CFL-XFL Interleague Play? A History of Canadian-American Football Games

International travelers know electrical devices designed for one region require adapters to function in other areas. Thankfully, the U.S. and Canada share electrical standards, so our devices are interchangeable, but our football systems are not. They are sufficiently similar to allow cross-border play but different enough that Canadian and American teams must adapt their rules to take the field against one another. So, let's review the adaptations used in 150 years of cross-border football.

As every self-proclaimed student of football history knows, the first football-like games between Canadian and American teams came in 1874 when McGill University introduced rugby to Harvard. Those matches ultimately led the U.S. down the rugby path rather than the soccer path, so we are forever grateful to our Canadian friends for the nudge, but our games' evolutionary paths diverged a few years later. Americans reshaped their game with the scrimmage, the system of downs, and by allowing interference or what we now call blocking. Canada wandered from English Rugby as well but remained more rugby-like. Canadian Rugby borrowed the scrimmage and downs from American football. Still, it did not allow interference until parts of Canada adopted the Burnside Rules in 1903, which increased their alignment with the American rules of the time. Even then, Canada did not allow blocking more than three yards (later ten yards) beyond the line of scrimmage. The Northern folks also did not allow the forward pass until 1931, relying instead on rugby's punts and sweeping laterals to advance the ball.

Canada also used a larger field, allowed men in forward motion at the snap, and had only three downs to make a first down, along with other silliness. (As covered in an earlier article, the truth is that most differences in the countries' previously-shared rules resulted from changes made by the latitudinally-challenged half of the equation. Americans are the problem, not the Canadians.) The Canadian game also stood by its British roots longer than America in that Canadian colleges never developed athletic scholarships at a level approaching the U.S. Moreover, the top level of football in Canada remained an amateur game (with some ringers) until the late 1950s.

After the Harvard-McGill matches, the Universities of Michigan and Toronto played cross-border games in 1880 and 1881 when both still played a game almost identical to English Rugby. After the U.S. and Canadian games diverged, the first identified international game came when North Dakota hosted the Winnipeg Shamrocks in 1903. Being less than gracious hosts, the North Dakotans required they play under American rules and, the Shamrocks, ill-prepared for those unlucky conditions, were thrashed 57-0.

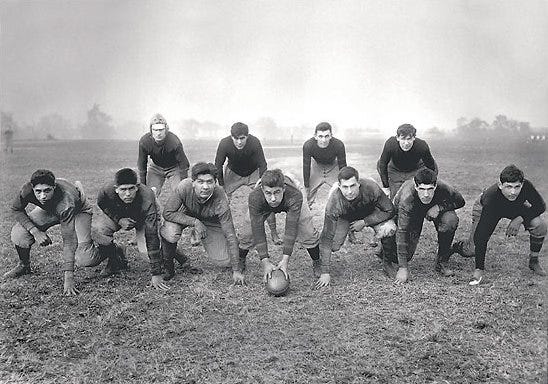

The next known international game came in 1912 when the University of Toronto challenged Carlisle, a Pop Warner-led team willing to play anybody anywhere. To squeeze Toronto into an already packed schedule, Carlisle topped Georgetown on a Saturday, boarded an overnight train, played in Toronto on Monday, before spending the evening heading back to Carlisle to prepare for Saturday's game with Lehigh.

The first half of the Toronto-Carlisle game used American rules and officials; the Canadians ruled the second half. During the first period, the Varsity Blue's lack of familiarity with downfield blocking led to Carlisle running over and around Toronto, as Jim Thorpe and his pals raced to a 44-0 halftime lead. Using Canadian rules in the second half, Carlisle earned a five-point touchdown, and Toronto made a rouge by tackling Thorpe, the only rouge of his career, after he caught a punt behind his goal line, producing a final score of 49-1.

Syracuse and McGill played a home-and-home series in 1921 and 1922, with both games using American rules. The same happened the following year when the early-NFL Akron Pros brought their American rules when visiting the Toronto Argonauts. The 1923 cross-border game between the Toronto Argos and the U.S. Third Army Corps was among the first football games played in Yankee Stadium. The Third Army Corps roster had all-stars from bases along the East Coast, many with college experience. They also had decent coaching. An old West Pointer named Eisenhower was in Panama in 1923, but was the team's head coach in 1921 and had a return engagement in 1927. It seems crazy now, but top U.S. service teams of the era competed with most anyone and were fan favorites with crowds that often doubled those drawn by top professional teams. Playing once again under American rules, the Third Army Corps drilled the Argos, 55-7.

Why would Canadian teams accept playing full games under American rules? There were several reasons, but surely one was boredom. The Argonauts were members of the Interprovincial Rugby Football Union, which had four teams. (Toronto and buddies Ottawa, Hamilton, and Montreal.) Likewise, the Intercollegiate Rugby Football Union had Toronto and two others, Queen's and McGill, and you can only play the kids down the block so many times before wanderlust sets in. Playing American teams provided a test against top competition; doing so by U.S. rules was the price paid to schedule those games.

