Charlie Finley and his Visually and Grip Enhanced Footballs

During Charlie Finley's time as the owner of the Oakland Athletics, he enjoyed challenging the norm, mainly when it came to uniform and equipment aesthetics. He was the first to have his baseball team take the field wearing white spikes rather than black, and he promoted the use of an orange baseball, which did not gain acceptance because hitters could not pick up the ball's spin.

Finley also owned the NHL's Oakland Seals and the ABA's Memphis Tams. His only foray into owning a professional football team was a proposal for a new league that was to combine U.S.-based teams and the CFL. He planned on owning the league's Chicago franchise, but the league did not move forward.

Somehow the football burr remained under Finley's saddle and led to him devising two changes to footballs, both of which he marketed through Wilson and Rawlings. Finley filed his patent application for the Visually Enhanced Football in May 1989 and the Grip Enhanced Football (aka the Double Grip) in September 1989, and by then he was knee-deep in his promotional efforts.

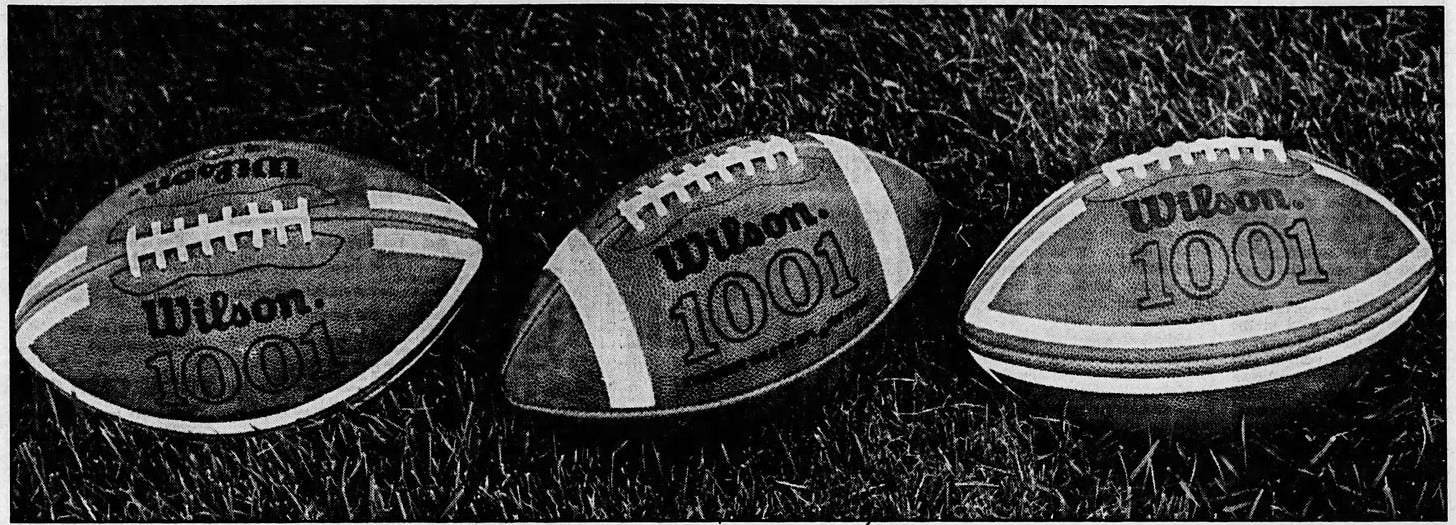

Visually Enhanced Football

Footballs earned their stripes in the 1930s because they helped players and the crowd see the ball during games played under lights that were often none too bright. Although there were variations in the location and number of stripes early on, the game settled on 1-inch wide transverse stripes applied between the laces and the tip at either end of the ball. Ol' Charlie had a better idea or, at least, a different one since he applied eight 1/2-inch longitudinal stripes, reasoning that his pattern helped everyone see the ball at night, particularly at the nation's high school stadiums he viewed as having inadequate lighting. Of course, he thought his striping pattern made sense for daylight games as well, so they produced a day version of the ball with white stripes while the night version had fluorescent yellow stripes.

