Gather 'Round, Boys: A History of Huddling

Like life in general, there are elements of football that made no sense until someone started doing them; other elements made perfect sense until someone stopped doing them. Such is the case with huddling. Football did not need huddling initially because it served no purpose until teams had structured plays. Once the rule of possession entered the game, offenses lined up in consistent formations and used preplanned plays called at the line. Football at the time had a nearly continuous flow. One play ended, the offense lined up on the ball for the next play, called the signals, and snapped the ball. The rapidity of running plays did not result from rules requiring teams to do so but because teams had done so when playing rugby.

Huddling appears to have started in practices because teammates on defense understood the signals called by their teammates on offense. Most credit the first huddle on a game to Paul Hubbard, the quarterback at Gallaudet from 1892 to 1895. Gallaudet, a university for the deaf and hard of hearing, used American Sign Language (ASL) to call signals because they played most games against teams whose players were not hearing impaired. However, when Gallaudet played another hearing-impaired squad in 1894, that opponent understood Gallaudet's signals, so Hubbard had his team gather before each play. A few other teams huddled occasionally, but it was not until the 1920s that huddling became the norm.

H. W. "Bill" Hargiss appears to have had his Oregon State team huddle in one 1919 game. However, Bob Zuppke, who won four national championships coaching at Illinois, popularized the gatherings. Zuppke had the Illini huddle in the first game of the 1921 season, after which numerous teams copied the Illini "tea parties." For example, Navy's 1921 victory over Army was credited partly to their use of the huddle. It may seem odd to think of huddling as a strategic advantage, but Zuppke used it not only for communication purposes like today but also to gain an advantage once the team left the huddle.

Recall that many teams from the 1900s to the 1940s executed choreographed pre-snap shifts, often lining up on or behind the line of scrimmage before quickly shifting to overload one side or the other before the snap. Zuppke's teams caught defenses off guard by calling the play while huddled five yards behind the line, then quickly exiting the huddle, aligning, and snapping the ball before defenses could react to Illinois' alignment. Critics charged the Illini with gaining an unfair advantage by taking only a quick pause before the snap -the same criticism levied against teams that shifted pre-snap. At the same time, they derided huddling for slowing down the game, though studies showed huddlers snapped the ball as quickly as those that called signals at the line.

The criticism of huddling and pre-snap shifts led to a 1927 rule requiring players to stop for one second before the snap (extended to "at least" one second in 1930). The 1927 committee also established a rule of thumb that huddles should last no more than fifteen seconds, and the 30-second rule of thumb became a formal rule in 1939.

The rule changes limited huddling's surprise value. Still, the tactic stuck around for other reasons, and the huddles took different forms, so let's take a look at three primary forms of huddling that developed, along with an offshoot or two.

Closed, Circular, Ring, or Oval Huddle

From the beginning, Zuppke uses a closed huddle with the team forming a ring around their kneeling quarterback five yards behind the line of scrimmage. Others, like Jimmy Phelan's 1939 Pitt squad, formed a rectangle rather than a circle, but both accomplished the same objectives. A Zuppke saw it, huddles:

Blocked the crowd noise in the increasingly large stadiums, allowing his teammates to hear the quarterback

Allowed the team to settle down between plays

Enabled play calling in plain 'football English' rather than the codes needed at the line of scrimmage.

Snapping the ball shortly after getting into the formation limits the defense’s ability to spot the telegraphing of plays based on player stances and the like.

One of the more humorous aspects of these huddles was coaches who focused time and energy on keeping an orderly huddle and exiting it in a choreographed manner. For example, some teams had the center exit first, as if he needed extra time to bend over and grab the ball. Others had the linemen leave in serpentine fashion, one following another to the line of scrimmage. Even some NFL coaches worried about issues that contributed nothing to executing plays properly.

Of course, other coaches found the circular huddle lacking and approached the problem from a different angle.

