Big Boys on the Run: When Linemen Carried The Ball

Football of the 1890s and early 1900s deserves criticism for its violence, but they did one thing right back then, their linemen toted the rock. Unfortunately, the onset of the passing game, player specialization, and rules to simplify officiating have dimmed a once glorious element of football. Given this injustice, it is time to examine selected points in the game's history when football's formations and plays put the ball into the hands of its noble linemen.

Rugby's free-flowing nature ensures their biggest guys carry the ball on occasion. That was also the case in football's early days when its rules overlapped rugby's, and it remained so as football shifted to regimented plays run from the Traditional T, Guards Back, and Tackles Back formations.

Regardless of the formation, every team had plays in which their guards, tackles, and ends carried the ball by design. For example, George Woodruff, who devised the Guards Back formation at Penn, regularly ran guard sweeps (aka guard arounds). Similarly, Pop Warner, who played left guard at Cornell, claimed he designed a guard around play allowing him to carry the ball against Williams in 1893. His misdirection play had the four backs run wide left while Warner took the handoff and headed right, gaining solid yardage until fumbling on the only carry of his career. Warner's run to the left without blockers presaged the bootleg he pioneered while coaching Stanford in 1927. His Stanford team also gained forty yards on one of several guard around plays in the 1928 Rose Bowl.

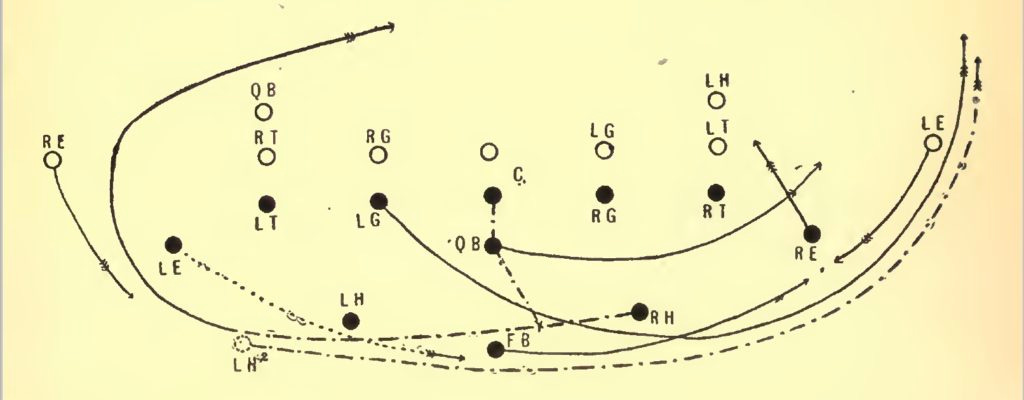

Amos Alonzo Stagg and Henry. L. Williams' seminal 1893 book, Treatise on American Football, includes diagrams and instructions for sixty-nine running plays, twenty-one of which put the ball in the hands of guards, tackles, or ends. The guard around shown below is an early example of the play that remained in use as late as the 1950s.

