Finding A Hero: Elijah W. Worsham and the 1904 Purdue Exponent

Although I published Fields of Friendly Strife: The Sailors and Doughboys of the WWI Rose Bowls in 2017, I continue to pursue additional information and items related to the football teams and players profiled in the book. As an example, a few weeks ago I acquired a copy of The Purdue Exponent, Thanksgiving Number published in 1904 that includes articles about the last several football games Purdue played that season. (A “number” in this context is a British term for a magazine “issue.” The term dropped from usage in the U.S. in the 1930s.)

The 1904 Purdue football team is notable for two reasons. First, before the age of automobile and airplane travel, football teams and fans traveled to away games by train. Schools commonly coordinated special trains that ran outside of normal schedules to transport passengers from their home campus to the game’s location. Such was the case on October 31, 1903, when two special trains left Lafayette, Indiana headed to Indianapolis carrying Purdue’s team and more than 1,500 fans to their rivalry game with Indiana. Upon entering Indianapolis, the first train, with members of the Purdue team in the first coach car behind the engine, rounded a bend and collided with a number of coal cars being moved in a switching yard. The team trainer, an assistant coach, and fifteen team members died of injuries suffered in the crash and another twenty-one team members were hospitalized. The tragedy cast a pall on the Purdue campus for the remainder of the academic year and brought particular attention to the football team as school opened in the fall of 1904 with only five team members returning from the previous year.

