Confusion Reigned Before Penalty Signals

Football is information-rich today, but it was not always so. Before 1910, only a few teams had worn jerseys with numbers. Distinguishing one player from another and keeping track of the substitutes entering the game was problematic, even for coaches. Likewise, loudspeaker systems did not exist, and the scoreboards of the day were primitive -none had game clocks. The information challenge only grew worse as stadiums got bigger, further separating fans from on-the-field sights, sounds, and actions.

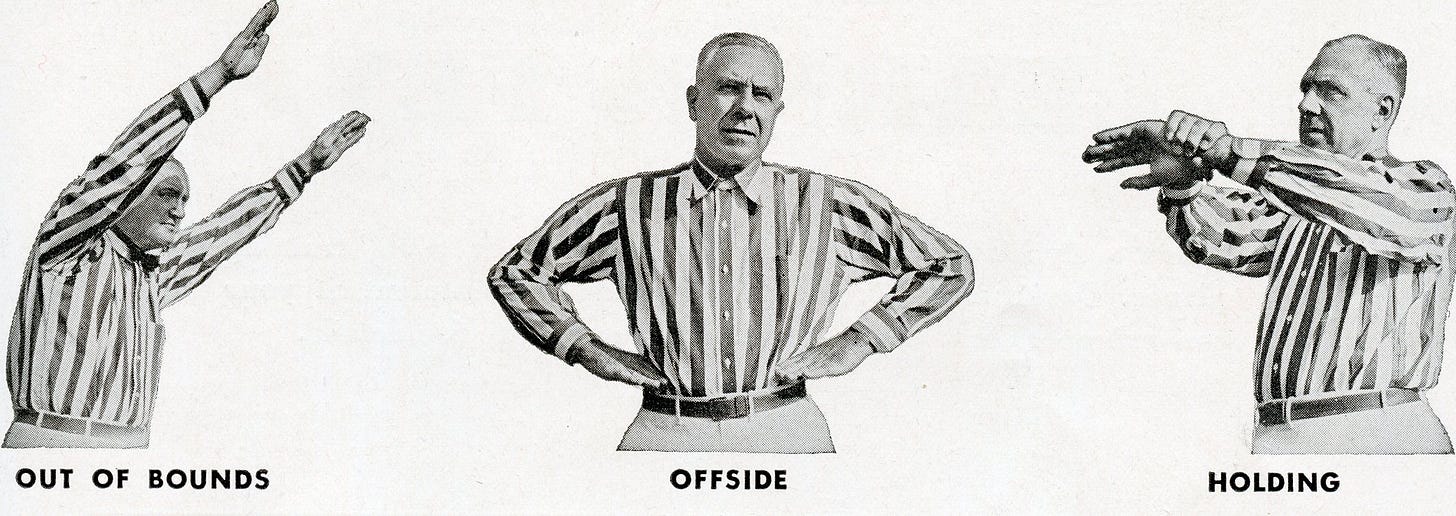

The game's officials did little to help the situation. The first penalty flag was not thrown until the 1940s, meaning fans could not tell when or where infractions occurred, which player committed the foul, or which official called the penalty. Those in the stands watched the referee step off penalty yards without any idea of why he did so. The referee's contortions we know as penalty signals would not become mainstream for a few more decades.

Of course, football aficionados recognized a problem and developed solutions, but no one could get it right. The first solution came from the naval and firefighting worlds, which used various voice enhancers to coordinate men in noisy environments. The megaphone, a term coined by Thomas Edison, became popular in the 1890s, with the 1894 Penn-Lehigh contest being the first to use a megaphone to inform spectators of gridiron goings-on. It is unclear who voiced the announcements or what was said, but megaphones had shortcomings when used to provide information to crowds in noisy stadiums. Each message had to be repeated left, right, and center and they seldom produced the volume needed to be heard above the din.

The noisy environment got worse when fans saw the megaphone's potential for generating sound. Harvard fans amplified their messages to Yale later that season. Penn cheerleaders used megaphones in 1897, two years before their use by Minnesota, who is often credited for pioneering the megaphone's use by sideline shouters. While fans and cheerleaders successfully used megaphones to generate incoherent noise, megaphones were ineffective in providing clear information about the nature of called penalties.

Beyond the challenge of sending a consistent message throughout the stadium, an equal challenge was ensuring the accuracy of the information. How could someone in the press box know which penalty was called when the officiating crew communicated only with the team captains? The solution came by positioning someone on the sidelines to monitor the conversations, who then signaled that information to others.

Harvard introduced such a system when they opened their new stadium in 1903. The Crimson had a man wearing a red vest positioned on the sidelines to listen to the referee's conversation with the captains. He then relayed the information to the scoreboard operators using hand and body signals, and they posted information about what had occurred.

Only a limited number of stadiums had the scoreboards and processes to display information on penalties, but those that did used a variation of Harvard's approach. At least one stadium had Boy Scouts follow plays and signal the scoreboard operators using semaphores. Folks in Hawaii printed penalty numbers in the newspaper for fans to cut out and bring to the game. Like Harvard, the operators displayed the penalty number on the scoreboard after receiving the signal from a man in the field. In 1928, they improved the process by connecting the sideline and scoreboard by telephone.

The final alternative arose in Pittsburgh during Elmer Layden's reign as Duquesne's coach. One of Notre Dame's famous Four Horsemen, Layden advocated for cheerleaders to signal penalties to the crowd. Duquesne used the cheerleader system in 1928, proving both visionary and archaic. It was visionary to have someone on the field signal the penalty, but it left the cheerleaders as middlemen between the referee and the crowd.

Today's solution came from Frank Birch, a referee who began signaling penalties himself using hand and body motions. Birch was a bit of a showman, famous for flying into piles to locate the ball, and he had the insight to give decoder sheets to the press starting in 1910. Birch's system had much going for it, but he implemented it at a time when football effectively had a running clock. Football's pace of play still resembled rugby in that offenses completed a play, quickly lined up for the next one, called the signals at the line, and snapped the ball. The clock stopped only for kicks and a few other situations at the referee's discretion. The clock did not even stop when the ref marched off penalty yards, so Birch had to spot the ball, move to his position behind the offensive backfield, and signal the penalty in the few seconds before the next play began. The signaling of penalties was not the time-consuming spectacle of today.

Birch's system was slow to gain acceptance. Referees already had a long list of duties, and rushing to signal penalties between plays was not a priority for most. However, conditions changed in the 1920s as teams began huddling and the game started its shift toward its current pace. It was not until 1929 that the officials' governing bodies recommended using signals, and 1934 before referee signals appeared in the NCAA rule book.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.