Head, Shoulders, Knees, and Toes: Football Equipment Safety Standards

Football’s early rules said little about the equipment players could or should wear, mainly because players wore only light jerseys, tights, and caps. American football’s first rules of 1876 were copied nearly word-for-word from the 1876 Laws of Rugby. It had only one rule concerning player equipment, borrowed from the Football Association (soccer) rules of the 1860s.

The 1876 Intercollegiate Football Association rule 58 read:

No one wearing projecting nails, iron plates, or gutta percha on any parts of his boots or shoes shall be allowed to play in a match.

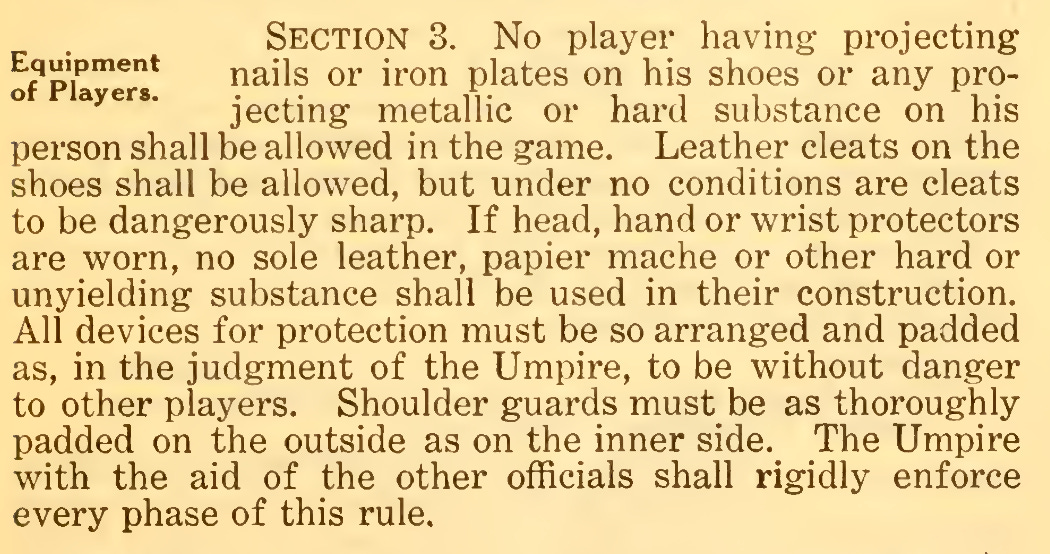

After a team or two had greased their uniforms to make them harder to tackle, the rulemakers banned sticky, greasy substances. Then, as players began wearing protective equipment in the 1890s, the prohibition on nails and iron plates extended beyond shoes to cover the entire body.

No one having projecting nails or iron plates on his shoes or wearing upon his person any metallic or hard substance that in the judgment of the referee is liable to injure another player, shall be allowed to play in a match. No sticky or greasy substance shall be used on the persons of the players.

