Image Breakdown: The 1893 Penn-Cornell Game

Sports historian Matt Bufano recently posted a great image from the 1893 Penn-Cornell game. I thought the image was worth digging into since it illustrates many differences between football then and now.

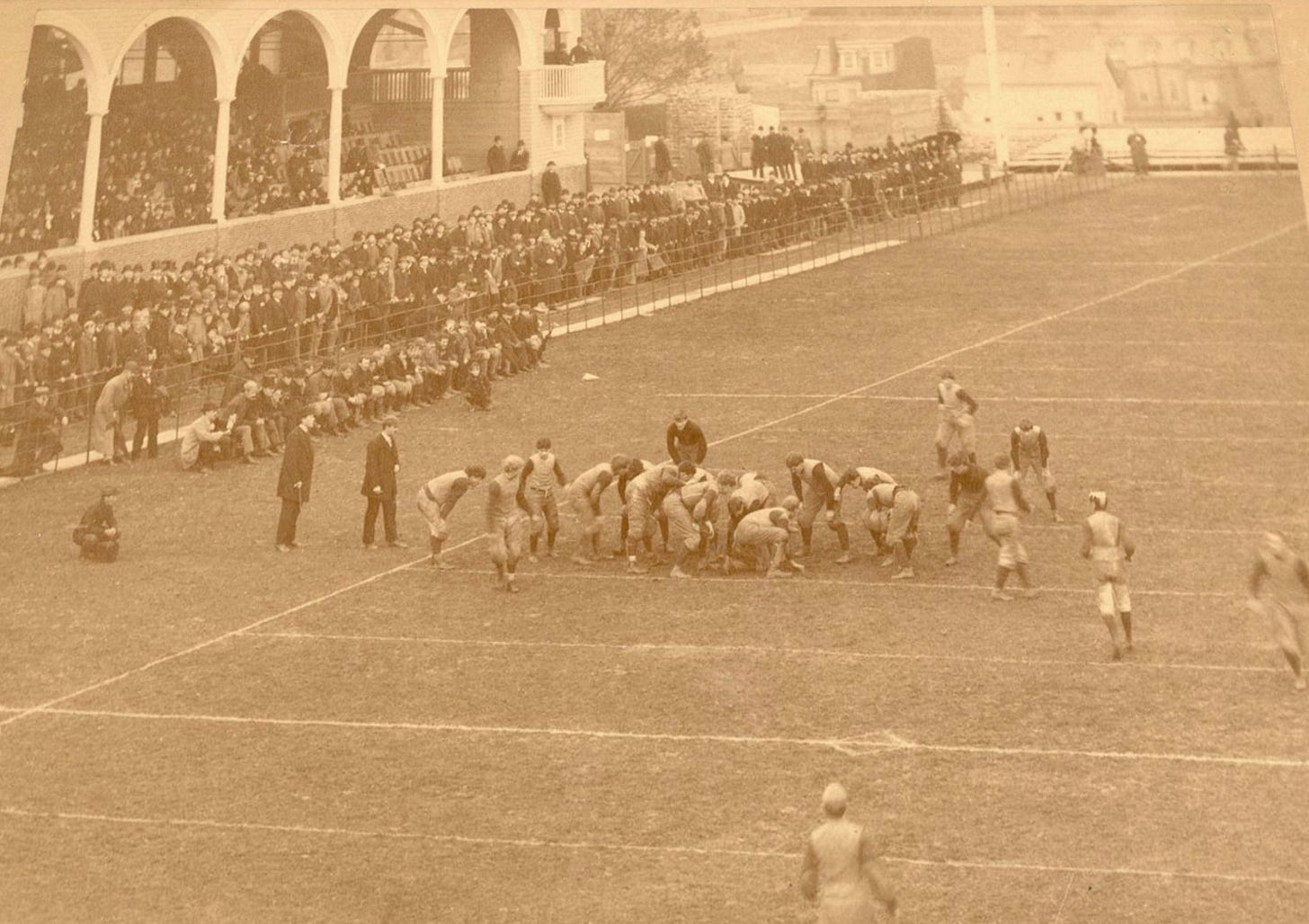

Sourced from the University of Pennsylvania Archives, it is unusual for being a game-action image shot from a height behind an end zone, akin to today's All 22 film. The image includes one's team bench and a portion of the 4,000 fans watching the last home game of the season on a cold, rainy day at the Manheim Cricket Grounds in the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia.

