FDR and Herbert Hoover Went Over There with the 91st Division

After training at Camp Lewis for ten months, the 91st Division left Camp Lewis in late June 1918 for shipment overseas. Most units travelled by rail across the northern U.S. to the ports in New York and New Jersey, while the 363rd traveled through Canada on a public relations tour before shipping from Philadelphia.

The division's units were allocated across several ships for their journey to Europe. Parts of the 361st boarded the S.S. Karao in Brooklyn, with others sailing on the S.S. Scotian from Hoboken. The 362nd boarded the R.M.S. Empress of Russia in Brooklyn. The 363rd sailed on the S.S. City of Cairo from Philadelphia and the 364th boarded the S.S. Olympia. Unit histories written after the war indicate that two notables joined the 364th aboard the R.M.S. Olympic: then Under Secretary of the Navy, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and the head of the U.S. Food Administration, Herbert Hoover. The Olympic’s passenger list shows Hoover was aboard and he gave a speech to the men during their ocean passage, but FDR actually crossed the Atlantic on the U.S.S. Dyer, a Navy destroyer, though some of his staff traveled on the R.M.S. Olympic with the 364th. Nonetheless, both men were in the convoy as it headed east with the 91st Division, so let's take a look at the 91st Division's convoy and the roles FDR and Hoover played during WWI.

