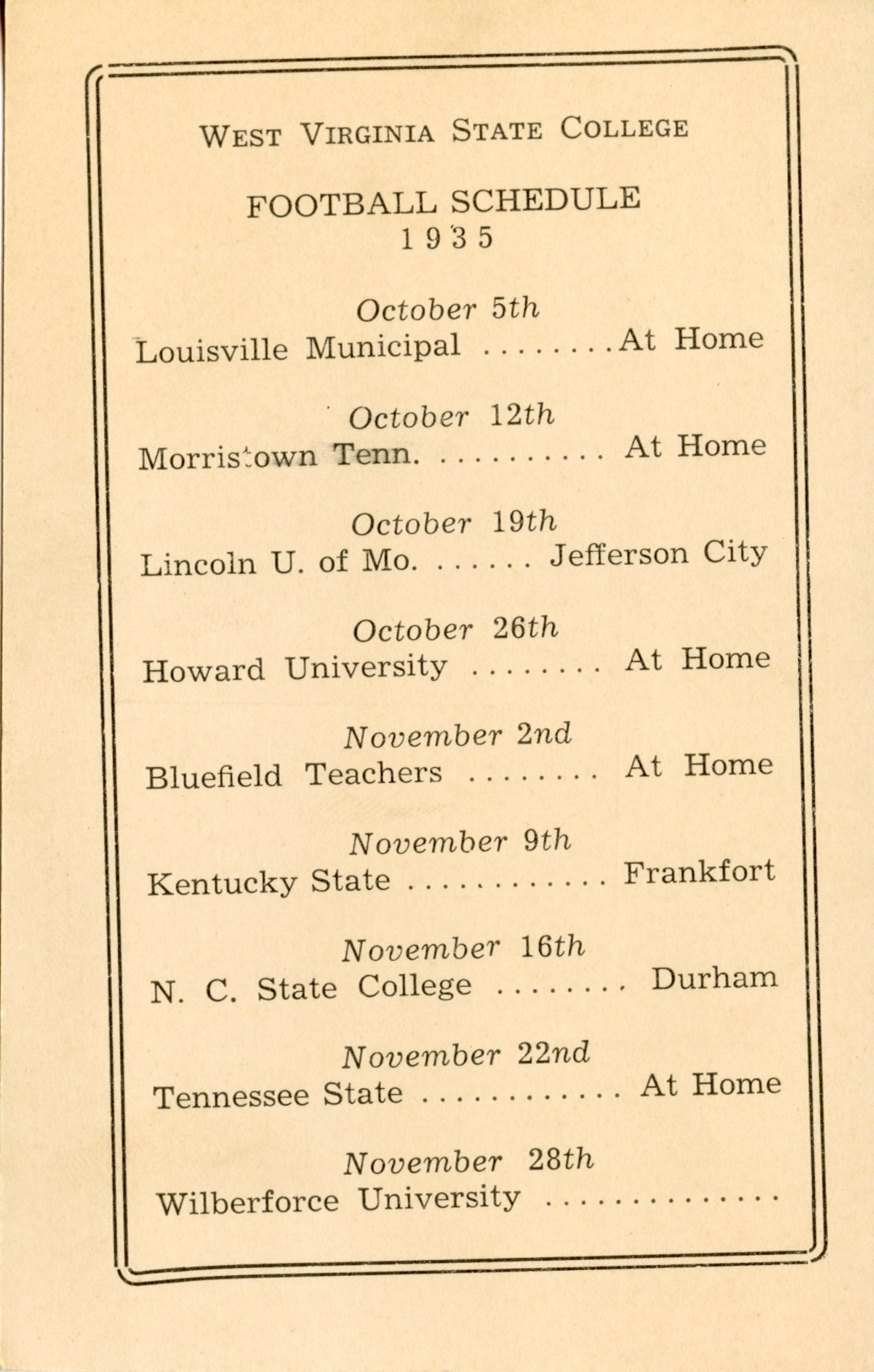

So, when I recently came across a 1935 West Virginia State football schedule postcard, it sent me down a path taken infrequently. West Virginia State (WVSU) is one of the original 19 land-grant colleges. Although the student body is now predominantly White, it began in 1891 as the West Virginia Colored Institute. In 1935, their opponents were HBCUs, as seen on the schedule below.

