Bleacher Collapses and Other Stadium Tragedies

College football fans entering stadiums today worry about many things. They fret about the game's outcome and whether the alcohol they consumed before entering the stadium will see them through the contest. Surely, the least of their worries is the structural integrity of the stadium in which they will spend the next several hours. However, there was a time when poor design, lax maintenance, low-quality materials, and other factors made the stadiums and surrounding structures a threat to fans' life and limb.

Early football games were played on open fields and college greens. As teams increasingly looked for fans to subsidize their equipment and travel expenses, the playing fields were roped off or moved to polo grounds, baseball stadiums, and other enclosed spaces, almost all built of wood. The wooden structures were often built of untreated lumber, making their maintenance expensive and easily skipped in years ticket sales tailed off. Even more problematic, college football's increased popularity meant that many stadiums lacked the capacity to handle the crowds seeking access to the biggest games on the schedule. For big games, the permanent stands were supplemented by temporary bleachers that brought any number of problems.

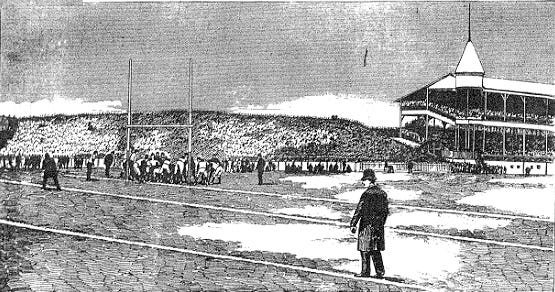

The earliest bleacher collapse of note occurred at the 1890 Yale-Princeton game at Eastern Park in Brooklyn. The Thanksgiving Day game was a top contest that year, featuring six All America players, including Yale's Pudge Heffelfinger. Pudge became football's first professional player two years later when he accepted $500 to play a game with the Allegheny Athletic Club.

Eastern Park was home to the Brooklyn Wonders of the professional baseball Players League, but expectations for a large crowd led to the building of 4,000-seat temporary bleachers standing twenty feet tall. As the public filed into the stadium during the pre-game festivities, the temporary bleachers collapsed, throwing an estimated 2,000 fans to the ground. The fifty injuries included broken bones, crushed limbs, and concussions, with all the victims surviving their injuries.

Similarly, the crowd expected to gather for the 1897 Cal-Stanford game at Recreation Park in San Francisco's Mission District led to the building of temporary stands topped by a temporary roof. During the game, some boys and young men in the standing-room-only (SRO) crowd found a better view of the game atop the temporary roof. An exciting play late in the game caused a movement among the rooftop dwellers, leading to the roof and its inhabitants falling onto fans below. Nearby fans assisted the injured, though some were robbed of their valuables by pickpockets posing as rescuers.

The deadliest event for spectators in American sports history came three years later when Cal and Stanford again met at Recreation Park. This time, the tragedy did not involved collapsing bleachers, but the roof of a newly-built glass factory that loomed over the north end of the field. The more-than-capacity crowd meant many local youths and some adults could not get into Recreation Park, so hundreds climbed atop the factory roof. Unbeknownst to them, the factory was set to open the following Monday and its furnaces were warming to the 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit required for production. The roof, built to ventilate the factory and not support additional weight, collapsed twenty minutes into the game. Many fell fifty feet to the factory floor, while others spilled onto the hot furnace and burned to death. Those inside the Park were unaware of the mayhem and the game carried on as normal. Twenty-three perished from injuries suffered that day.

The 1902 Wisconsin at Chicago game saw temporary circus bleachers, assembled the night before the game, collapse shortly after play started, leaving forty injured. Three years later, Wisconsin visited Michigan's Ferry Field, where platforms for the SRO crowd collapsed behind the bleachers, wounding twelve.

The specter of death accompanied Colgate's 1906 visit to Syracuse and their game at New Star Park, a minor league baseball stadium that had opened a few years earlier. Syracuse was already building Archbold Stadium, which, following Harvard Stadium and Franklin Field, became the nation's third stadium built of concrete when it opened in 1907. These sturdier and safer concrete structures pre-saged those build during the college stadium boom of the 1920s. The 1906 game was the last between the rivals played in a wooden stadium. Early in the third quarter, a section of bleachers with boisterous Colgate rooters collapsed, resulting in one hundred injured and one death. As with similar events, the turmoil resulted in only a ten-minute delay. The starters remained in the game while the substitutes helped remove the debris.

One of the more disturbing incidents occurred as the captains completed the coin toss ceremony before the 1911 Mississippi-Mississippi State game, later known as the Egg Bowl. Played at the State Fair Grounds, which had a perfectly suitable, permanent grandstand on one side of the field, Mississippi's Athletic Association opted to build temporary stands on the opposite side and charge spectators 25 cents to sit there. Handling the contract to build the stands was the Ole Miss' football captain from 1910, who awarded the contract to his uncle. The latter built the stands in a soggy area, and the stands rose over standing water by game time. Luckily, there were only 1,500 attendees, so only 75 injuries resulted when the stands fell apart.

