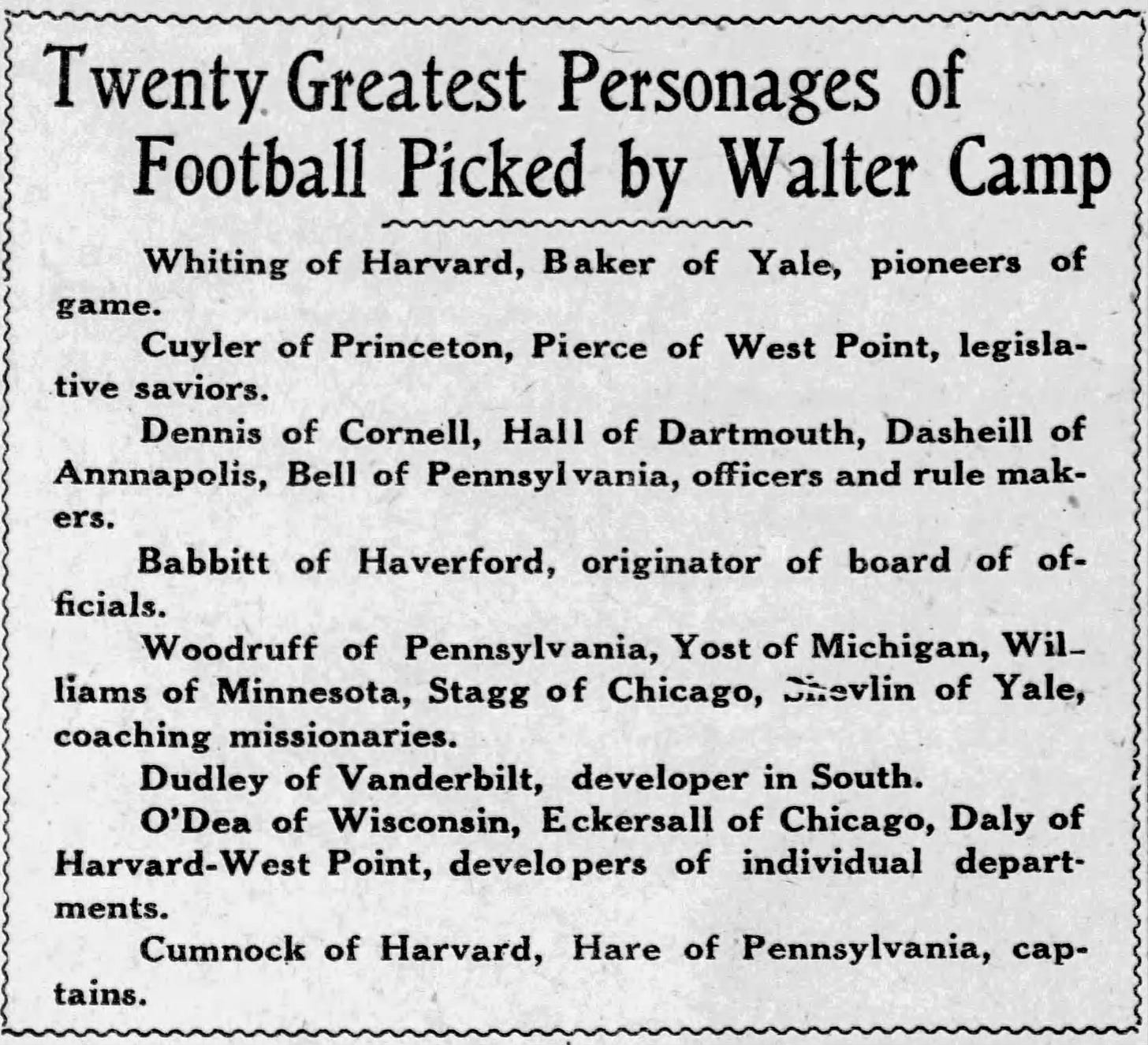

Football's 20 Greatest Influencers Per Walter Camp

We've all seen lists of the greatest players or top coaches in football history, and almost all suffer from recency bias. The greatest player lists have few athletes who played before 1960, and while lists of top coaches typically stretch back further, they are less likely to include someone who influenced a once-popular aspect of the game that has since died out.