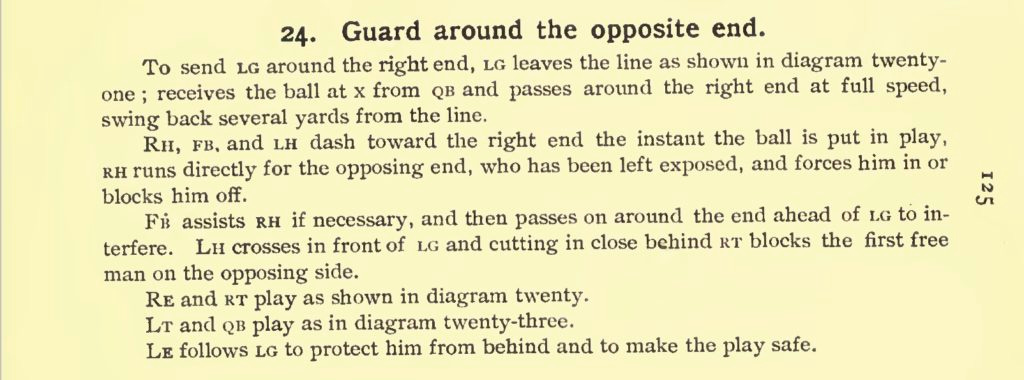

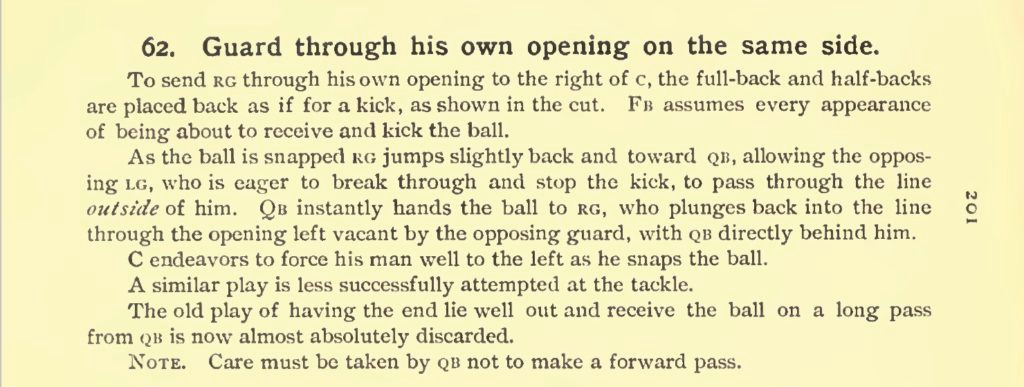

Like the fake punt below, some of Stagg and Williams' plays appear harebrained through 21st-century eyes, yet they also demonstrate that some principles transcend time and rule changes. The offense aligns in punt formation, with the ball snapped to the quarterback, who normally lateraled to the fullback/punter in the days before teams long-snapped to the punter. As the quarterback receives the snap, the right offensive guard allows the defensive guard to take an outside route to the punter, and then takes the handoff from he QB, and runs through the hole left by the defensive guard. Odd as the play may seem, the same deception appears several decades later when screen passes and draw plays entered the game.

Similarly, George H. Brooke, a prominent coach, and widely published newspaper columnist, commonly offered "how to" instructions on football. Among his 1905 articles, he outlined eighteen running plays fundamental to any offense. The halfback carried the ball on six plays, the fullback handled another six, while the guards, tackles, and ends each received the ball on two plays. Thus, a prominent coach of the pre-forward pass era thought offenses should have linemen carrying the ball on one-third of their plays. From that point, however, football increasingly took the ball from the hands of its interior linemen. Let's review how this occurred for each position.

The primary play for the game's snappers was the center rush. Under the rules of the day, players could run with the ball only after another player took possession of the ball from the center. For the center to legally run with the ball, he snapped to the quarterback, who quickly gave the ball back to the center before the snapper ran like hell. However, since it was difficult for the officials to judge whether the quarterback possessed the ball, they changed the rules to allow the center to receive a handoff only after turning 180 degrees from his snapping position and taking the ball from at least one yard behind the line of scrimmage.

While the new rule effectively eliminated the center rush, some coaches ran the play the old-fashioned way; they cheated. Especially at the high school level, coaches assumed the officials would not understand the rules or be afraid to rule on an exchange they had not seen clearly. Though illegal, the center rush still makes an occasional appearance and remains legal in certain six-man or other limited player levels.

Moving on from centers and turning our attention to guards, those big boys got the ball on guard around plays after 1905, though doing so required increased ingenuity. One approach had the center "snap" the ball but not release it as he extended his arm between his legs. Meanwhile, the quarterback faked like he had the ball and ran to the right while the right guard turned, took the ball from the center, and ran around the left end. Despite the play's cleverness, the rule-makers of 1931 barred the player next to the center from receiving the snap and extended the ban to the tackles a few years later.