Cornell started the season 3-0 before earning one tie and five defeats. Penn, meanwhile, started the season at 11-0 before falling to Princeton and Yale. Penn expected an easy win, while Cornell hoped for the best.

A lot is going on in the image, so I'll break down what I see in the picture, and a few items picked up from the newspaper reports of the game. As a teaser, I'll point out that the game involved three men who coached a combined 602 college football wins in their careers. There were others involved in the game who had less stellar coaching careers and whose wins were not included among the big three.

Penn's first-year coach, George Woodruff, tallied one of the 602 wins that day by leading the Quakers to a 50-0 victory over Cornell. (The image description incorrectly lists the score as 53-0.) Woodruff, who notched 142 wins in his career, is the last guy on the left side of the bench wearing the light-colored hat. The guy sitting to his left wears a top hat, something not seen on a football sideline for a long time.

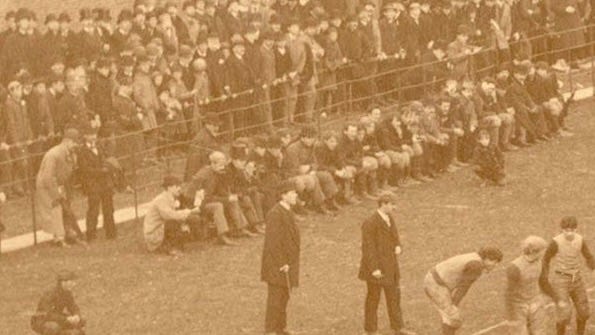

Everyone along the sideline is seated on the bench or kneeling while the crowd sits in the grandstands or stands behind the ropes. In those days, ropes often separated the crowd from the playing field, so football's official rules sometimes mentioned the people “behind the ropes” when referring to spectators.

According to newspaper reports, Cornell wore bright red sweaters, while Penn had red and blue striped jerseys and sleeves. Although the image is brown-and-white, we know Cornell is on offense, farther away from the photographer. Zooming in reveals the striped sleeves Penn wore that year.

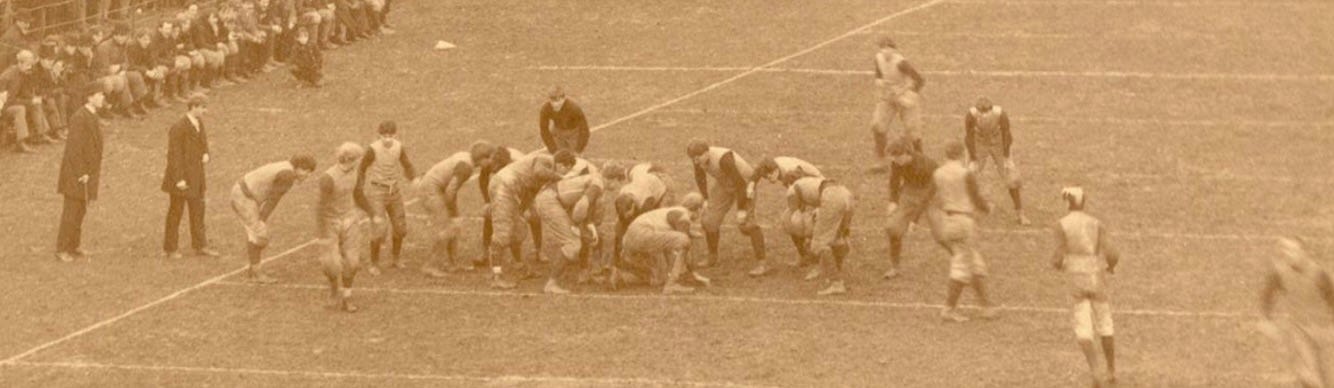

Another confirmation that Cornell is on offense comes by looking at their left guard. He's the biggest guy on the field and is listed in Cornell's team picture as G. S. Warner, aka Glenn Scobey or Pop Warner. He won 319 college games during his coaching career.

