How Football's Zebras Got Their Stripes

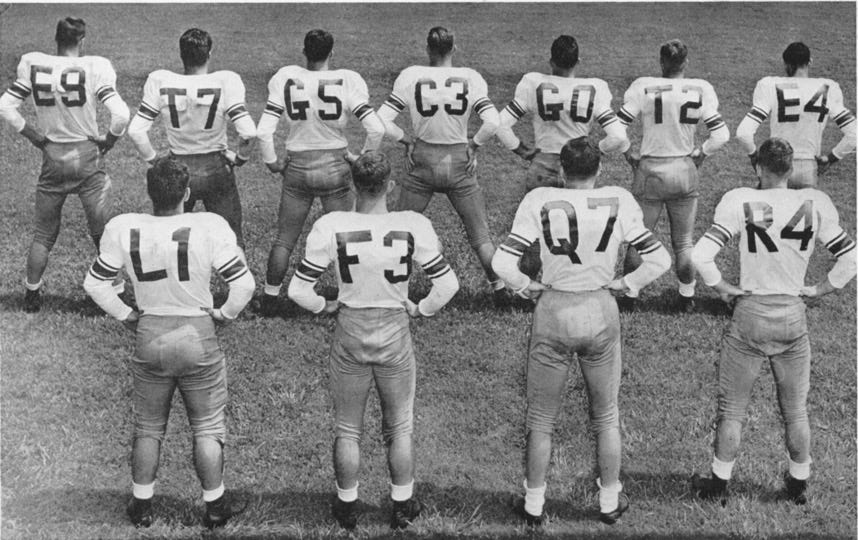

It is easy to see football today and think the game’s evolutionary path was inevitable, but there is nothing pre-ordained about today’s game. Football might have taken any number of alternative paths, and often did, though many of those twists and turns are forgotten today. Consider that American football was played on a field with a 55-yard line and no end zones until 1912. Only the tweaking of the rules of the recently allowed forward pass led to the adding of end zones and the elimination of the 55-yard line. Likewise, the first wearing of numbered jerseys came in 1905 when rivals Drake and Iowa State met. Drake wore numbers between 1 and 25; the Cyclones wore 26 to 50. As numbered jerseys became popular, players were not numbered by position. Even when the NCAA mandated that player numbers correspond to their position, there were multiple systems proposed, including alphanumeric combinations tried by a handful of schools.

The point here is that many changes in the game arrived half baked, were opposed by one faction or another, or benefited from a bit of fine tuning. And that brings us to the black-and-white striped shirts universally worn by football officials today. As I wrote in How Football Became Football, early football officials did not have uniforms; they wore everyday clothes. Many chose to wear older pants and jackets due to the need to keep pace with the players running around the field, as well as the muddy conditions of many football fields of the day. Besides everyday clothes, many officials wore their college letter sweaters during games. Letter sweaters marked the officials as authorities on the game and reinforced their neutrality since they generally did not work games involving their own college or schools for which they were associated. (Pre-WWII newspaper box scores typically listed the officials working the game and their alma maters.)

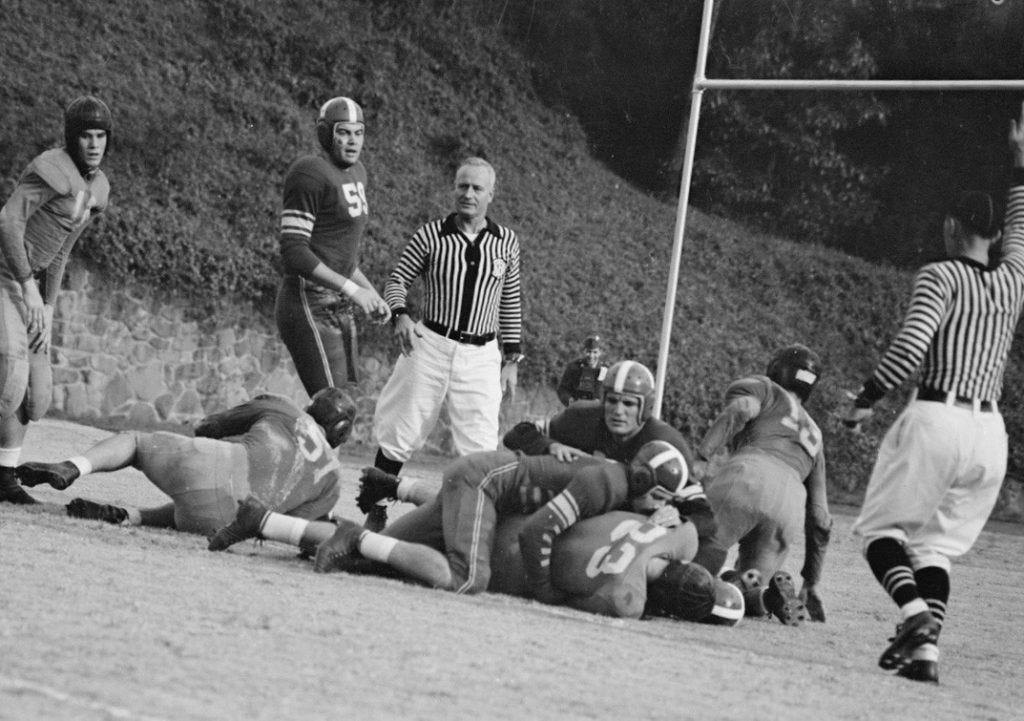

In the 1910s, basketball officials began wearing white shirts and bow ties during games. That practice leaked over to football, particularly among officials on the West Coast, where warmer weather allowed officials to handle games in their shirt sleeves. Although officials wearing white shirts became widespread, it coincided with the emergence of teams wearing white jerseys. (As described in an earlier article, the white jerseys of the Twenties and Thirties were fashion choices unrelated to the 1950s trend of the visiting team wearing white jerseys.)