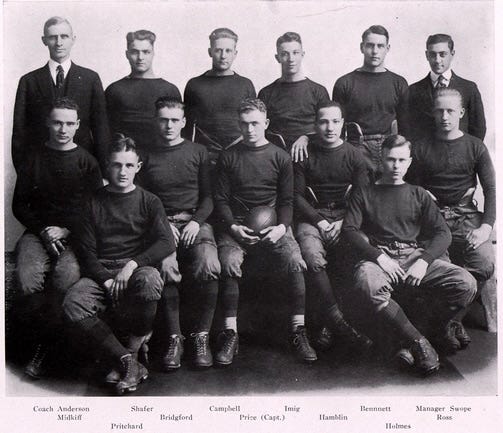

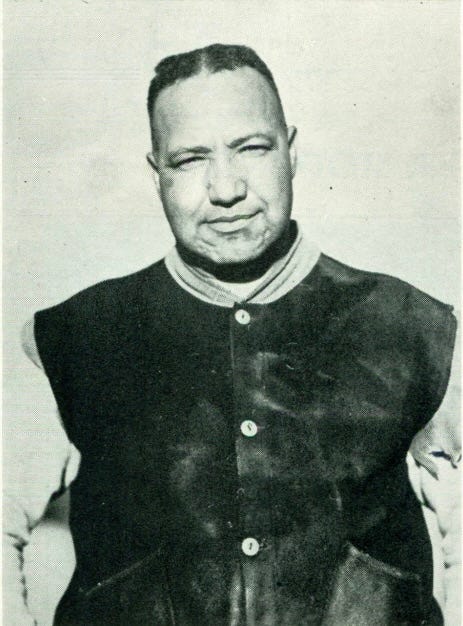

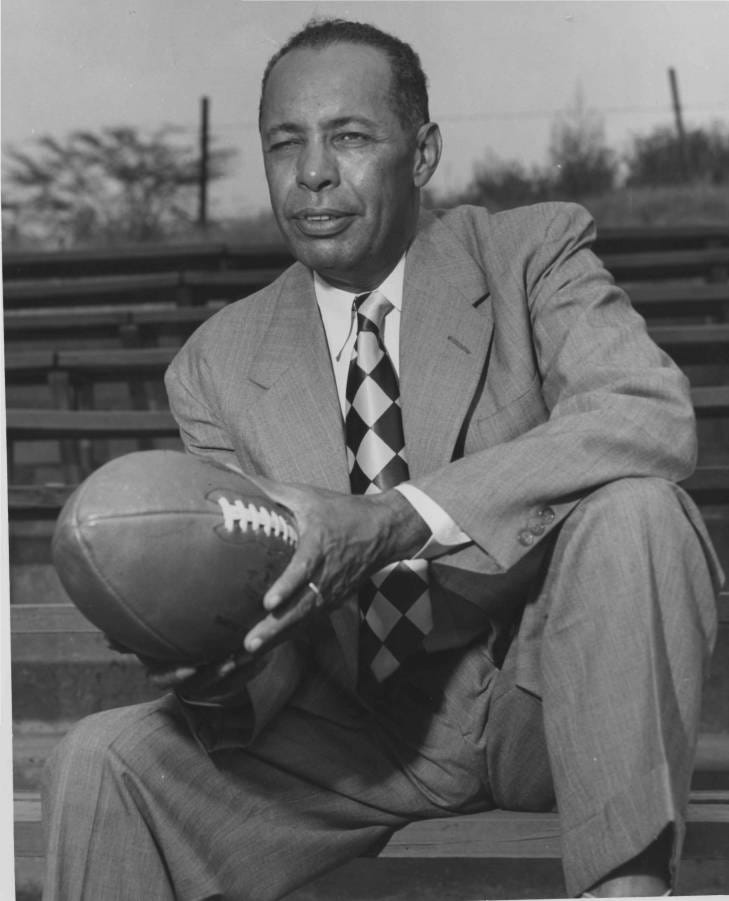

According to the 1923 yearbook, WVSU football began in 1901 and struggled to find the resources to equip and coach the team, as well as to travel to other HBCUs, few of which were nearby. Their fortunes began to change in 1921 when they hired Adolph “Ziggy” Hamblin, who played for Knox College in his hometown, earning 16 letters, captaining multiple teams, serving a stint in the Army from 1918 to 1919, and remaining for one year after graduation to serve as a biology instructor and assistant coach.