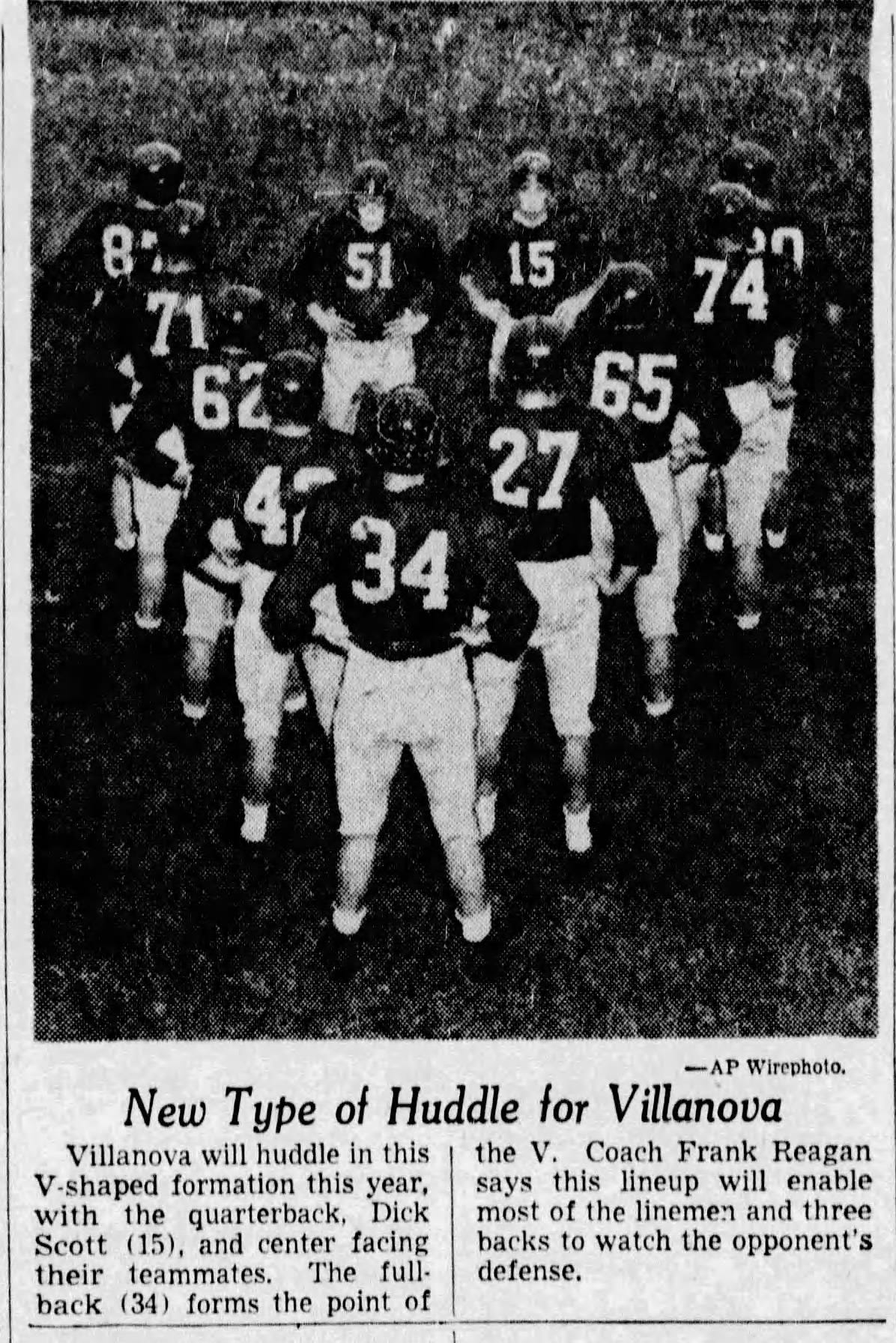

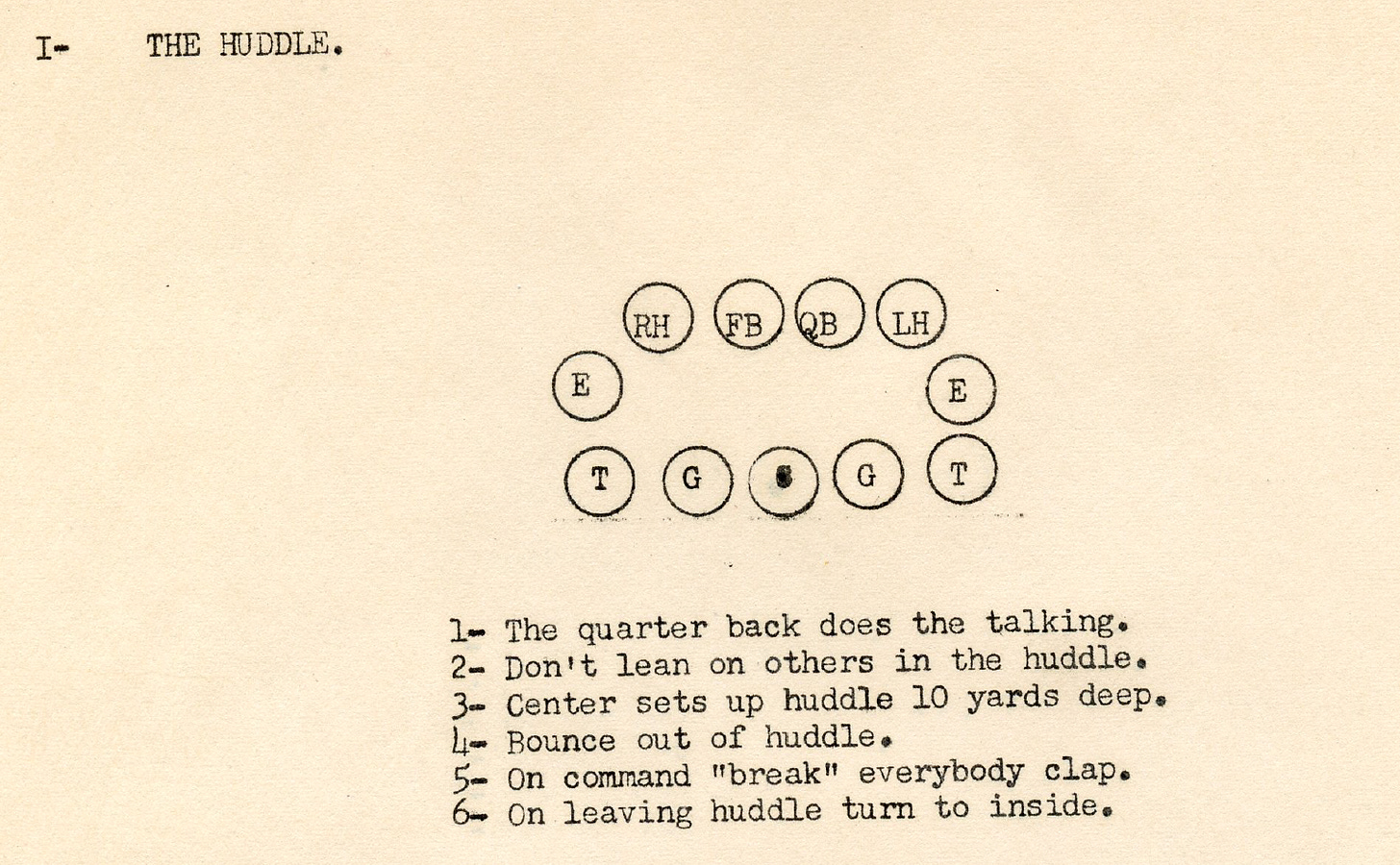

V or Triangle Huddle

One can only hope the inventor of the triangle huddle was a math teacher. The triangle huddle traces back to Bucknell in 1933. USC used it during the war, reemerging at Toledo in 1950, and its peak popularity came in the 1950s.

The V had the quarterback and center stand facing away from the line of scrimmage at the wide end of the V. The ends stood about five yards apart; the tackles were behind and closer than the tackles, followed by the guards, the halfbacks, and the fullback. The arrangement allowed everyone to see and hear the quarterback call the signals, and players moved from the huddle to the called formation with few wasted steps. It also had each player standing upright, allowing them to relax and catch their breath between plays. It also lets nine players view the defense from the huddle.

Looking to reduce the number of steps and with perhaps a bit less focus on orderliness, the third primary huddles format arrived in the 1940s.

Open, Typewriter, Family Portrait, or Classroom Huddle

Known by many names, the open huddle is, perhaps, the simplest and most relaxed huddling form. Typically, the interior linemen stand in a row, with the backs and ends behind them, while the quarterback stands before his teammates, facing them as he calls the signals. (Some teams have the quarterback face the defense, and others flip the huddle 180 degrees.)

Bo McMillan is supposed to have used the open huddle at Indiana in 1940, but I found no contemporary evidence of that claim. Most credit the open huddle to Tom Nugent, who used it as a Virginia high school coach before taking it to VMI in 1949 and Florida State in 1953, which was the freshman season for signal caller Lee Corso. (Nugent is also credited with developing the I formation in the early 1950s.)