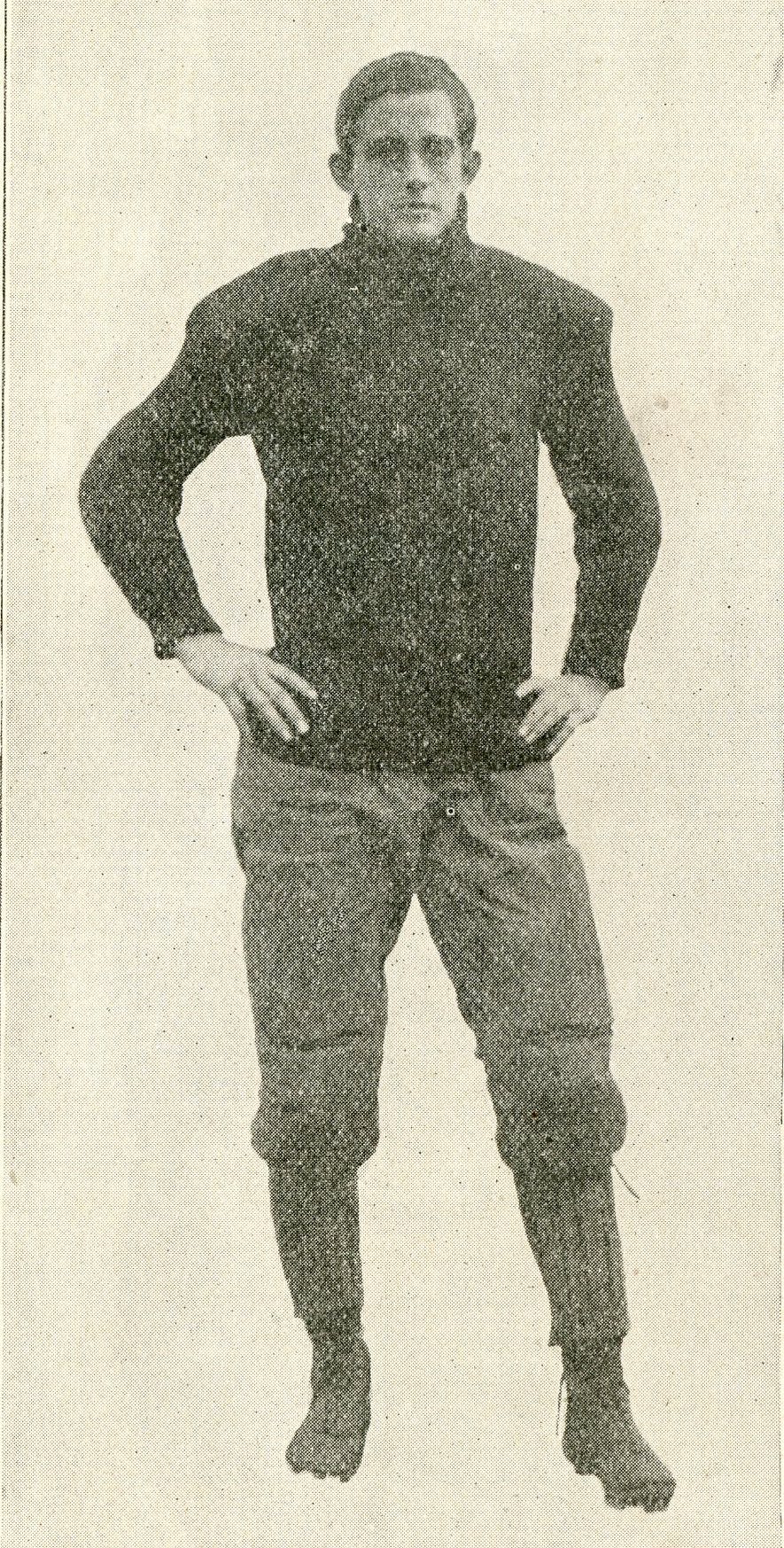

The second reason the 1904 Purdue team is notable is that a freshman from Evansville, Elijah “Lige” Worsham, joined the team and quickly made his mark as a halfback, scoring several touchdown during the season. The depleted team started the year slowly but fought through their struggles to finish with a 9-3 record including wins over in-state rivals Wabash, Indiana, and Notre Dame. A team that few expected to have success proved an inspiration for their fellow students and the broader community.

Perhaps the best example of the team’s never-say-die attitude came against Culver Military Academy, a prep school in northern Indiana. The 1904 season was played before the forward pass was legalized and before quarterbacks took the direct snap from center (click here for more on the evolution of the center snap), but the quarterback remained critical to the team because he called the plays. Coaches were barred from communicating with the team during play and there was very limited substitution, so the quarterback determined which play to run. The 1904 team also played before teams huddled so quarterbacks called the plays at the line of scrimmage through verbal and physical signals. As it happened, both of Purdue’s quarterbacks were injured in the first half against Culver and could not play in the second half. No one else on the team knew how to call signals or hand the ball to the running backs, so Purdue punted on first down each time they took possession of the ball in the second half and relied on the defense to sustain them. Purdue kept Culver scoreless in the second half, just as they had in the first half, and came away with a 10-0 victory.

Although he played on an inspirational team, Worsham did not, as far as I can tell, do anything particularly heroic while at Purdue. He left school after his freshman year and his football exploits might have ended then, but they had a brief revival more than a decade later tied to far more momentous events. Worsham spent the next few years managing a coal mine and coaching high school football near Evansville before moving to the Northwest where he later joined the Oregon National Guard as a member of a machine gun unit. Worsham was living in Seattle in April 1917 when America entered WWI, prompting him to enlist. His National Guard experience and one year of college qualified him to be among “The First Ten Thousand” or those selected for officer training who subsequently formed the cadre of the National Army of enlistees and draftees destined for France. As with others, Worsham completed officer training in August 1917, just in time to welcome the first round of draftees to Camp Lewis, a new training camp being built outside Tacoma.

