Booklet Review: Walter Eckersall's How To Play Football

Those who study football history often point to seminal players who revolutionized or defined positions as the game evolved. Don Hutson was the first great split end, and Mike Ditka was the prototype tight end. Reggie White and Lawrence Taylor were the prototypes for their positions.

Other players were on the opposite side of the coin. They excelled at their positions, only to watch those roles fade or be redefined so that they no longer set the standard and were more easily forgotten as time passed. One example of the latter was Walter Eckersall.

He was the superstar quarterback immediately before and during the first year of the legal forward pass. He quarterbacked Chicago to a retrospective national championship in 1905 by beating Michigan 2-0 on Thanksgiving Day, with his punting being a critical factor in the win. He also quarterbacked them during the first year of the forward pass, but the quarterback's role in 1906 remained tied to the past rather than the pass.

He also is forgotten because he played at the University of Chicago. His school also dropped football 30 years after he played and almost a decade after he died, so rather than Chicago potentially maintaining its role as the Big Ten's private-school football power, as USC became further west, the tales of his exploits petered out for reasons other than time. When people stopped caring about UChicago football, they cared even less about its history, other than Stagg.

Eckersall remained a public figure as a sports reporter for the Chicago Tribune. Widely syndicated, readers nationwide knew his name and recalled his exploits. He was also a highly regarded football official, often traveling to games on the Chicago Tribune's dime while also refereeing the games he reported on. He was often on the field for top matchups, including several Rose Bowls when the Pasadena game was the only postseason game of note.

Given his place in football history, I recently acquired Eckersall's How to Play Football, a 32-page booklet published in 1928 by the Chicago Tribune and WGN, to see how Eckersall viewed the quarterback position 20+ years after he played his last.

Eckersall played before the forward pass and in its first year. In his day, quarterbacks called the play, aligned a yard behind or offset from the center, received the snap, and handed off or lateraled to a back, end, or tackle. By 1928, most teams operated from the Single Wing, Notre Dame Box, or similar formations. The quarterback remained the team's field general, a heady player who called the plays and then became a blocker.

As most coaches now employ the direct pass, center to ball carrier, the quarter back is used mostly as a running back. ...The quarter back should be able to run, kick or pass. He should be able to catch forward passes. If he is a field goal kicker, he adds strength to his team.

Eckersall was among the game's top punters and dropkickers of his era. He remained a fan of the punting game, and his view of punting was consistent with that of many coaches of the era.

After the ball is in play the field general should remember that his greatest offensive weapon is the punt. ...If the ball is in his own territory he should call for the punt on third down. If it is deep in his territory the ball should be booted on first down.

The exception to this approach came when punting into strong wind. In that case, the best strategy was to run a few plays, take time off the clock, and punt later in a set of downs.