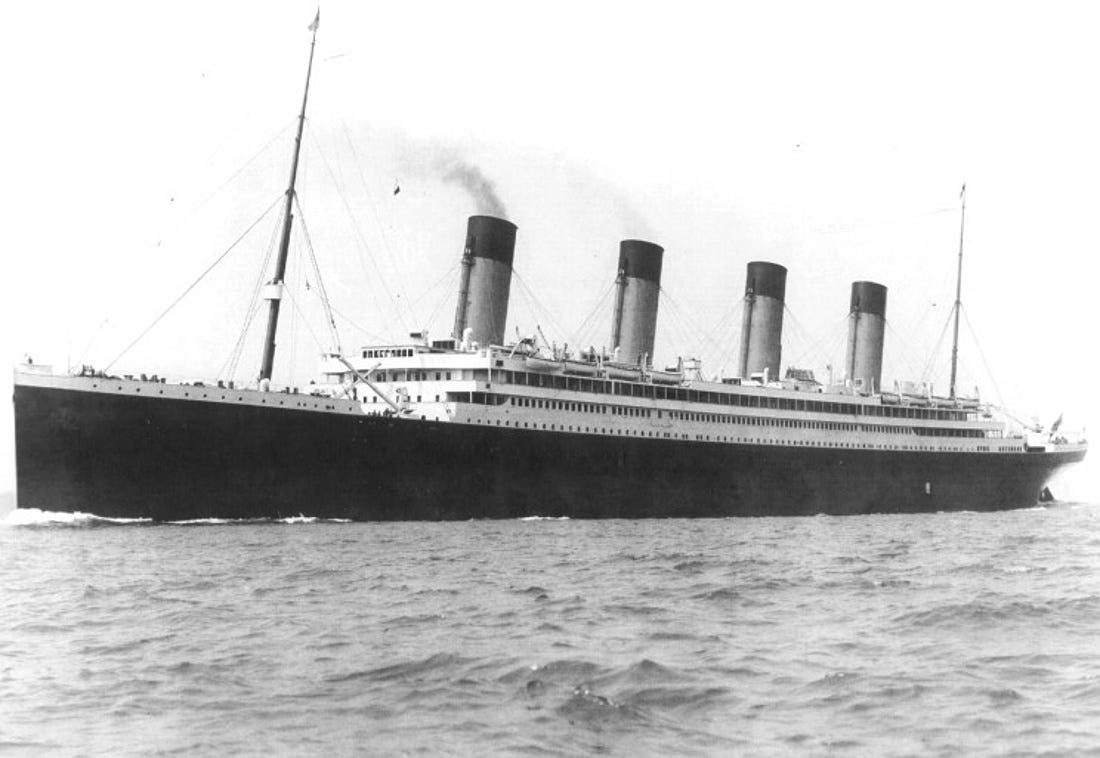

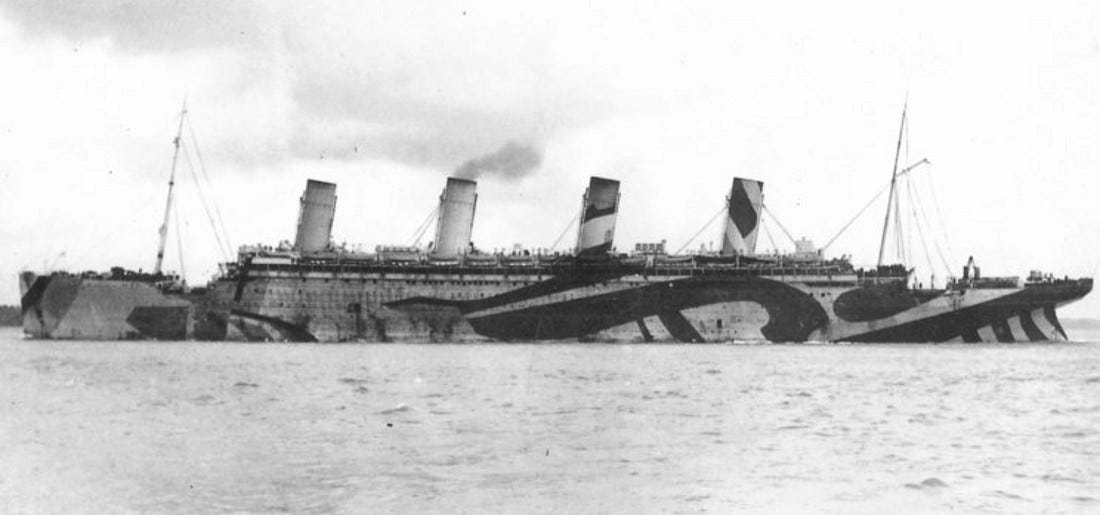

The S.S. Olympic was a White Star liner converted for use as a transport ship during the war. The Olympic had two sister ships: the Titanic, which sunk in 1912, and the Britannic, which sunk in 1916 after hitting a mine off of Greece.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt

As Undersecretary of the Navy, Roosevelt traveled to Europe on an inspection tour purportedly focused on ensuring the contracts, leases, and other business issues related to the Navy’s presence in Europe were in order. But he had other purposes as a high-ranking representative of the U.S. government. His itinerary included policy meetings in London with King George V, Winston Churchill, David Lloyd George, and Lord Balfour, and in Paris with Marshall Joffre, President Poincare, and Premier Clemenceau.

The U.S. had 250 warships in European waters by July 1918. The press covered of his trip provided an opportunity to update the nation on the Navy’s strategy and role in the war. As Roosevelt explained before leaving for Europe, the Navy had three key missions in the Atlantic. The first was to protect merchant and troop ships traveling to Europe. The second was to hunt German U-boats in the Atlantic and the third was to hunt German U-boats operating along the American coast. Roosevelt spoke of a triangle with its apex being the waters in which the Baltic Sea joins the North Sea. The base of the triangle extended from the West Indies to Newfoundland. The triangle’s apex was Germany’s only access to and from open waters, which the British had blockaded since early in the war, effectively bottling up Germany’s surface fleet for much of the war.

Herbert Hoover

Hoover was an interesting gent who laid claim to being Stanford University’s first student based on his having been the first student to sleep in the dormitory when Stanford opened its doors in 1891. He was Stanford's football team manager in 1892 when the first Big Game was played against the University of California. Following graduation, he became a wealthy mining engineer and investor and was living in London in 1914. Following the outbreak of war, he headed a committee that helped 120,000 Americans get back home from Europe. His leadership of this effort marked him for additional duties.

When Germany invaded France in 1914 they did so by attacking through neutral Belgium. The Belgians fought valiantly, causing critical delays in Germany’s invasion plans, but they were outgunned and Germany occupied almost all of Belgium for the next four years. There was vicious fighting on Belgian soil throughout the war – Ypres, Passchendaele, and Flanders are among the infamous battle locations – and agricultural production was unsustainable near the front. In addition, the Germans seized for their own use much of the agricultural production from the areas of Belgium that remained productive. This left too little food for the Belgians and they began to starve.

An international, but largely American-funded, relief effort called the Commission for Relief in Belgium, raised funds to provide food for the Belgians. Hoover led the effort and negotiated with the Germans and British to ensure the relief ships gained safe passage to Belgian ports. He worked tirelessly for several years for the Commission. After America entered the war, President Wilson asked Hoover to take responsibility for the U.S. Food Administration. Among other policies, the Administration created a massive publicity effort that encouraged Americans to limit their intake of certain foods to ensure those foods were available for the men fighting in Europe. Self-rationing through Meatless Mondays and Wheatless Wednesdays became known as ‘Hooverizing’ and the term became common slang for self-control and economizing. Few, if any, use the term today, but it was the cat’s pajamas in its day.

In his new role, Hoover was aboard the Olympic with the 364th Infantry when she slipped out of New York harbor headed to Europe on July 6, 1918.

The Convoy

Like other shipping to and from Europe, the ships that held the 91st traveled in a convoy –groups of supply and troop ships protected from German submarines by destroyers and other naval vessels. The convoy system was implemented around the time America entered the war and had two primary benefits. First, although WWI destroyers and other warships lacked effective sonar –meaning they could not spot the German U-boats underwater in advance of their attacks– once spotted, the destroyers did their level best to chase down the U-boats to ensure they never launched another torpedo. Second, the U-boats also lacked effective means of detecting Allied shipping so, while they patrolled areas likely to have Allied ships, finding them was a game of chance in the vastness of the ocean. Prior to using convoys, if fifty ships sailed independent paths to England, the Germans had fifty independent targets whose paths they might cross. By clumping ships into convoys, the Allies dropped the number of targets from fifty to one. Even though the one target had many more ships that could be torpedoed if found, the convoy system dramatically decreased German’s chances of crossing the one target’s path. Moreover, U-boats that attacked a convoy then had to deal with the destroyers and other ships defending the convoy.

The convoy that included the 91st, FDR, and Hoover zigzagged throughout the journey, taking twelve days to reach Liverpool. From Liverpool, the 91st traveled by rail to Southampton and then by channel boat to Le Havre, France, arriving on July 23.

Hoover returned to the U.S. in late August, announcing that relief efforts were having success, but stressing the need for continued self-rationing and the use of Victory Flour (wheat flour with twenty percent barley or other cereal substitutes). FDR returned to the States in September, while the 91st Division came home in April 1919 after fighting in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive and in Belgium during the last months of the war.

Click here for options on how to support this site beyond a free subscription.