Likewise, the rule-makers extended the requirement to make a 180-degree turn and receive the ball one or more yards behind the line of scrimmage to all linemen receiving a forward handoff. This rule made guard around plays slower. When combined with the Modern T formation and liberalized passing rules, teams opted to give the ball to their "skill players" rather than have linemen run the ball.

Still, some coaches retained a soft spot for the guard around play, and they recognized the restrictions on forward handoffs did not apply to linemen advancing fumbles. So, borrowing from the "settin' hen" play Tennessee and Vanderbilt ran in the 1930s, they had the quarterback intentionally fumble the ball behind the center before faking a sweep to the right. In the meantime, the right guard pulled left, picked up the fumbled ball, and scurried around left end. Most now know the play as the "fumblerooski," after Tom Osborne's Nebraska teams ran it several times, most notably when #1 Nebraska met #5 Miami in the 1984 Orange Bowl.

As with earlier plays that put the ball in the big boys' mitts, the fumblerooski made life difficult for the officials, so the rule-makers banned intentional fumbles in the vicinity of the snap in 1993. However, the NFL only banned intentional forward fumbles, so the fumblerooski remains legal in the pros when the quarterback fumbles the ball backward.

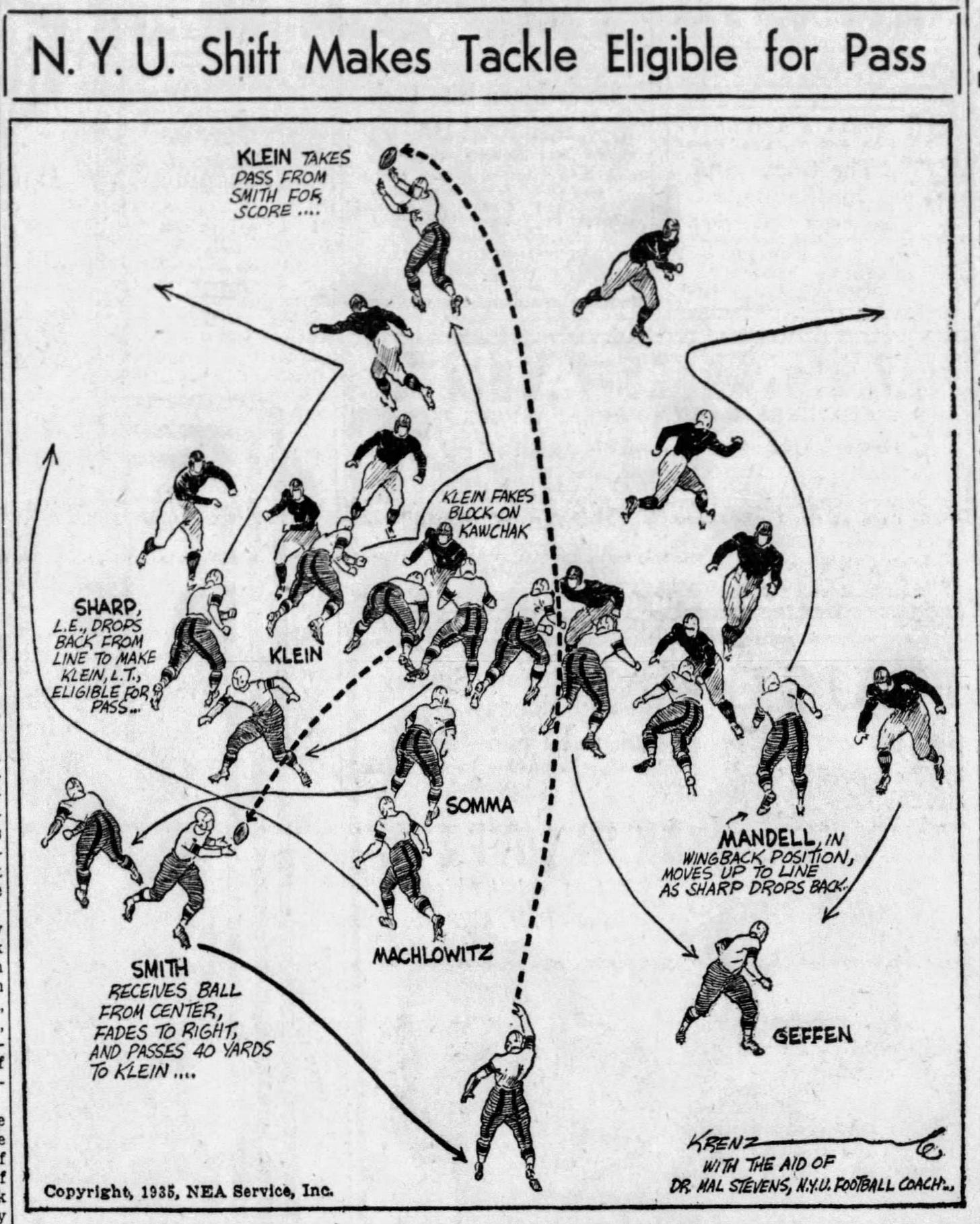

Unlike the other line positions whose moments of glory came via running plays, tackles earned their fame in the passing game. The 1906 rules legalizing the forward pass defined as eligible receivers the offensive backfield and the outermost player on either end of the line of scrimmage, usually the offensive ends. Of course, tackles or other positions could become eligible given specific alignments and shifts, and tackle-eligible plays quickly entered the game. Teams typically ran the tackle eligible from conventional formations, but others experimented with spread or punt formations akin to the A-11 offense that came onto the football scene in 2007. The early formations had the center align over the ball with the quarterback five or more yards deep, and the other nine players spread across the field and behind the line of scrimmage. Just before the snap, some players shifted to ensure the offense had seven players on the line of scrimmage. These late movements made it difficult for defenses and the officials to know which players were eligible receivers, particularly since ineligible receivers were allowed downfield on all pass plays until 1939.