The Visually Enhanced Ball stripes sat on either side of the ball's seams, reaching nearly to the tips and stopping about an inch short of the laces. Newspaper articles of the time claim the Visually Enhanced Ball saw its first use in two different Indiana and one Florida high school games, but that may be due to Finley's promoting each game as the premiere event. The ball saw use in high school games in eight or nine states during the 1989 season, receiving mixed feedback. Fans thought the ball was easier to track as it spiraled through the air on passes, and an official noted its longitudinal stripes made it easier to track the ball as it tumbled end-over-end on field goal attempts. However, some receivers thought the ball was more difficult to catch because it was harder to distinguish the ball’s outline compared to balls with transverse stripes.

Not to be deterred, Finley convinced the powers that be to use the ball in the 1989 Blue-Gray Game and the 1990 Hula Bowl. He also pitched his ball to a cooperating rules committee for the high schools and the NCAA. He gained approval from the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFSHSA) for use in 1990, assuming both teams playing in a game agreed to its use.

Despite the ball's approval, it did not gain acceptance and disappeared from the scene as quickly as it had arrived. The alternate striping pattern did not provide enough benefit for teams to justify buying them rather than the old reliable. And a related legal issue, described below, arose that did not help the situation.

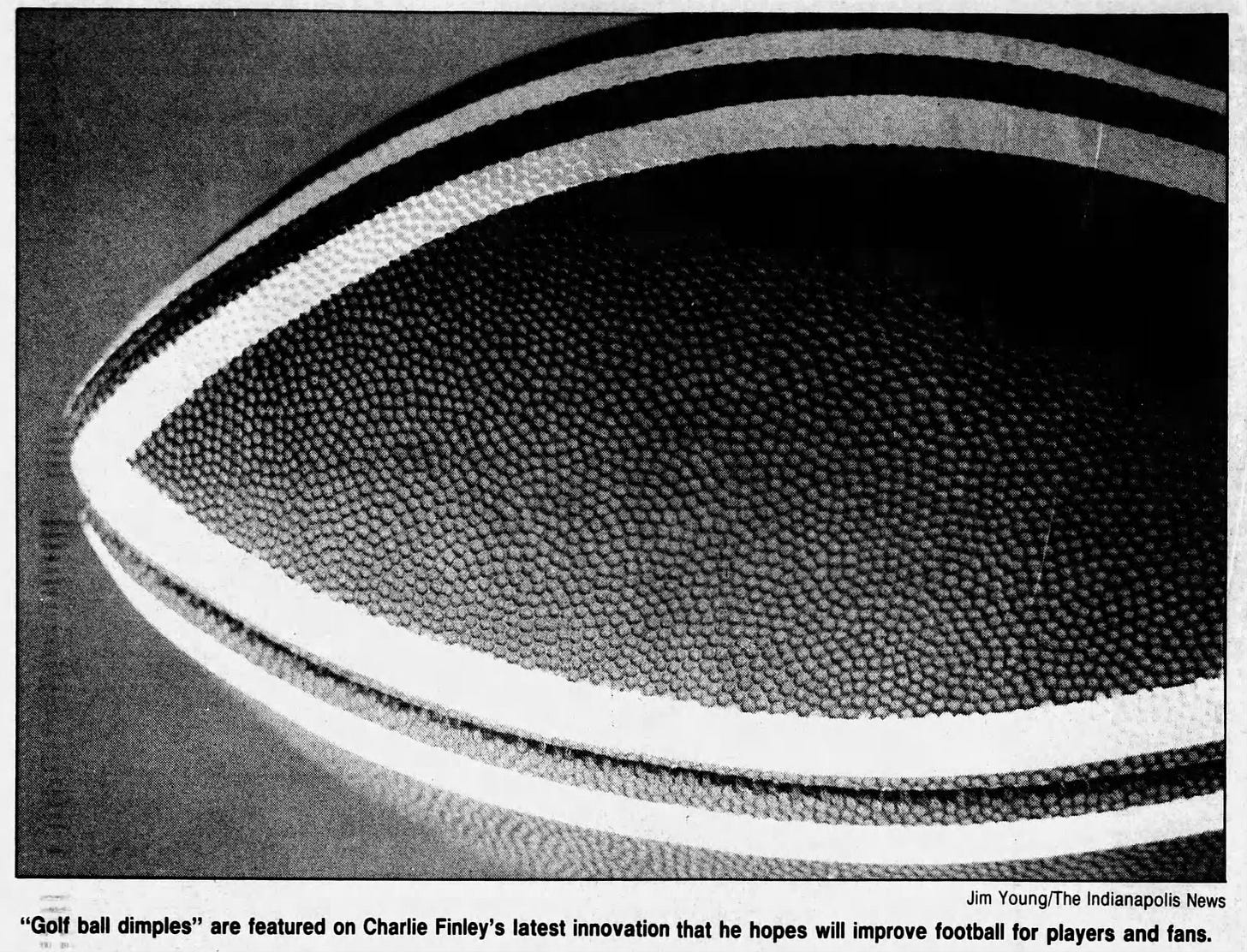

Grip Enhanced Football

Finley's other innovation was the Grip Enhanced Football, which aimed to improve the quarterback's grip and ability to put spin on the ball, while reducing fumbling, and enhancing receivers’ ability to catch the ball. It also flew farther, as demonstrated by testing conducted with JUGS machines.

The secret to the Grip Enhanced Football was its leather, produced by Chicago's Horween Leather Company, the provider of the leather used in manufacturing NFL footballs then and now. Rather than the leather's grain having raised pebbles, it had small dimples, much like a golf ball.

The ball received NCAA approval in October 1990, with Michigan quickly adopting it. It turns out that Finley had met Bo Schembechler during Bo's several-year role as president of the Detroit Tigers following his time at Michigan. Bo connected Finley with the Wolverine's equipment manager, who became intrigued by the ball and promoted its use internally.