Hamblin coached football at WVSU from 1921 to 1945, often serving as coach for the basketball and baseball teams, and chairing the Biology Department. He was a busy fella.

Unfortunately, even West Virginia State’s athletic department does not have year-to-year records for Hamblin’s early years. However, his 1922 team apparently took on and defeated some nationally prominent teams, with some authorities naming WVSU as the black national champions. While we can assume he fielded some strong teams, he was unable to beat Wilberforce University in Ohio from the time he arrived through the 1934 season, despite playing them every year.

Still, Hamblin had the makings of a strong but young team in 1935. His Yellowjackets opened the season at home, facing Louisville Municipal College, a school formed when the city’s Black residents refused to vote for a tax increase to fund the University of Louisville, since the school did not allow them to enroll. Louisville Municipal became a “separate and equal” college, with a portion of the city’s taxes allocated to it, until it closed in 1951. WVSU dominated Louisville’s finest that day, walking away with a 37-7 victory.

Next up was Morristown College of Tennessee, coached by a former WVSU player, Hunter N. Johnson, who was in his first year in Morristown. Despite Hamlin coaching against a former player and Morristown leaving it all on the field, WVSU scored at will, once scoring on three successive offensive plays, and walking away with a 122-0 win.

Things got tougher the following week during the Yellowjackets’ trip to Jefferson City, Missouri, to take on Lincoln University.

After three scoreless quarters, the back-and-forth battle turned in the fourth stanza as Lincoln blocked two WVSU punts, turning both into touchdowns, and sending Lincoln’s Homecoming crowd into the night with a 14-0 victory.