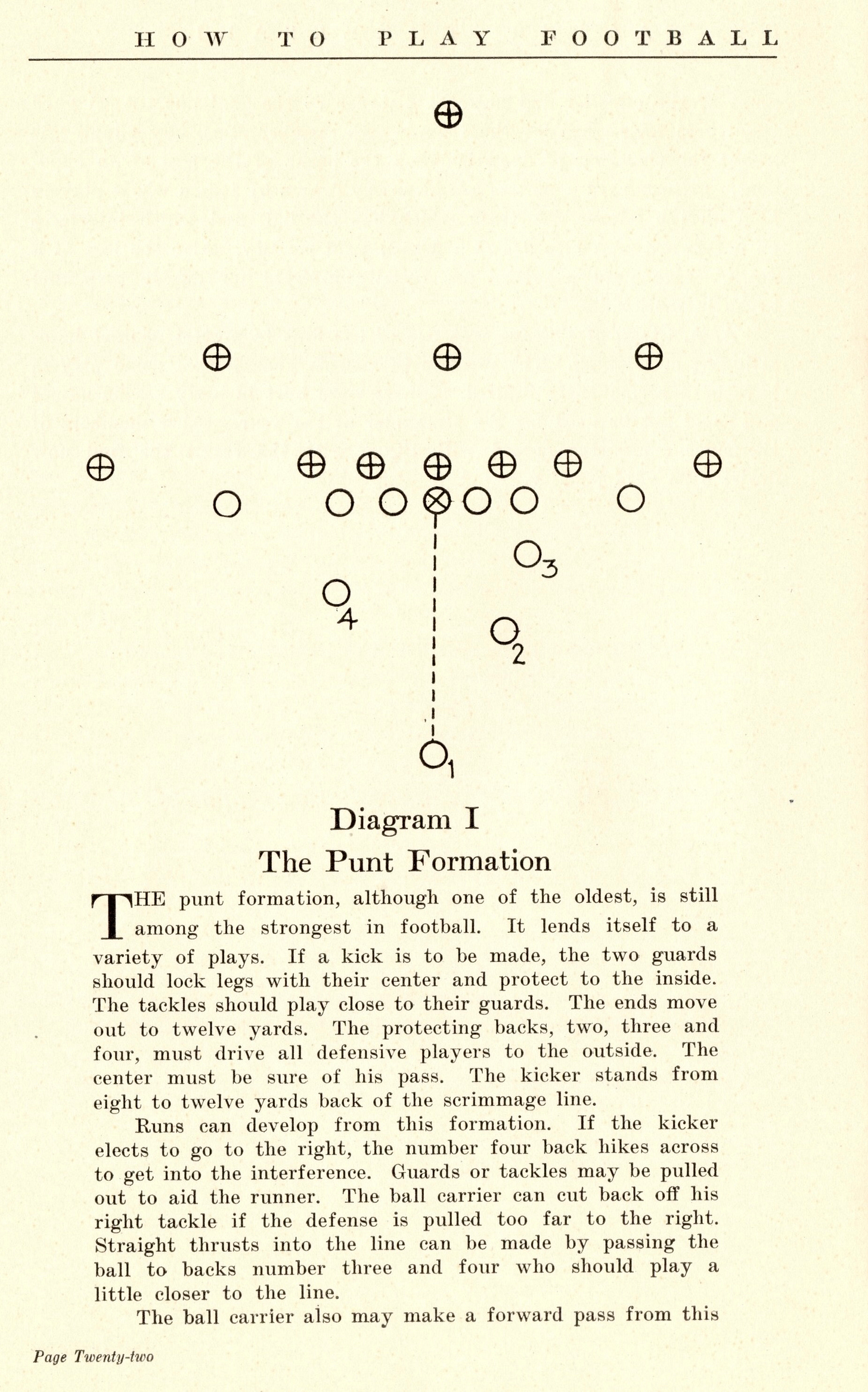

Quarterbacks remain the field generals today, though they display that role in their pre-snap reads, audibles, and RPO decisions. By 1928, the forward pass was accepted as a means of gaining ground, though it remained archaic compared to today. Teams often threw from the punt formation, ideally using a triple-threat back who could punt, pass, or run with the ball. Sometimes, that was the quarterback; other times, it was another back.