Michigan used the ball during the rest of the 1990 regular season and in its Gator Bowl appearance. Eight other teams used the ball during that season's bowl games, though everyone appears to have used the Grip Enhanced Ball with standard striping - transverse stripes on the two panels next to the laces and no stripes on the bottom panels.

It is unclear how many teams used the Grip Enhanced Ball in 1991, but Michigan did and had a great season, losing only to #1 Florida State in the third game of the season and to #2 Washington in the Rose Bowl. Elevating the ball's status was Elvis Grbac, who lead the NCAA in passing efficiency, and Desmond Howard, who won the Heisman Trophy after scoring 19 touchdowns on pass receptions, including one or two of the circus variety.

While Michigan's 1991 season might have convinced others to appreciate the value of dimples, only Wyoming, Kent State, and Rice joined the Wolverines in using the ball in 1992 before the Grip Enhanced Ball encountered two problems. One came when Rawlings, who produced the ball, asked the courts to invalidate Finley's patent, claiming that Finley was not the inventor of dimpled leather. How that battle turned out is unclear, but the legal wrangling likely made Rawlings less willing to promote or even produce the ball.

The second problem came in November 1992 when Michigan hosted Illinois on a cold and snowy Ann Arbor day. Apparently, the ball did not like the cold weather, becoming stiffer and slicker than the traditional pebbled ball. Michigan had 17 fumbles, interceptions, dropped balls, or botched PAT holds that day, while Illinois had only one using pebbled balls. Michigan used the Grip Enhanced Ball the following week versus Ohio State without incident but returned to the pebbled ball when they avenged their loss to Washington in the 1992 Rose Bowl by beating them in the 1993 Grandaddy.

Like the Visually Enhanced Ball, the Grip Enhanced Ball or "Double Grip" ball quickly faded from public view and presumably from use as the product went unmentioned in the press after that. As with all new ideas, there is a fine line between an innovation and an oddity. So far, the football world has relegated both of Charlie Finley's football ideas to the oddity pile.

BTW, the recorded version of the first Football Archaeology Dig is available for viewing.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.

I agree that the transition from one stripe pattern to the other may be the key. The were some references to the poor performance in the cold being due to ice or slush resting in the dimples. At least, that is what their competitors argued.

I wonder if players started with the visually enhanced ball what they would think switching over. I suspect they’d find the transition even worse.

The poor weather performance is strange