Armistice Day Football: An American Tradition

World War I ended at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918. In the years that followed, battles between football elevens were central to America's commemoration of The Great War. Armistice Day was celebrated on a small scale in 1919 before exploding in popularity through the 1920s and becoming a national holiday in 1938.

The importance of Armistice Day games varied at each of football's levels. Armistice Day games never became significant among the nation's colleges. Most continued playing on Saturdays and only touted Armistice Day in those years November 11 fell on a Saturday, as it did in 1922. Perhaps a few dozen colleges regularly scheduled games on November 11 when it fell on other days of the week, but those were seldom football powers. Likewise, the emerging professional leagues stuck to their Sunday schedules because many players held full-time jobs in other cities and were unable to travel for mid-week games.

Armistice Day's more significant role fell to high school teams and those with military ties. With the Great War fresh in everyone's minds, cities and towns across the country held parades and other celebrations to mark the day. High school football games, often with rival high schools, capped the well-attended local celebrations. In the days before commercial radio and television, high school, small college, and other local sporting events earned sizable attendance numbers, unlike the situation today.

Armistice Day games with a military association came in two flavors that reflected football's organization in the military during the war. America's WWI military training camps had extensive intramural football leagues and the more well-known "varsity" teams that played other training camps and colleges. Both football forms helped fuel pro football's popularity after the war, particularly among the majority of service members that never attended a college or university.

The intramural leagues in the military camps spurred the formation of football teams at the many American Legion posts then popping up across the country. Formed in March 1919 and comprised of those who served during WWI, the American Legion grew into a significant political force supporting veterans' issues. Still, it delivered much of its value at the local level, including recreational activities. American Legion football teams played one another, small colleges, industrial teams, and quite often, local high schools. American Legion games were popular in the years immediately following the war but gave way to high school games as the youthful veterans aged.