Moreover, the 1920s saw an increased call in Canada to adopt elements of American football. The Canadian Rugby Union adopted the forward pass in 1931; their rugby ball was streamlined as well. Thus, the cross-border games of the 1920s provided an opportunity to gain new experiences and test the waters. By all accounts, the new experiences worked both ways in that the buck lateral and similar lateral-oriented series reemerged in American football due, in part, to exposure to Canadian Rugby.

From the beginning, most cross-border games featured college teams from states that border Canada. Michigan State crossed the Detroit River to play Assumption College of Windsor, Ontario, in the 1910s and 1920s. North Dakota resumed its series with Winnipeg in the mid-1930s and early 1940s when the Blue Bombers were still amateur. Their 1940 game used a blend of Canadian and American rules.

Cross-border games took on a different look with the start of exhibition games between professional teams. The first pro games occurred in 1941 when the Columbus Bulls held the first several weeks of training camp as guests of the Winnipeg Blue Bombers. Like most top senior teams of the time, the Blue Bombers were amateur in name with a handful of paid players on the roster. The Columbus Bulls were two-time champions of the American Football League, the third of four leagues to use that name. At the same time, the Blue Bombers were the returning champs of the three-team Western Interprovincial Football Union. Playing under Canadian rules but allowing downfield blocking, the Blue Bombers won the first game 19-12. (The Bulls suited up just fourteen players). After more Bulls players reported to camp, the Bulls won the next two games, 6-0 and 31-1.

Later that season, the Blue Bombers played a home-and-home with the Kenosha Cardinals, the last independent professional football team, who went 0-7-1 against NFL teams that year. The Cardinals won both contests despite playing under primarily Canadian rules.

The 1945 Detroit Lions beat their neighbors across the river, the Windsor Rockets, 40-0, in an exhibition game, though the game rules are unclear. There is more clarity about the rules used when the Ottawa Rough Riders hosted the New York Giants in 1950. Playing the first half under Canadian rules on a Canadian-sized field, the Giants led 13-6 at the half, but playing on the narrower field with downfield blocking in the second half, the Giants scored twice more and returned to Gotham with a 27-6 victory. Essentially the same story was told in 1951 when the Giants held a narrow lead at halftime before winning 41-18.

The 1950s may have been the most interesting decade in the relationship between Canadian and American professional leagues. The top Canadian teams increasingly professionalized with the founding of the Canadian Football League in 1958, the final break from the amateur Canadian Rugby Union. Canadian teams sometimes got into bidding wars with the NFL for players, most famously when Billy Vessels, the 1952 Heisman Trophy winner and #2 pick in the NFL draft, signed with the Edmonton Eskimos rather than the Baltimore Colts. Also, with only one college or NFL game broadcast on Saturdays and Sundays in most American communities, competing networks showed Canadian football games. It was not uncommon in the 1950s for Americans to have greater access to televised games of Canadian football than American.

Despite the competition, cross-border play resumed in 1959 when the Chicago Cardinals visited the Toronto Argonauts, winning 55-26 before more than 27,000, then the largest crowd to see a football game in Eastern Canada. The game also brought a new approach to the rules. They followed NFL rules when the Cardinals were on offense and CFL rules when the Argos had the ball. That meant the Argos' offense could not downfield block while the Cardinals could, and the Argos only had three downs to gain ten yards, while the Cardinals had four, but hey, those Canadians are gracious hosts.

The Argos hosted again in 1960, welcoming the Pittsburgh Steelers who, playing under Canadian rules, won 43-16. The following year saw three games between Canadian and American professional teams. The Bears and Alouettes played a close first half under Canadian rules, but the American rules used in the second half allowed the Bears to walk to a 34-16 win. As in 1959, the 1961 Toronto Argonauts hosted the Cardinals, then roosting in St. Louis. It is unclear which rules applied, though we know each team scored at least one single or rouge, with the Cardinals winning 36-7.

The third game in 1961 was the first and last between a Canadian Football League and an American Football League team (at least the version of the AFL that later merged with the NFL). The 1961 version of the Buffalo Bills traveled to Hamilton to take on the Tiger-Cats. Still wearing the Honolulu Blue and silver colors they stole from the Detroit Lions, the Bills played cowardly, losing the Canadian-rules game 38-12.

Perhaps the Bills’ loss was for the best since it marked the last time a CFL team played an American-rules team. (The U.S.-based CFL teams of the 1990s do not count.) Whether it was the consistent drubbings the CFL teams suffered against NFL teams or the influence of NFL television contracts, the two leagues went their separate ways and have not played since. Similarly, other than the occasional D-III game or the one or two Canadian colleges that belong to the NCAA, games between Canadian and American colleges became rare after WWII. High schools in border states play a few games now and then, but that's about it for Canadian-American play.

The last item of note about these cross-border games was the playing field. Newspaper articles serving as background for this article consistently mention game rules but seldom mention the field or its markings. Absent other information, I assume they used each stadium's standard field configuration, whether Canadian or American. The fact that a regulation Canadian field does not fit in most American stadiums presents a challenge for future CFL-XFL cooperation.

Beyond field dimensions, all other rules are negotiable, especially for exhibition games. Still, the history of cross-border games tells us numerous solutions or compromises are available so future teams can play ball if the desire is there.

Click here for options on how to support this site beyond a free subscription.