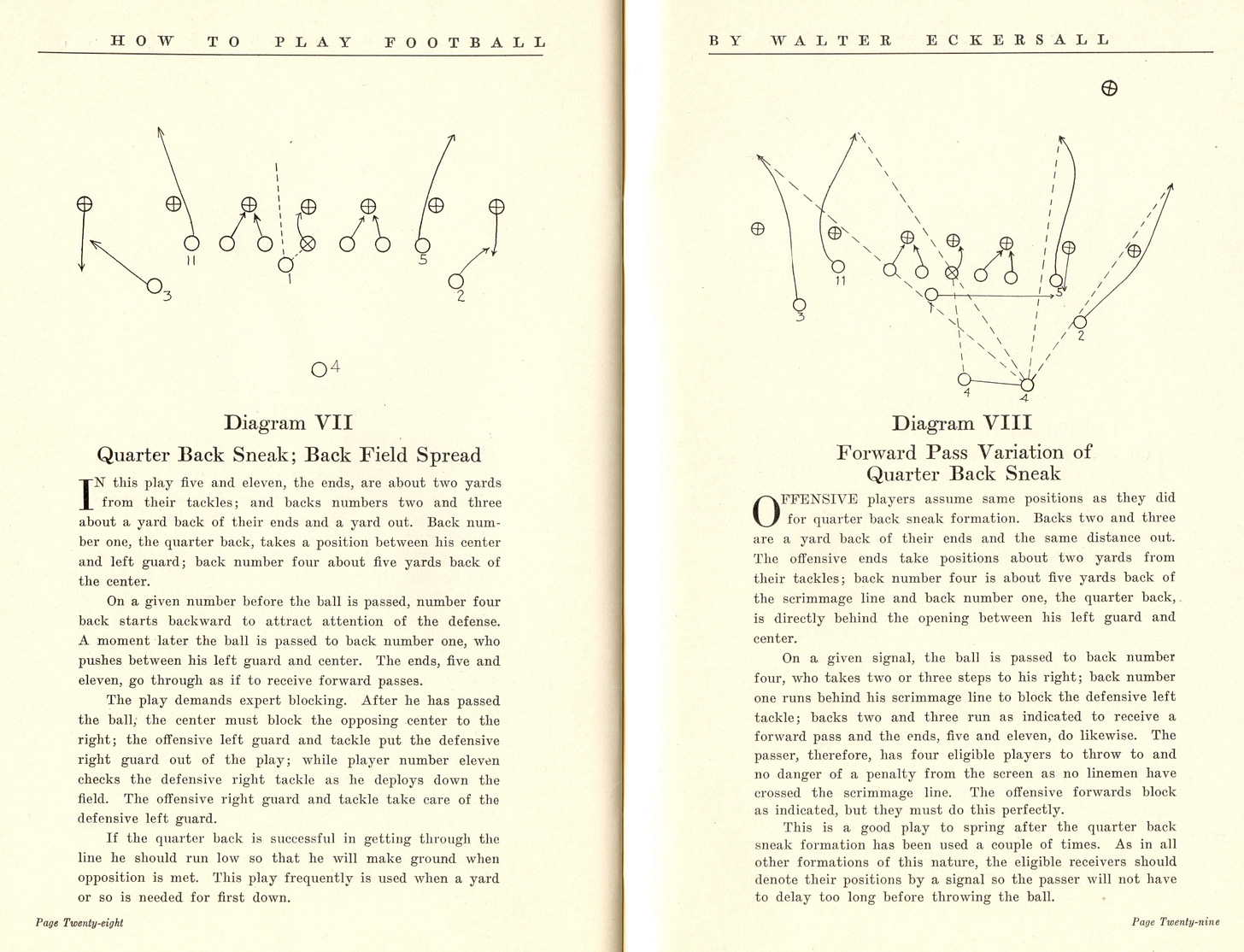

Another standard play and passing formation in the late 1920s was the quarterback sneak and pass off the sneak. An earlier article covered the development of the quarterback sneak, and Eckersall's play diagram shows it run from the Double Wing. The offense surprised the defense by snapping the ball to the offset quarterback, who did not usually carry the ball. A pass from the same formation sent four receivers downfield while the quarterback blocked the defensive tackle on the opposite side. We don't see that happen much nowadays.

So, when Eckersall wrote his booklet in 1928, the quarterback role remained similar to its place in his playing days. The forward pass was more important than in 1906, but the quarterback often was not the team's passer. Fullbacks and halfbacks handled that role. The shift to the passing quarterback only occurred once the Modern T and dropback quarterbacks arrived with Stanford and the Chicago Bears in 1940, with Clark Shaughnessy being the shared link. Only then did quarterbacks become passing specialists, so Eckersall would have been a star quarterback through the 1930s and into the 1940s. How he might have fared after former halfbacks like Sammy Baugh, Sid Luckman, and Otto Graham redefined the quarterback position would have depended on his ability to fling the ball, and that is a question we cannot answer.

Oh, and Happy Halloween!

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.

What an interesting figure in gridiron history Eckersall was. I love the statement "quarterback's role in 1906 remained tied to the past rather than the pass."

I certainly hadn't heard of him before this article.