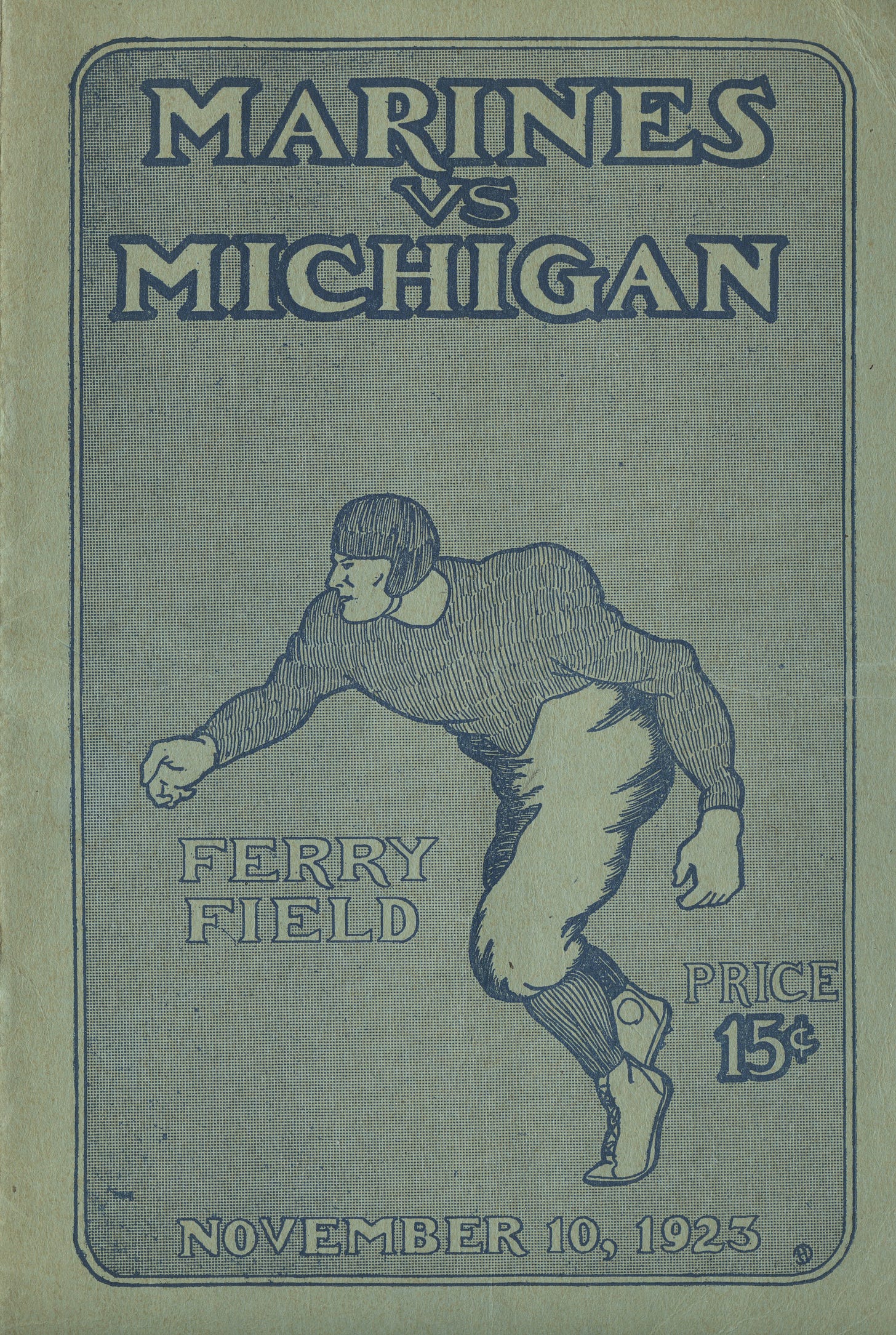

The 'varsity' level of competition in the active military also faded after the war. As men mustered out of the service, only a limited number of camps played outside competition or, more accurately, played them competitively. Great Lakes Naval Training Station and the Mare Island Marines were among the nation's top football teams in 1918, playing one another in the 1919 Rose Bowl, but each quickly fell from the competitive ranks. Great Lakes was marooned in their 1919 season opener, losing 123-0 to Chicago, while the Mare Island Marines opened the 1920 season with an 88-0 loss to California. Only the famous Quantico Marines teams of the 1920s consistently matched up with major college teams. The San Diego Marines teams took their place in 930.

In the post-war days, most camps and ships played one another in district leagues, with some being early season fodder for major colleges. The military also formed regional all-star teams on each coast that faced college teams and played for all-service championships at season's end.

The East Coast service championship, known as the President's Cup after Calvin Coolidge donated the same in 1925, attracted large crowds, often counting the President and members of the Cabinet and Congress among the spectators. However, the game was typically played in late November and was not associated with Armistice Day.