The flip side of that effect is evident in a list published by Walter Camp in January 1912 after being asked to identify the 20 individuals with the greatest impact on football. I estimate that the average fan might recognize only three or four of Camp's top 20, while even knowledgeable students of football history will not recognize a few. Of course, Camp' stop 20 is a time capsule because he prepared his list before football fields had end zone, and the forward pass was in its infancy. Moreover, Camp was a player and coach, but his primary contributions came as an administrator. He helped organize the game and establish its rules on the field and off (e.g., eligibility standards). So, it is unsurprising that many of his top 20 played similar roles.

Camp introduced his list and the rationale for his selection with the following introduction:

Below are brief bios of each with relevant information through 1911.

Pioneers

The game's pioneers were the team captains of Harvard and Yale when American football began. Camp did not consider the 1969 Rutgers-Princeton game to be football's beginning. Instead, he saw the sport's origins coming in the mid-1870s.

William A. Whiting. Whiting captained Harvard's 1875-1876 team that played the Canadian All-Stars and the concessionary game with Yale.

Eugene V. Baker. Captain of Yale's 1876 and 1877 teams, the first of which earned Yale's first victory over Harvard 1-0.

Whiting and Baker represented their schools at the November 1876 IFA meeting at the Massasoit House that established American football' first consistent rules.

Legislative Saviors

C. C. Cuyler. A Princeton grad, Cuyler directed the University Athletic Club of New York in the mid-1890s and facilitated rule commonization after some schools broke from the IFA and established separate rules committees.

Palmer E. Pierce. West Point's athletic director in the 1890s, Pierce, chaired the December 1905 meetings of the newly-formed Intercollegiate Athletic Association (IAA) that set the direction for the 1906 rule changes. The IAA became the NCAA in 1910.