The scrimmage occurred close to the sideline since the previous play ended there, and football did not add hash marks for another 39 years. We see Cornell preparing to punt with the fullback, the punter, set deep. The center bends over with his hands on the ball, which was a new technique in 1893 since centers previously snapped with their feet, as in a rugby scrum. Long snapping did not yet exist, so the quarterback bends over behind the center to receive the snap, planning to lateral the ball to the fullback. Several Penn players are dropping back to help block on the punt return and ensure that Cornell does not execute a QB kick or onside punt play.

The largely barren field has some interesting markings, including some I had not seen before. Note the diamond chalked on the yard line ten yards behind the Penn line. Diamonds or similar markings appeared on the 25-yard lines back then to indicate the limit for kickouts following a touchback or safety. (Teams kicked from the 25 following both plays, just as they punt from the 20 after a safety nowadays.)

The diamond marking was helpful since fields did not have yard line numbers painted on them, nor did they have field markers along the sidelines or painted on the walls of the bleachers, so the yard lines all looked alike. Note, however, that the 25-yard line extends on the left past the sideline. In addition, the yard line extends past the sideline at the 55-yard line, which is 10 yards behind the offensive fullback, as does the other 25-yard line 30 yards further back. I assume the extended stripes helped the officials, players, and fans identify the ball's position on the field, besides noting the spots for kickouts (the 25-yard lines) and the kickoff (the 55-yard line).

Also, note how close the offensive and defensive players are to one another on the line of scrimmage. Football had no neutral zone until 1906, so players on both sides often overlapped the ball. The 1893 season was also the last in which defensive players could interfere with the center's snap by hitting the ball when the center began his snap. As noted in the past, the offensive players next to the center received their position name because they "guarded" their teammate, especially if you were Pop Warner's size. Also notable is the Penn player over the center, who is in a three-point stance, which was unusual for the era.

While the extended stripes were an excellent addition to the field, football did not yet have the chains and down box; the chains were invented in 1894. The two guys standing out of bounds at the line of scrimmage are the referee, Dr. W. H. Brooke of Harvard, who stands closest to the sideline, and the umpire, Henry L. Williams, an 1890 Yale graduate who coached Army in 1891 and was the coach at Philadelphia’s William Penn Charter School in 1893. He won five games coaching Army, including their first victory over Navy, and later had a 22-year stretch at Minnesota, where he won another 136 games.

As for the game itself, Penn dominated throughout, though they nearly allowed a Cornell score in the second half. Three of Penn's touchdowns came by the running of Win Osgood, who played four years at Cornell before transferring after the 1892 season to play two more seasons for Penn. Osgood earned fame the week before the Cornell game with a touchdown against Yale, the first score on Yale in three years. (A Floridian, Osgood volunteered to fight for Cuba in their battle for independence from Spain and was killed in action in 1896.)

Penn's domination was such that the teams shortened the second half from 45 to 25 minutes. Despite outclassing Cornell on the field and having lots of players on the bench, the box score shows the Quakers subbed only three players into the game, one of them due to injury.

Cornell finished the season 3-6-1, while Penn lost to Harvard the following week to finish 12-3. Notably, Penn went 67-2 the next five seasons, with three undefeated national championships to their credit.

I'll try to find other old-time images to break down since pictures speak louder than words alone. If you have an old-time image that needs breaking down, comment below or post it to Twitter and copy me.

If you enjoyed this post, you might like my breakdown of the 1903 Princeton @ Yale game film...

... or the look at the Polo Grounds field for the 1903 Penn-Columbia game.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.

Alden Knipe (left halfback, Penn) coached at Iowa from 1898 to 1902, won 29 games, and tied for the conference championship in 1900, the first year that Iowa was in the conference. He had a medical degree and was an opera singer, but he quit coaching to write childrens' books with his wife.

Amazingly that field is still there and I believe still used for cricket. Google maps shows it with 21 lawn tennis courts!