The wearing of white by football officials became a norm in the early 1920s, but Lloyd W. Olds, a professor and track coach at Eastern Michigan, grew frustrated when officiating football and basketball games because players whose teams wore white jerseys regularly tossed him the ball, mistaking his white shirt for a teammate’s jersey. To remedy the situation, Olds asked a local sporting goods store to create a shirt unlike any worn by football and basketball teams of the time. The result was the black-and-white, vertically-striped officials’ shirt that became known as the zebra shirt.

Officials in football and basketball picked up on Olds’ idea and the zebra shirt’s use spread organically. During the same period, high school officials at the state level and college officials at the conference and regional level organized to facilitate the training and scheduling of officials. As part of their efforts to standardize the quality of officiating, some state associations adopted the zebra shirt in the early 1930s and the Big Ten made it official for the 1937 season.

We all know that the black-and-white striped shirt became the standard officials’ shirt for football, basketball, wrestling, and hockey, so you might think the story ends there, but it does not. Nope. In fact, the zebra shirt had regional competitors that might have emerged as the standard nationwide, but the alternatives fell off one by one for reasons that are unclear.

Down in the Southern Conference, which in the early 1930s included the core of the today’s Atlantic Coast and Southern Conferences, the Southern Football Officials Association (SFOA) took a different route. Rather than adopt the increasingly-popular zebra shirt, the SFOA opted for a white shirt with a black collar and stripe down the shirt’s front zipper. The SFOA logo over the left breast topped off the ensemble. The SFOA’s shirt came into use in 1932 -five years before the Big Ten adopted the zebra shirt- and remained the standard until 1941. Since the Southeastern Conference also used SFOA officials during the period, all major college games in the Deep South had officiating crews clad in these outfits.

By 1941 the SFOA appears to have recognized their shirts did not stand out sufficiently, but opted not to switch to the standard zebra shirt. Instead, they adopted a zebra-like shirt with one-inch vertical stripes on the torso and one-inch horizontal stripes on the arms. The 1941 shirt was, in a word, an abomination, leading the SFOA to surrender and adopt the standard zebra shirt by the late 1940s.

After switching to the standard zebra shirt, the SFOA made one lasting contribution to officials’ outfits in 1949 when they added patches with letters on the zebra shirts to designate each official’s role in the crew. The letter R designated the referee, U stood for umpire, L for head linesman, and J designated the field judge.

You might think alternatives to the zebra shirts ended there, but you would be wrong. Returning to the late 1930s, but heading further west, the officials handling Southwest Conference games also created a zebra alternative shirt. It seems that the Southwest Conference Officials Association (they also used the SFOA initialism, but we'll refer to them as the Southwest Conference officials) wanted to grow its membership to enhance officiating standards and quality. At a time when many officials in the area had adopted zebra shirt, Abb Curtis, the head of the officials association, designed a shirt with V-shaped stripes on the front and back. By trademarking the design and allowing it to be worn only by members, the Southwest Football Officials Association distinguished its qualified members from the rabble wearing white or zebra-striped shirts. (The Lake Charles Football Officials' Association in Louisiana used a V-striped shirt starting in the early 1930s, but is not known whether their shirt influenced the Southwest Conference design.)

Unlike the SFOA folks that switched to the zebra shirt in the late 1940s, the Southwest Football Officials Association kept their V-striped shirts through the 1940s, and the 1950s, and most of the 1960s, before adopting the zebra shirt for the 1968 season. One can only speculate on the reason for the switch, but it followed soon after Abb Curtis' retirement as head of the conference officials in 1967. Given that Curtis designed the V-striped shirt and headed the organization for many years, the V-striped shirt may have remained in use due to the members' respect for Curtis.

A final note about the mix of shirt designs worn by football officials concerns the impact of multiple shirt designs on nonconference and bowl games. Prior to 1991 when the NCAA prohibited split officiating crews, games involving opponents from different conferences often had split crews manned by officials from the two team's conferences. That led to at least one officiating crew wearing mismatched uniforms, though most period images show split crews overwhelmingly wearing zebra shirts, perhaps to avoid drawing attention to each crew members' conference affiliation.

The road to football officials consistently wearing the black-and-white striped shirt had multiple twists and turns, and this article did not even cover the various professional leagues experimenting with stripes in all colors of the spectrum. Still, it took sixty years of football before Lloyd Olds recognized the need and dreamed up the striped shirt and almost another half century before all college officials were consistently attired.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.