George Varnell: The Walter Camp of the West

Four men have been called The Walter Camp of the West at one time or another. Amos Alonzo Stagg and Fielding Yost are well-known figures to most football fans, while the other two -Salem Goodale and George Varnell- are little remembered today. Of course, Camp was a player, coach, and team advisor who played a pivotal role in defining the rules of football. He was also the unchallenged journalistic voice of football for thirty of the game's formative years, writing weekly columns and naming All-America teams for Collier's Weekly. So, Camp's role in football's development did not derive from his exploits as a player or a coach but through his influence in other roles.

Like Camp, the four nominees played football when its eligibility rules were, shall we say, more flexible than today. Stagg played four years at Yale before becoming a full-time professor and head coach at the University of Chicago in 1892. Still, he acted as a player-coach for Chicago during his first year or two in the Windy City. Yost played baseball for three years at Ohio Northern before transferring to West Virginia. During his second or senior year there, Yost spent one Saturday afternoon playing as a ringer for Lafayette in their 1896 victory over Penn.

Salem Goodale captained Baker University in 1890, leading the Methodists to a victory over Kansas in the first college football game played in the state. After two years at Baker, he headed east, starring for Amherst for two years before landing at Occidental, where he played halfback while coaching their 1895 Southern California championship team. Goodale entered medical school a few years later, leaving the football world behind him.

Why someone viewed Goodale as the Walter Camp of the West is a bit of a mystery, and Yost, while a highly successful football coach, had a narrower impact on the game than Stagg. Stagg certainly is a contender for the title, serving as the first Western Rules Committee member and a college coach from 1890 to 1946. But let's take a few minutes to consider George Varnell and his worthiness for the WC of the W title.

George Varnell's early years paralleled those of Stagg, Yost, and Goodale. Varnell's father, a lawyer, died when George was eight years old, resulting in George living above his brother's saloon with his mother, grandmother, siblings, two servants, and four boarders. Varnell appears to have skipped school for a few years before graduating from high school at 21 in 1904.

That summer, St. Louis hosted a World's Fair and Olympic Games, in which participants represented themselves or their clubs rather than their countries. The majority of competitors were Americans, Canadians, or workers from the World's Fair. Varnell, whose high school track times proved he was a national-level runner, represented the Chicago Athletic Club, placing fourth in the 200- and 400-meter hurdles. Some shine comes off those achievements, given that only five and four runners participated in those races, respectively. Nevertheless, he was a top-level hurdler.

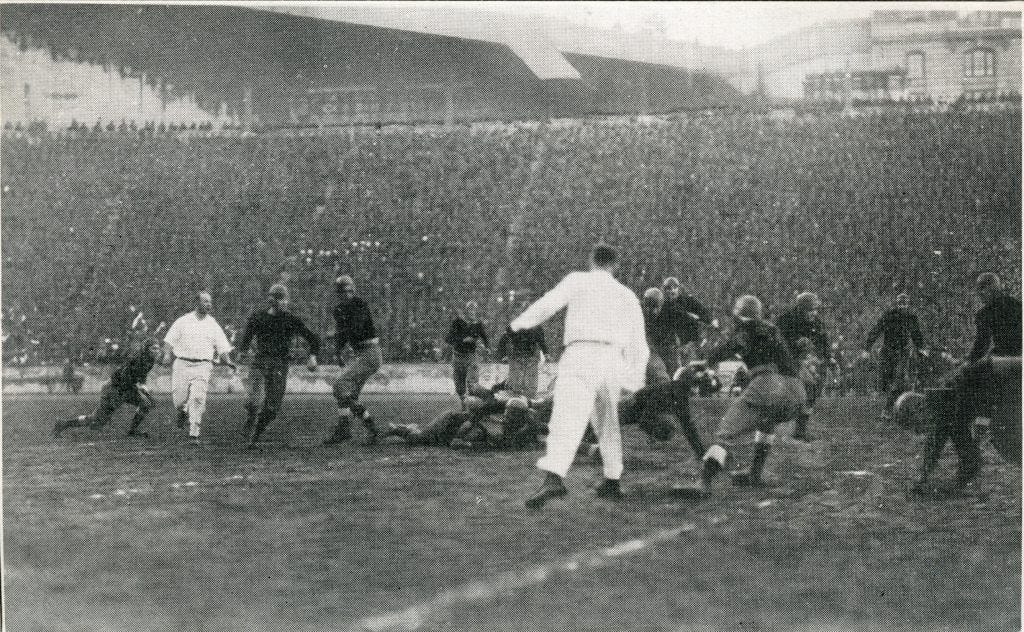

Upon returning home, Varnell joined Amos Alonzo Stagg's University of Chicago Maroons. Varnell was part of a backfield that included fullback Hugo Bezdek, who later coached three different teams in the Rose Bowl, and Walter Eckersall, then in the first of his three seasons as an All-America quarterback, leading Chicago to the national championship the next year. Varnell was a sub for most of the 1904 season but started and scored six touchdowns in an early-season game against Englewood High. Unfortunately, he flunked out after the first term and began looking for a new home.