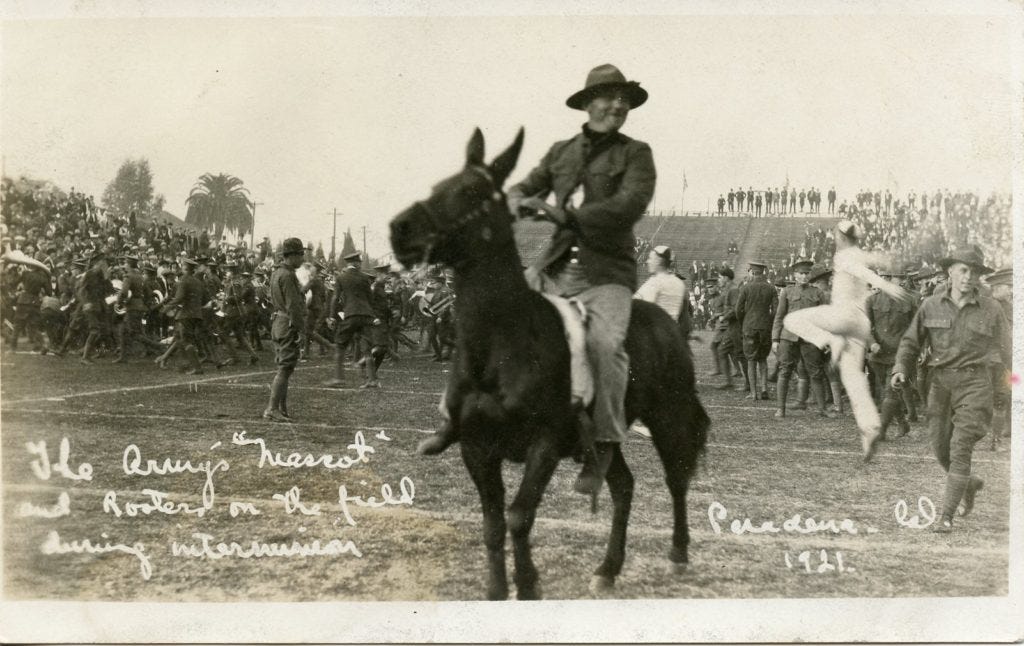

The West Coast, on the other hand, embraced Armistice Day as the point in the calendar to settle questions of interservice football prowess. The first game came in 1920 at Tournament Park in Pasadena. (Tournament Park hosted the eight Rose Bowls played before the construction of Rose Bowl Stadium. Only after the stadium opened was the game referred to as the Rose Bowl, and it was not until the mid-thirties after the Orange, Cotton, and Sugar Bowls came along that postseason games became known as "bowl" games.) March Field, which hosted aviation training squadrons with limited numbers of men, represented the Army in the 1920 game, while the Navy put forward its all-star Pacific Fleet team and its convoy of former college football players. Navy dropped its anchor on Army that day, winning 124-0. The game was not as close as the score suggests, with Army gaining only one first down.

Army wised up in 1921 and had their all-star Ninth Army Corps team met the Pacific Fleet sailors. Army lost in 1921 as well -by 100 fewer points than they had in 1920- to begin a twenty-year tradition of competitive games between the services.

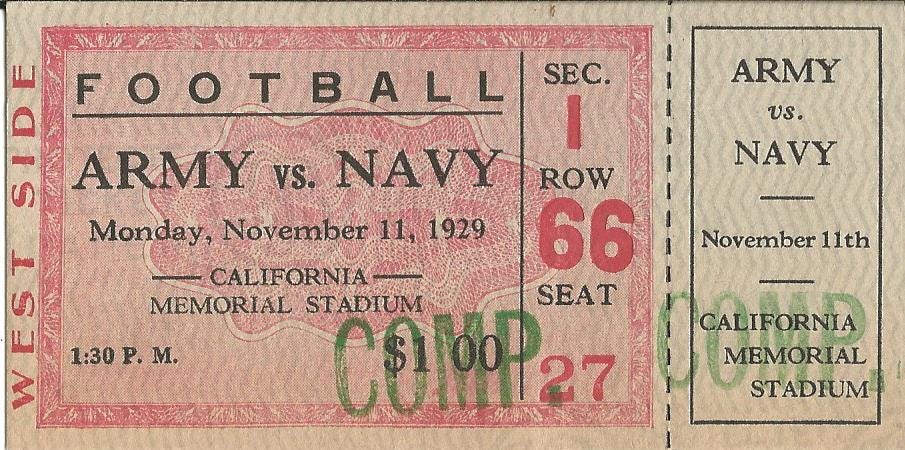

The Armistice Day game became the premier athletic event on the West Coast military social calendar, bringing an enthusiasm similar to the Army-Navy game played by the academies. The game shifted to California's Memorial Stadium in 1926, regularly drawing crowds of 60,000 and more. It remained in Berkeley until 1941, but WWII interrupted the series, and it did not renew following V-J Day.

More broadly, the traditions honoring the sacrifices made during WWI faded in importance after WWII. As the nation began shifting from Armistice Day to Veterans Day celebrations, a transition signed into law in 1954. Service football, which was highly competitive during WWII, all but disappeared following WWII. High school Armistice Day games faded as well as an increasing number of states initiated championship tournaments, making the scheduling of Armistice Day games untenable. High school games on Armistice Day were played in the thousands in the twenties, in the hundreds in the fifties, and in the dozens in the eighties before disappearing altogether. Games that once captured the imagination of local and broader communities are now only a distant memory.

Click here for options on how to support this site beyond a free subscription.