Canada’s Heisman Trophy: The Hec Crighton Award

Few American football fans can identify the award bestowed on Canada's top collegiate football player or name the most recent winner, but that situation ends now. You now know that Tre Ford, the University of Waterloo Warriors' dual-threat quarterback who finished in the top ten nationally in both passing and rushing, was Canada's top player in 2021, earning the Hec Crighton Award. Of course, that knowledge leads one to ask: Who was Hec Crighton, and why did Canada name its top college football award after him?

Since this article inherently compares Hec Crighton to John Heisman, let's talk about Heisman for a minute. Heisman was among the diaspora of Ivy League football players who spread across the United States in the 1890s to coach football in the football wilderness to the south and west of Pennsylvania. He won seventy percent of his games as the coach at eight schools over thirty-seven seasons. Heisman was an innovator, an early advocate of legalizing the forward pass, but others of his day cast a longer shadow on football than Heisman. America's top college football award is named after him because he became the director of Manhattan's Downtown Athletic Club after retiring from coaching and had the misfortune of dying soon after the club awarded its first trophy in 1935. They renamed the trophy the following year, so the Heisman is named after Heisman due to circumstance more so than his impact on the game.

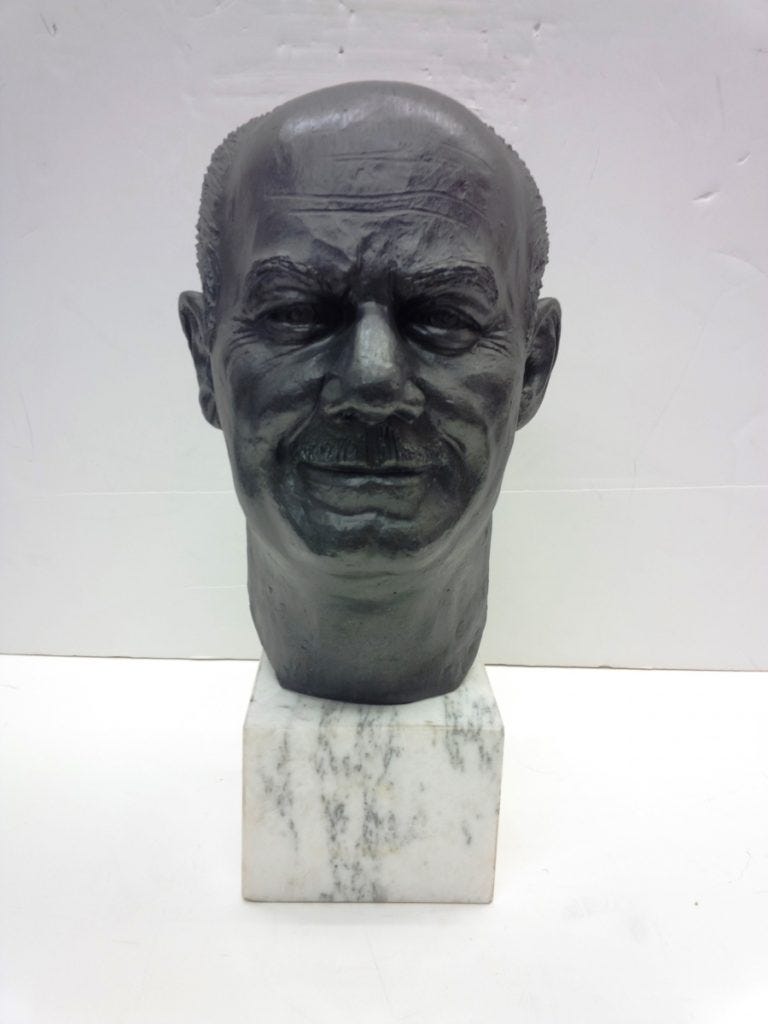

While Heisman's contributions to American football came as a coach, Hector Naismith Crighton's primary contribution to Canadian football occurred as a referee and rules committee member, impacting Canadian football analogously to Walter Camp's role in American football. Whereas Camp played a vital role as American football evolved from rugby during the game's first fifty years, the Canadian game remained more rugby-like well into the Twentieth Century. In fits and spurts that occurred at different times in Eastern and Western Canada, Canadian rugby incorporated elements of American football while retaining aspects of rugby that provide its distinctiveness. Importantly, Crighton sat in the middle of that process and helped the game balance its competing interests.