The 1905 season found Varnell playing at Kentucky University, now Transylvania, which became Kentucky's football power of the time by stretching the Bluegrass State's liberal academic and compensation standards. On one weekend trip that season, Kentucky University beat Texas and Texas A&M on back-to-back days, and Arkansas two days later. Varnell was one of four players accused of being ringers around that time, precipitating a series of investigations over the next few months.

Varnell showed up in Spokane in 1907 as the Physical Director for the Spokane Amateur Athletic Club. He organized, coached, and played on their teams before taking a similar role at Gonzaga. While at Gonzaga, Varnell restarted the football team, going 10-4-1 over four seasons. Varnell often coached the team during the week but had others manage the team on game days since he was busy refereeing other college games. During his last two years coaching Gonzaga part-time, Varnell became the Spokane Chronicle's sports editor. Covering games in his role with the press and as an official enabled Varnell to name the All Northwest and All Pacific Coast teams, which became the de facto all-star teams for the West Coast.

While it was not unusual at the time for sportswriters to officiate games they covered for their newspapers, and some coaches officiated games during bye weeks, Varnell managed to do all three. Varnell also refereed top college basketball games, was the starter at high-profile track meets in the Northwest, and officiated crew regattas. Still, he was best known for his work on the gridiron. Starting in the mid-1910s, Varnell refereed key games on the West Coast, including the 1917 Mare Island-Camp Lewis regular-season game that previewed their rematch in the 1918 Rose Bowl.

After the war, Varnell officiated every Rose Bowl between 1920 and 1926 and had a return engagement in the 1937 game, a record of eight Rose Bowls that remains unmatched. (His string working the Rose Bowl during an era in which it was the only post-season game of consequence is particularly noteworthy.)

Varnell's position among the football elite was recognized in 1924 when he was named to the college football rules committee as its West Coast representative, serving in that capacity for six years, the first two of which overlapped the tenure of Walter Camp. None of the rules made during his time on the committee were monumental, though a favorite rule change was the decision to consider a fumble out of bounds to be a dead ball. Previously, balls fumbled out of bounds were live, leading to mad dashes into the bench, over water jugs, and among spectators by players seeking to recover the ball.

Varnell's calls as a referee did not escape controversy. Though unrecognized in the moment by the teams, scoreboards, and sportswriters, Varnell ruled in the 1925 Big Game that California was offside when it blocked Stanford's final extra-point attempt. Since the rules of the day awarded a point to the kicking team when the defense committed a penalty on an extra point attempt, Varnell awarded Stanford the point, making the core 27-14 rather than the 26-14 score everyone else reported. That and other controversies led to Varnell being blackballed from the Big Game for several years, but cooler heads prevailed, and Varnell soon returned to working the game. He also refereed the 1927 Notre Dame-USC game at Soldier Field that drew 120,00 fans. The game was the second between the two teams and USC's first game east of the Rockies.

In the mid-1920s, Varnell left Spokane to become the sports editor at the Seattle Times. Working from Seattle during a time when the West Coast lacked high-level professional sports, Varnell covered the University of Washington sports, particularly its football and rowing teams. Washington played in one Rose Bowl during the period, a performance Varnell deemed underwhelming, leading to public battles with the Huskies coach, Jimmy Phelan. Varnell stopped officiating Washington football games but continued reffing PCC and other games into the mid-1940s. Varnell retired from officiating in 1946, having handled more than 800 games during his time as a whistler,

The high point of his Washington crew coverage came when they traveled to the East Coast in June 1936 for several regattas, during which they earned the American berth for the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. After learning the team needed to fund the trip themselves, Varnell and another Seattle editor publicized their plight, leading to a fundraising campaign that financed the trip. The Olympic gold-medal-winning team's story was popularized in recent times by Daniel James Brown's, The Boys in the Boat.

Varnell shifted into semi-retirement in the early 1950s as a columnist and occasional commentator on gridiron topics. In a refereeing and writing career that spanned forty years, Varnell was on the field for many big games of that era, and his reporting influenced how many on the West Coast understood the game. Did he influence football to the level of Walter Camp? No. But Varnell's multiple roles likely resulted in a greater impact on football in the Northwest than any coach or other individual involved in the first one hundred years of the game. Perhaps he comes as close as any other individual to having earned the Walter Camp of the West appellation.

Click here for options on how to support this site beyond a free subscription.