Positioning of the players in levels led to this form being called the typewriter, family portrait, and classroom huddle. (You youngins' that never used a typewriter may not understand the reference.) Misinformed writers referred to it as the Notre Dame huddle after the Irish began using it in 1949. Regardless, the open huddle spread quickly in the 1950s, challenging the closed huddle for supremacy, but it likely did not attain that status until the 1980s.

No Huddle

As pointed out earlier, everyone ran the no-huddle offense when football began, so it is not as new as many think. Even ignoring its earliest form, teams that huddled sometimes went without huddling to catch defenses off guard. St. Mary's and other 1930s ran quick sets of scripted plays when they recognized a defense was lagging. Geneva College ran a no-huddle offense in the early 1960s, calling all plays at the line as in the old days. Other pro and college teams did so periodically.

However, the modern no-huddle became popular after Sam Wyche used it with the Cincinnati Bengals in the 1980s to limit the ability of defenses to substitute situationally. Subsequent rule changes that give defenses the time to match offensive substitutions have eliminated that rationale. However, the no-huddle still allows the offense to control the tempo while reducing the time and energy spent walking back and forth to the huddle, including during practices.

Of course, one of the criticisms of huddling when it emerged in the 1920s was that plays called in the huddle were sometimes not appropriate based on how the defense aligned. So, we have come full circle. Football has returned to calling plays at the line rather than in a circle to allow for better play calling.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.