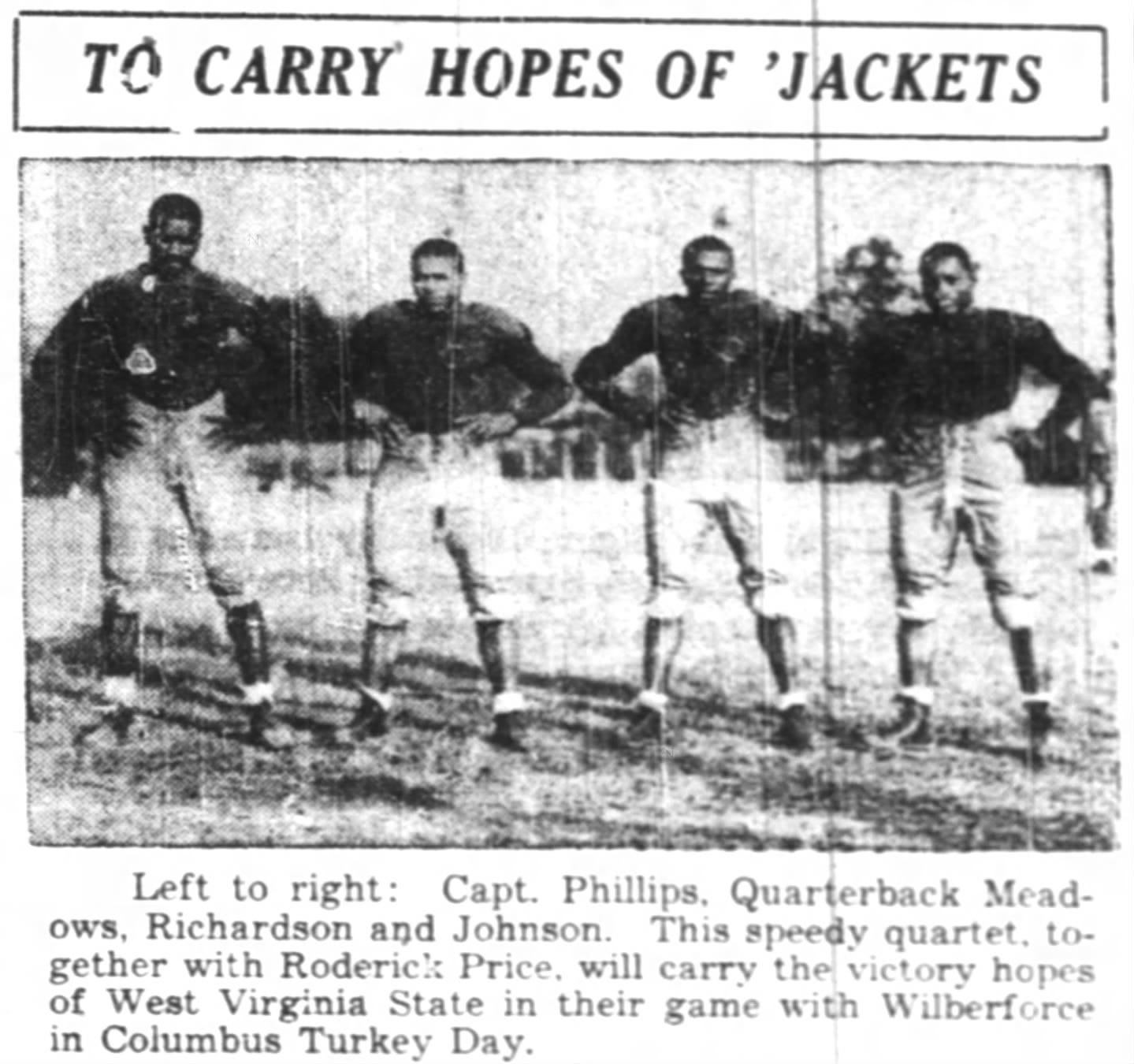

Next came a home game with the Howard Bison, in a series tied at 6-6-4. The herd lacked thunder that year, and the Yellowjackets’ quarterback, Floyd Meadows, ran for two touchdowns and threw for another as WVSU silenced the herd, 38-6. Intrastate-rival Bluefield State was next on the docket, and with Meadows contributing two more touchdowns, as the Yellowjackets took their record to 4-1 by besting the Big Blue, 20-12.