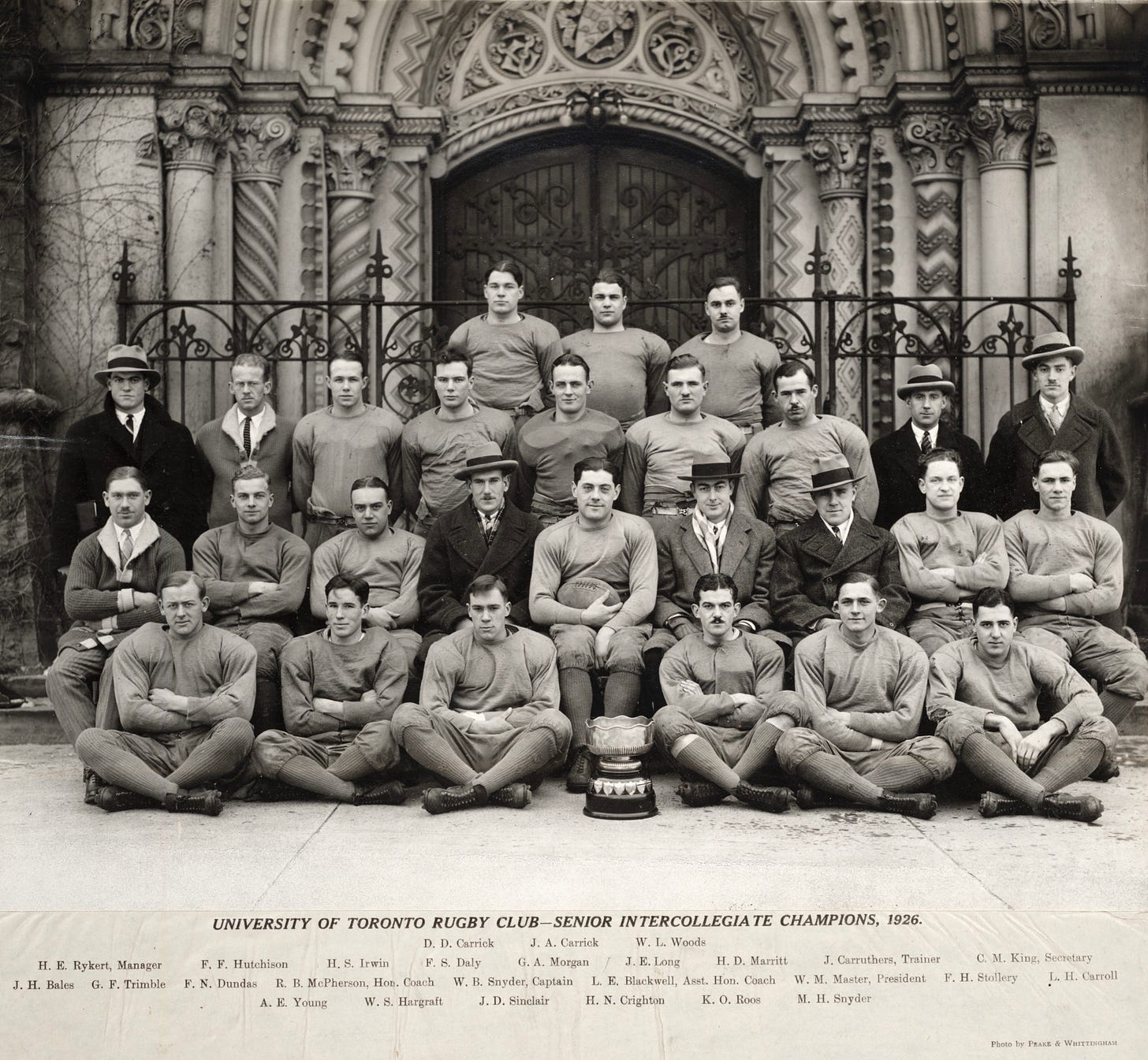

As a player, Crighton was the undersized quarterback of the University of Toronto rugby team in the mid-1920s. During his playing days, which ended more than a decade before the forward pass entered the Canadian game, the Varsity Blues were among the country's top teams, so he was a top-level player.