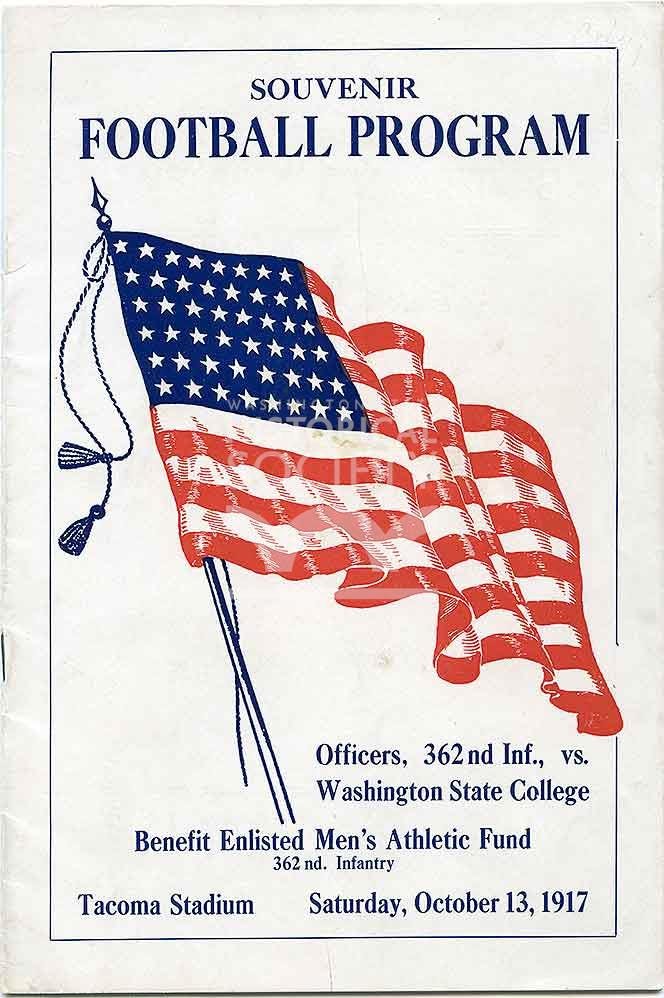

At Camp Lewis, Capt. Worsham took charge of the Machine Gun Company of the 362nd Infantry Regiment, 91st Division. With men pouring into camp with little to do in their off hours, Worsham and other officers saw the need to raise money to buy athletic equipment for their men’s entertainment. To do so, the 362nd Officers scheduled a season-opening football game against Washington State, which had a pretty fair team having won the 1916 Rose Bowl. Officers of one Army regiment playing a major college football team might not fly today, but times were different then and the 100+ officers in the 362nd Infantry included a fair number of former college football players. Though outplayed, the 362nd Officers held Washington State to a scoreless tie before 10,000 fans. Worsham gained credit for leading the team after their captain was injured on the game’s second play. The 362nd Officers played and won two other games that season, while four players from the 362nd Officers team joined the broader Camp Lewis team when it was formed. The Camp Lewis team lost only one regular-season game and was invited to play the Mare Island Marines in the 1918 Rose Bowl where they lost for the second time.

After the football season ended, the 362nd Infantry Regiment and the rest of the 91st Division returned to training for war full time. They shipped out in June and arrived in France on July 23, 1918. Leaving the port area a few days later, they entrained for the French interior. That evening the troop train stopped in the town of Bonnieres and was sitting on the main line when, shortly before midnight, a passenger train barreled into the station at full speed, crashing into the rear of the troop train. Seven of the troop train’s cars were demolished and others were thrown from the track. Twenty-nine men perished in the accident and seventy others were injured, most of whom were from Capt. Worsham’s Machine Gun Company. A contingent of officers and enlisted men stayed behind that night to see to the burials and injured, while the rest of the troops boarded another train to continue on to their training camp.

The 91st Division trained for an additional five weeks before being sent to the front lines, where they were held in reserve during the assault on the St. Mihiel Salient. As that battle ebbed, the 91st Division moved north for the coming Meuse-Argonne Offensive and were among the doughboys who went over the top on September 26, 1918. Three days later, Worsham was leading his company’s attack on the French village of Gesnes. He had proven fearless in the first several days of fighting and once again put himself at risk by moving ahead of his men to scout positions that might afford them some level of safety. Positioned on the crest of a knoll on which he was exposed to enemy fire, a German bullet found Worsham, killing him instantly. For his bravery that day, Worsham was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the second highest honor a member of the U.S. Army can receive for gallantry in action. The full story of the attack on Gesnes during which Worsham and two fellow officers who played on the 362nd Officers team were killed can be found here.

It is not uncommon to hear the word heroic used to describe events that occur on playing fields, but the story of Lige Worsham and others like him remind us of the true meaning of the word.

Click here for options on how to support this site beyond a free subscription.