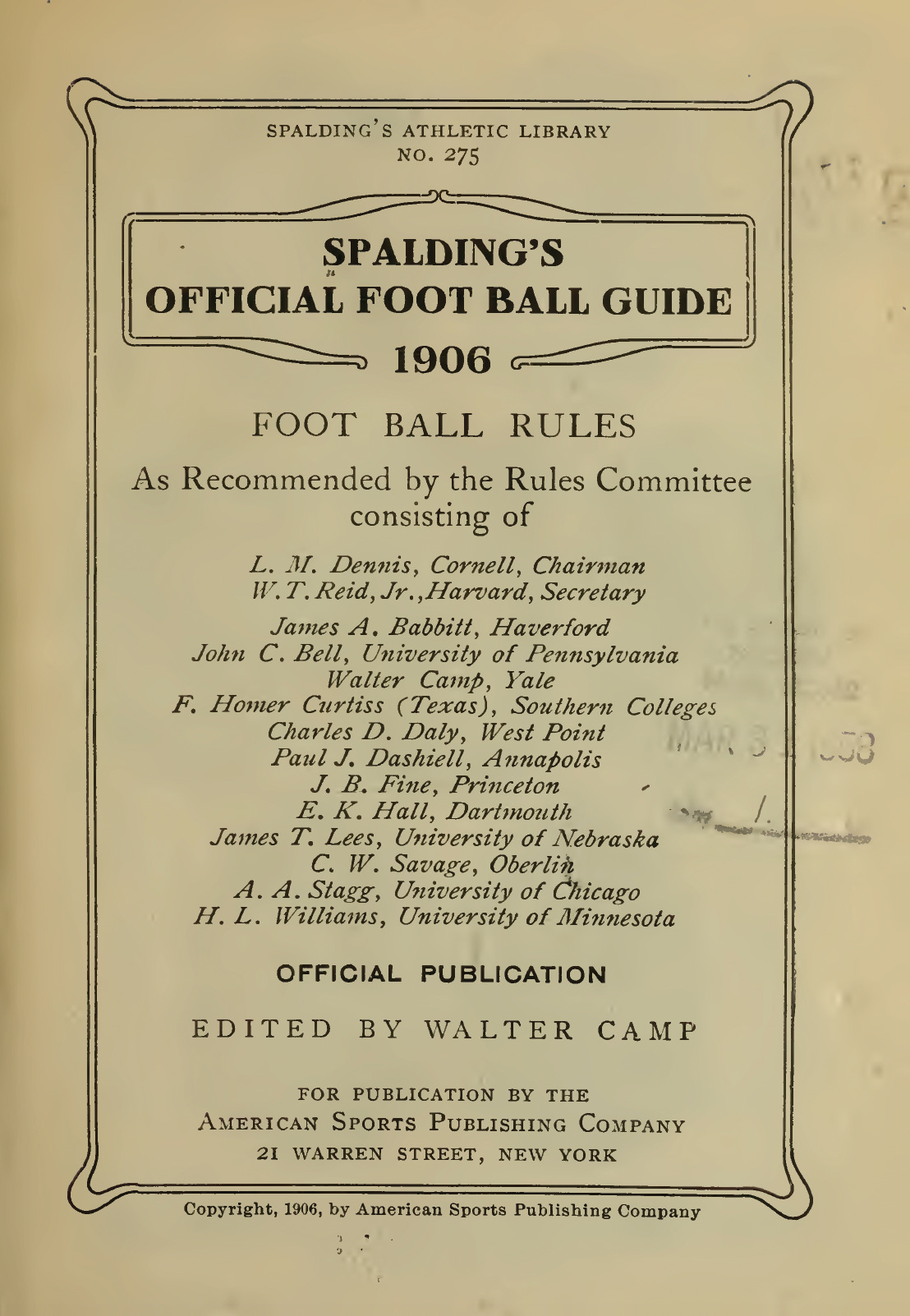

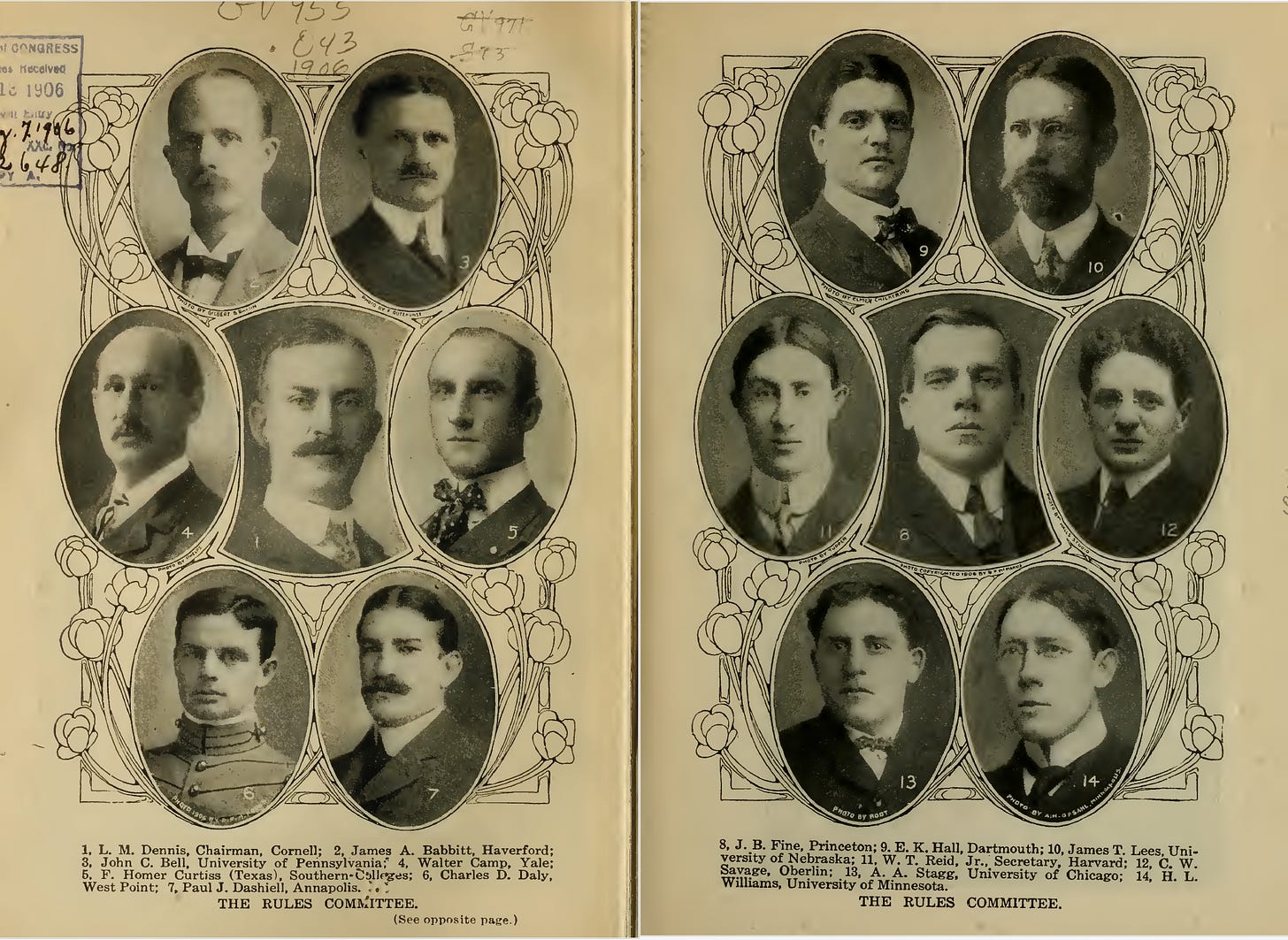

1906 Rule Makers

Five of Camp's Top 20 were 1906 Rules Committee members.

L. M. Dennis. A Cornell professor, Dennis chaired the IAA committee that consolidated and revised football's rules in 1906.

E. K. Hall. Hall played at Dartmouth from 1889 to 1892 and coached at Illinois for several years. After shifting to a business career, Hall was the rules committee secretary in 1906 and became its chair in 1911.

Paul J. Dashiell. Dashiell played at Johns Hopkins and Lehigh around 1890. A Naval Academy professor, he coached Navy from 1904 to 1906, sat on the 1906 rules committee, and was a sought-after game official.

John C. Bell. Bell played football at Penn in the early 1880s before becoming a prominent lawyer and district attorney while also acting as Penn's athletic director and 1906 Rules Committee member.

James A. Babbitt. A Haverford professor and rule committee member, Babbitt's focus was on improving football's officiating.

Coaches

Four of the five coaches Camp considered most influential played at Yale, and three played under him.

George Woodruff. Stagg's teammate at Yale, Woodruff, had a 125-15-2 record at Penn from 1892 to 1901. His innovations included the guards back formation and onside kick from scrimmage.

Fielding Yost. Yost played at West Virginia and coached several schools before settling in at Michigan. His point-a-minute teams went 56 straight without a loss from 1901 to 1905.

Henry L. Williams. Williams played at Yale, and while a practicing physician, he turned Minnesota into a national power with his innovative shift offense.

Amos Alonzo Stagg. Stagg played at Yale and coached at the YMCA Training School before taking over at Chicago in 1892. He receives credit for double the number of his actual innovations, but he remains among the game's key innovators. Like Williams, he was a member of the 1906 Rules Committee.

Tom Shevlin. Shevlin played at Yale from 1902 to 1902. A Minneapolis native, he assisted Williams at Minnesota and others at Yale. Camp credits him with bridging the East and West.

Southern Man