Crighton then taught and coached at the high school level for 25 years, primarily in Toronto. During that time, he left Toronto for Windsor for three years and was also absent while overseeing the physical conditioning of Royal Canadian Air Force personnel in Europe during WWII. However, he was a Torontonian aligned with the game's Eastern tradition and rules, not the more Americanized version popular in the Western provinces.

Crighton started officiating high school games during his college days and quickly rose through the ranks, handling high school, then junior and senior-level games. Widely viewed as the game's top referee, he handled a record sixteen Grey Cups during the time college and amateur teams competed for the Cup, and it later became the award for the country's top professional team. In addition, he played a significant part in supervising officials for various leagues and developing the game's rules throughout the period, literally rewriting the Canadian Rugby Union rulebook in 1952.

Although Crighton had a favorable view of Canada's game taking on American elements, he considered the post-WWII invasion of American players and coaches problematic. As he wrote in It's Time To Bring Back Canadian Football, a 1954 article in Maclean's magazine, Crighton was troubled by eight of the nine professional teams in Canada being coached by Americans, while American players often made double their Canadian counterparts. In his view, American coaches saw Canadian football through red, white, and blue glasses, failing to take advantage of the unique elements of the Canadian game. For example, despite Canadian rules allowing multiple men in motion, American coaches relied on the standard T formations used in the U.S. that had all but one back remain stationary pre-snap. Likewise, American coaches emphasized the forward pass at the expense of multi-lateral end runs on Canada’s wider field, onside kicks from scrimmage (players on the kicking team could recover and advance punts), and return kicks (immediately punting the ball back to the punting team).

His Maclean's article caused a stir in Canadian football circles, resulting in Crighton being blackballed from the professional game for casting doubt on the game's direction. Still, he continued supervising college officials, rewrote the Canadian Intercollegiate Athletic Union rulebook in the early 1960s, and remained a top figure in Canada's college game for the next decade.

Crighton fell ill in 1966 and passed away in April 1967. His obituaries recognized him as having been the game's top referee for several decades, a key influence on the game's modernization, and his appreciation of the unique elements of the Canadian game. Several months later, the Canadian College Bowl announced the creation of the Hec Crighton Trophy to be awarded annually to the nation's top collegiate player.

Like the Heisman, running backs and quarterbacks are the primary recipients of the Hec Crighton Trophy, though five receivers have won the award. Unfortunately, despite being the top college players in Canada, the award winners' success in professional football has been relatively modest. Part of the issue is that only twenty-one colleges play football in Canada – a twenty-second is a member of the NCAA- and they do not generate the number of players produced by America's nine hundred football-playing colleges and universities.

In addition, like the Heisman, the Hec Crighton Trophy is primarily awarded to "skill" position players, particularly quarterbacks, and the CFL does not favor Canadian quarterbacks. While the CFL reserves half its roster spots for Canadian players, teams typically fill high-impact roster spots from the deeper pool of American players. Hence, Canadian quarterbacks and running backs are relatively disadvantaged compared to Canadians who play other positions. (The quarterback position is also exempted from the fifty percent rule.)

In the end, like the Heisman Trophy in the U.S., the Hec Crighton Trophy goes to Canada's best collegiate player. Still, it seems fitting for the award to be named after an individual who played a crucial role in overseeing the game's evolution, accepting imported ideas as appropriate but arguing for retaining those elements that make the game distinctly Canadian.

Click here for options on how to support this site beyond a free subscription.