Spalding’s 1900 Official Foot Ball Guide

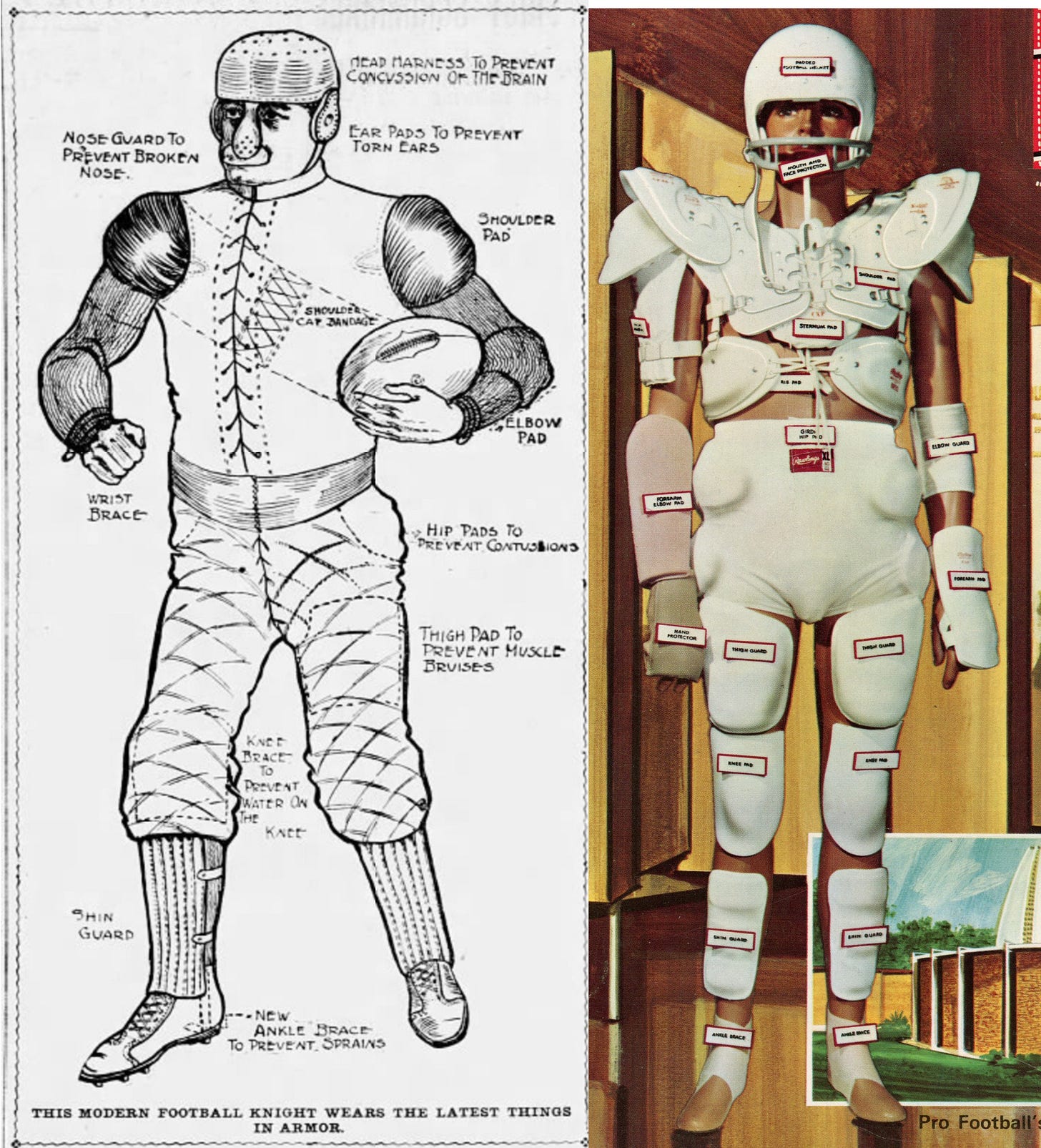

While the rulemakers banned specific equipment, they did not require players to wear anything in particular. They took the laissez-faire stance that players had the right to bare arms, heads, and other parts of their bodies. But as sporting goods manufacturers increasingly offered equipment to protect all parts of players’ bodies, players began to adopt that gear, and the rulemakers extended specific prohibitions, but still did not mandate gear.

The ongoing challenge for the rulemakers was that the equipment most protective of the wearers often used hard, unyielding materials that could endanger other players. They tried to address the issue in 1924 by requiring padding on both the inside and the outside of equipment. Knee and thigh pads largely conformed to that standard, but there were no shoulder pads on the market with exterior padding, so everyone ignored the rule except for egregious violations. Hip pads often had rigid exterior plates as well, though few suggested they led to injuries.

The 1930s saw the high schools and pros adopt rule books separate from the NCAA’s. Another key shift came as governing bodies began recommending, and later mandating, the use of protective equipment. High school equipment safety standards generally preceded college standards by a year or two, and the NFL trailed both.