Unfortunately, the formations and movements were viewed as trickery rather than fundamental football, so a new set of rules approved in 1915 required at least three backfield players to be five or more yards behind the line of scrimmage at the snap, effectively eliminating late shifts and these spread formations.

Tackle-eligible plays reemerged when offenses began splitting one or both ends since defenses had difficulty judging whether the split end or tackle was the outermost player on the line of scrimmage. But, once again, the football gods considered this a form of trickery, so the NFL declared players wearing numbers 50 through 79 to be ineligible in the early 1950s. The NCAA did the same in 1955, reversing their decision in 1956 due to pressure from coaches like Bear Bryant, but even the Bear could not hold back the tide, and the NCAA reinstituted the ban in 1967.

Today, NFL players wearing ineligible numbers can declare their eligibility to the referee before plays, though declaring players typically align as tight ends. Strictly speaking, these are not tackle-eligible plays, but they provide one of the few opportunities to get the ball in the hands of big boys. College players wearing ineligible numbers cannot declare themselves eligible, so they are limited to catching the occasional backward pass. While backward passes look and feel like some forward passes, they count as rushing yards in the game statistics.

As shown above, each step taken to limit the ability of linemen to carry the ball proved difficult for officials to enforce, leading to greater restrictions until the game reached the point that linemen were effectively barred from carrying the ball. Player and coach specialization has reinforced the distinction between linemen and "skilled" positions making it unlikely that ball-toting big boys will return without a fundamental restructuring of the game. A final comment is that coaches have exploited the game's rules to their advantage since the game began, and the fumblerooski is a prime example of that tendency. The sequence of rule changes needed to stop linemen from running with the ball illustrates why the 2021 NCAA rules book runs 236 pages.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.