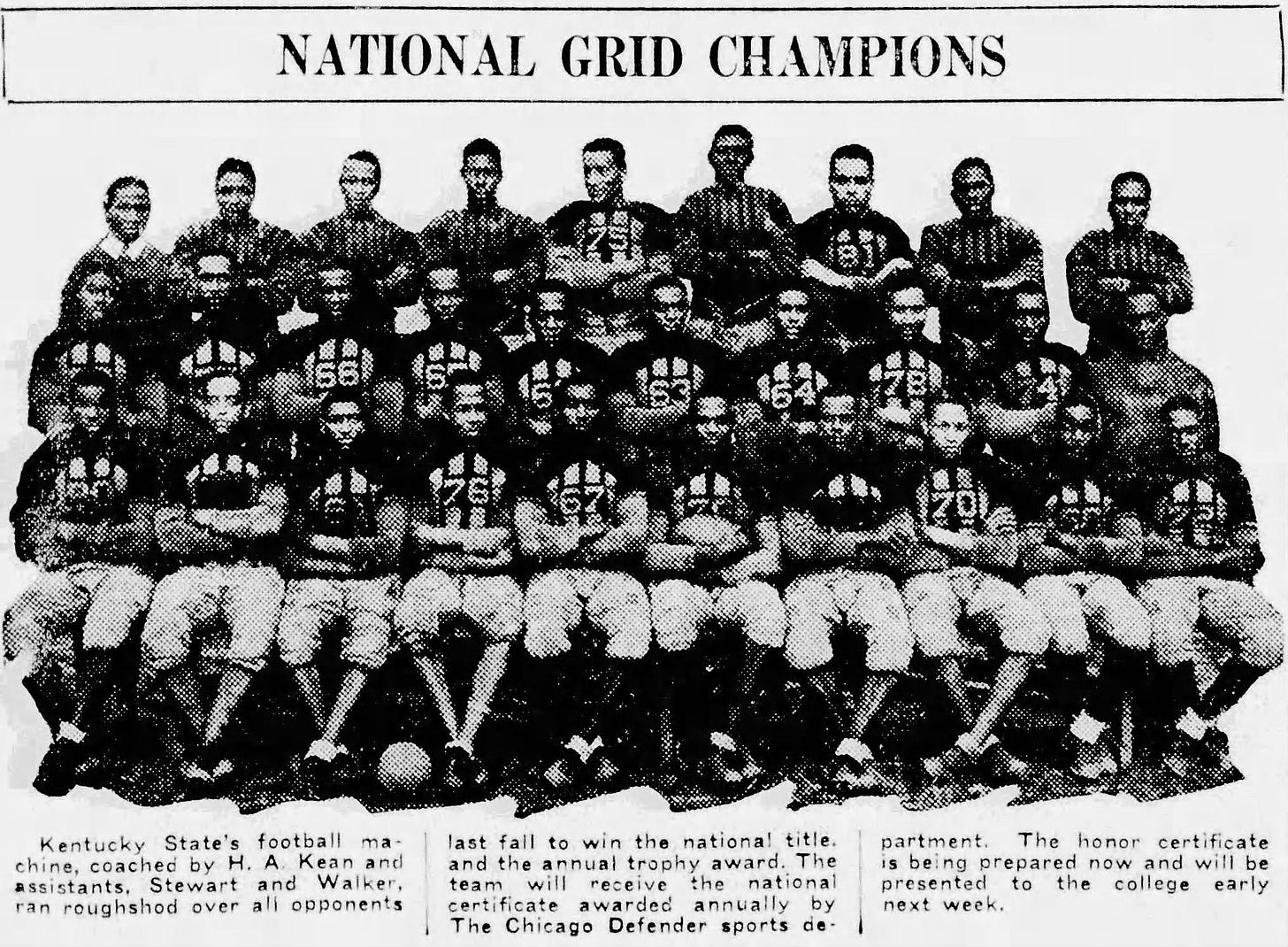

An away game with the two-time defending Black national champion Kentucky State Thorobreds loomed.

Coached by Henry Kean, who won two national titles at Kentucky State, four at Tennessee State, and compiled a 165-34-9 record (83% winning percentage), the Yellowjackets were up against it, giving up first-quarter and third-quarter touchdowns in the 13-0 loss.

The Yellowjackets spent the next two weeks regaining their winning attitude by downing North Carolina A&T, 46-6, and Tennessee State, 33-0. That set up their end-of-season contest with Wilberforce of Ohio, a team that had given up 3 points all year. The last three WVSU-Wilberforce games had been played in Chicago, Detroit, and Cincinnati. While the location was undecided when WVSU printed their schedule, they slated this one for Columbus.

Honored guests at the Thanksgiving Day game included the governors of West Virginia and Ohio, and, more important, Joe Louis, who agreed to come down from Detroit. All was in readiness for the game, with every attendee looking their best to support their team.

Once again, special teams hurt the Jackets as a blocked punt set up the first Wilberforce touchdown. WVSU responded quickly thereafter by blocking a Wilberforce punt, scoring, and when Wilberforce chose to kick to WVSU, Meadows ran it back for a touchdown, taking a 13-7 lead. A fourth-quarter Wilberforce tally gave the bad guys a 14-13 lead, but WVSU came back and drove the ball to the two-yard line with seconds remaining. Unfortunately, the gun sounded, and Wilberforce left victorious once again.

If things did not go WVSU’s way in 1935, the tide turned in 1936 as the Yellowjackets buzzed through every opponent until the season finale with Wilberforce. That time, the game ended in a 6-6 tie, but the Jackets had shown enough to be named Black national champions, a title they shared with Virginia State.

Regardless of their talents and interests, none of the players or coaches involved with the HBCU teams of the era were welcome in the NFL, and only a handful of Black players appeared on Big Ten, Pacific Coast Conference, or other rosters. Like many other racial injustices, their exclusion is a stain on the American fabric we cannot remove and should never forget or sweep aside, as some who wave the flag would prefer. Like many of their players, Adolph Hamblin and Henry Keane had the talent to succeed at any level. Ironically, their HBCU players and communities reaped the benefits of their coaches’ never having the full opportunity they deserved.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books, donate, or otherwise support the site.

Check out When Football Came To Pass, released earlier this week.