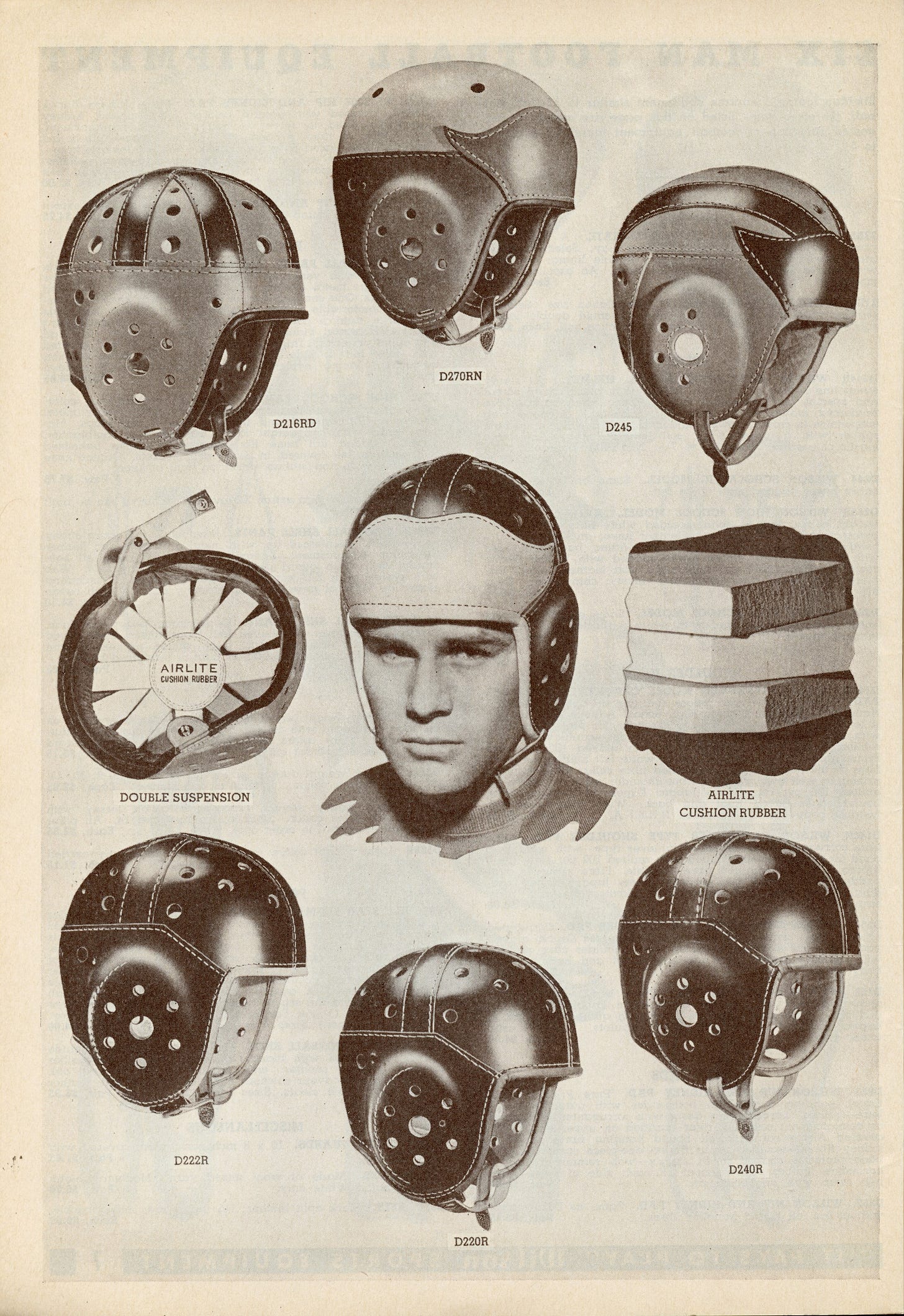

The NCAA’s 1932 rules recommended that all players wear soft knee pads, not to protect the wearers but to protect the tacklers and others who an unpadded knee might strike. They mandated their first safety-related equipment in 1939, requiring players to wear soft knee pads and head protectors (aka helmets). Ironically, plastic helmets arrived the following year, sparking a 20-year debate over the safety benefits of leather versus plastic. Meanwhile, the high schools mandated helmets in 1935, and the NFL followed suit in 1943.

Although some players wore leather helmets with face masks, face mask use grew as plastic helmets became more popular. The NFL required face masks in 1955, but did not make facemasking illegal until 1962. High schools and the NCAA made facemasking illegal in 1957. Oddly, the NCAA did not require face masks until 1993, when they argued both that it was an oversight and that the rule was unnecessary since everyone already wore a face mask.

Continuing with head and facial safety, the high school rules mandated mouth guards in 1962, with the NCAA following ten years later. Other NCAA helmet and head-related requirements included the requirement that helmets be NOCSAE-certified in 1978. The NCAA also recommended that players wear four-point chin straps in 1975 before requiring them in 1996.

While football’s first equipment rule focused on players’ shoes and cleats, there have been few subsequent shoe-related rule requirements. Early rules concentrated on the length and sharpness of the cleats. Then, the NCAA approved rubber detachable cleats in 1927 and limited cleat length to 1/2 inch in 1972, a limit that remains in place today.

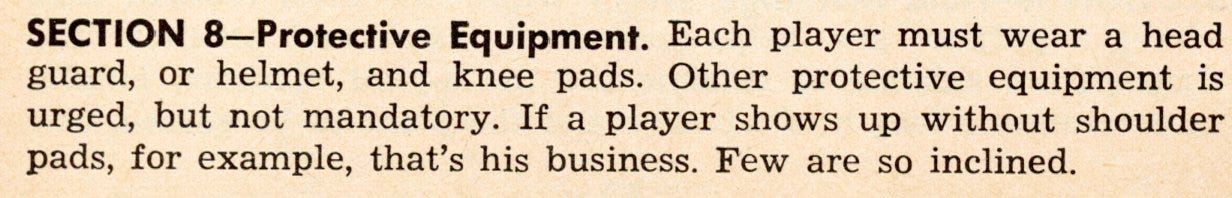

So, for many years, the NCAA mandated only head protection and knee pads. They exemplified their laissez-faire approach toward other pads in the 1970 “Read-Easy” version of the rules, noting that shoulder pads are not required, but only fools would rush in without them:

Despite their smarty-pants attitude, they mandated shoulder pads in 1974. Hip pads with tailbone protection came a few years later. After adding the face mask requirement in 1996, the list of required equipment has not changed. The 2025 NCAA Rule Book mandates only a few pieces of protective equipment, followed by several pages of equipment specifications that mainly focus on aesthetics rather than function.

So, the list of mandated equipment is relatively brief, the quality of the equipment has improved dramatically, as have playing conditions, training and medical standards, and playing rules that prohibit dangerous elements of the game.

With the holidays approaching, now is the time to add one or more of my books to your holiday list. Make yourself and others merry.

I assume that the current fad, if you will, of abbreviated thigh pads and bared knees and legs means that players' injuries or 'Ow's in those areas are either minimal or not felt ..