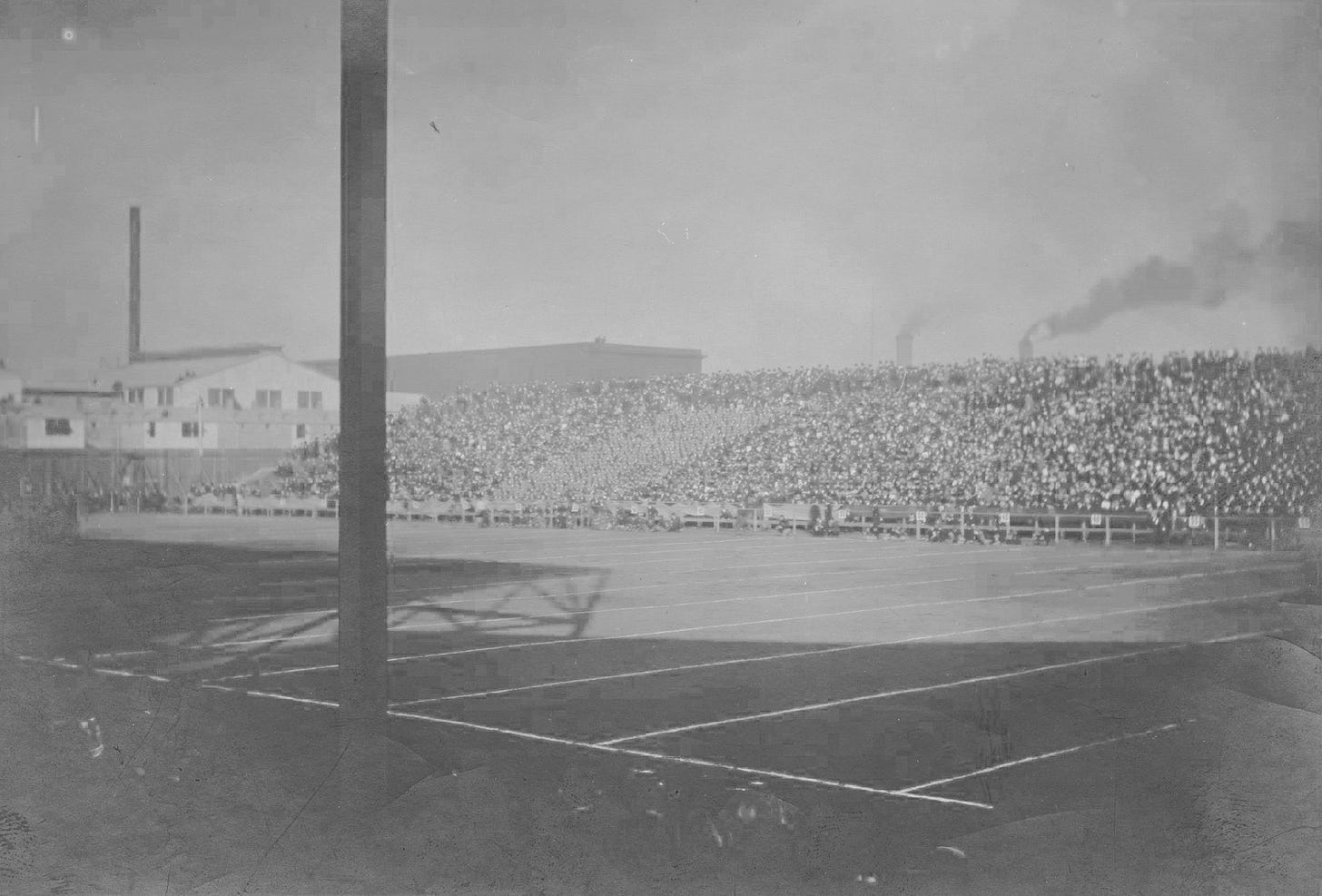

Similar collapses occurred at the 1913 DePauw-Rose Polytechnic game, the 1915 Wisconsin-Minnesota game, and the 1916 Akron-Wooster game. The events at Wisconsin are notable because it was the third time in fourteen years that some portion of the stands gave way at a Badger game. Camp Randall was partway through a renovation that season, so they erected temporary stands for their rival game. A section of those stands collapsed, injuring one hundred fans, and hastening the state legislature's funding the remaining renovation monies and providing for Camp Randall's first concrete stands. (The image atop the page shows the aftermath of the Camp Randall collapse. (The University of Wisconsin Collection.))

America's entry into World War I pulled tens of thousands of college men off college campuses, but the network of intramural and "varsity" teams at the military training camps exposed vast numbers to football, helping democratize the game and stoke its expansion post-war. The increased popularity of football in the 1920s led to colleges across the nation building massive new stadiums as memorials to their war dead. (Twenty-eight of today's sixty-four Power 5 teams play in stadiums built during the Roaring Twenties.) As important, the new stadiums were built of concrete and steel, virtually eliminating the incidence of collapsing bleachers. Temporary bleachers brought in for big games still caused occasional problems (see the 1940 SMU-Texas A&M game), but the rise of the new stadiums meant the fall of bleachers largely became a thing of the past and a forgotten element of college football's history.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.

Thanks for re-sharing this story today, I wasn't a subscriber when you first made it. One of the latest examples of permanent stands collapsing I've come across (though the search is admittedly not exhaustive) was at Richmond's Mayo Island Park / Tate Field, which had the stands collapse on 10/22/1927 while hosting a game between Maryland and VMI when the crowd stood up to cheer. Amazingly, no one perished, though 100+ injuries were reported. I mostly bring it up because the American Lumberman trade magazine wrote a pretty thorough investigation into what caused the failure. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015080321485&seq=528