William L. Dudley. While Dean of Vanderbilt's medical department, Dudley was deeply involved in the school's athletic program, drove the founding of the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association, and generally helped define Southern football.

Players

Pat O'Dea. An Australian, O'Dea moved to Wisconsin, joined the football team, and earned the "Kangaroo Kicker" nickname for dropkicking a 62-yard field goal and booting a 116-yard punt, among other kicking feats.

Walter Eckersall. A three-time All-American quarterback, Eckersall led Chicago to the 1905 national title with his speed, field generalship, and punting abilities.

Charles Dudley Daly. Daly played for three years and graduated from Harvard before enrolling as a West Point plebe in 1901 and playing for two more years. A talented athlete, Daly was a brilliant quarterback and kicker.

Captains

Arthur Cumnock. As Harvard's captain in 1889, Cumnock was the first to institute spring practice while inventing the nose guard (forerunner of the face mask) and the tackling dummy. (Stagg did the same at Yale that year.)

Truxton Hare. A four-time All-American guard at Penn, Hare called signals and handled kicking duties, with Camp claiming he could have been an All-American at any position. Hare was a silver medalist in the hammer throw at the 1900 Olympics and the 1904 gold medalist in the all-around event, the forerunner of the decathlon.

Given the organizational and rule-making turmoil football faced from the mid-1890s until 1912, it is understandable that Camp would weigh rule makers and administrators so heavily in his Top 20. More schools would likely have dropped had the game not addressed its issues. Rugby, which replaced football at key West Coast schools for a decade, could have challenged football for supremacy in the United States. Alternatively, the East Coast and the Midwest rule-making factions might have taken the game in different directions, leading to regional differences in game rules and eligibility standards. Had that happened, who knows what football's future might have been?

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.