Inflating Footballs, the Adjacent Possible, and Progress

We all know how to inflate a football, basketball, soccer ball, or volleyball. You lubricate the inflation needle with a bit o’ spittle, insert it into the black rubber button on the ball’s side, and then pump in air until the ball reaches the desired inflation level. It is a simple process and has been so for nearly 100 years.

But things were not always so. Until the mid-1920s, balls lacked those little black buttons, so you had to unlace the ball to inflate it. Footballs began as inflated animal bladders, but since the bladders did not withstand many kicks, they placed them inside leather bags sewn tight with leather laces. When the bladder broke or leaked, they unlaced the ball and replaced or reinflated the bladder.

Rubber bladders came along in the 1800s, but, like their animal forefathers, they had stems that were inflated by mouth, like a child’s balloon. After tying off the stem, they stuffed it inside the leather cover, laced the ball, and got back to kicking.

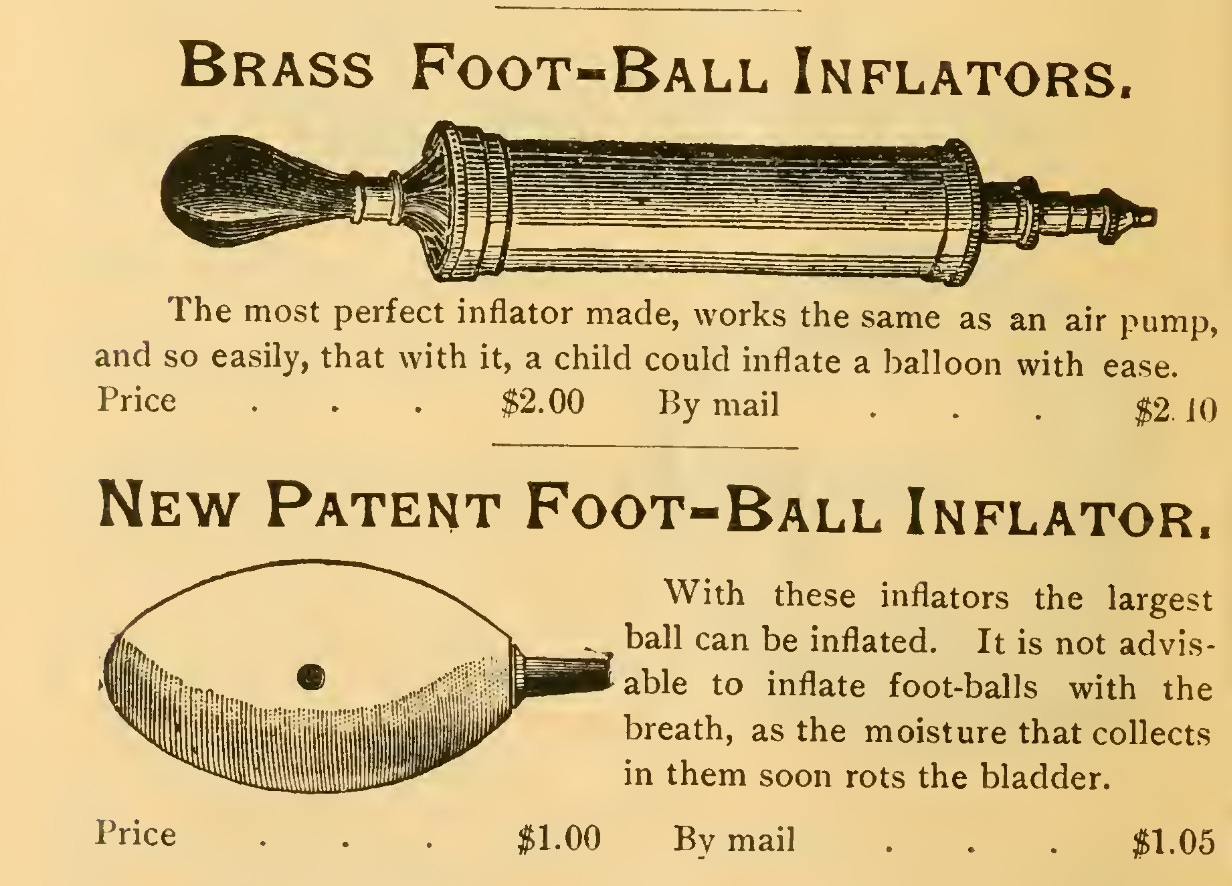

Hand pumps soon assisted the inflation process, but the stems still had to be tied until the early 1920s, when they finally inserted metal valves into the stems. The early football valves were much like those on today’s bicycle tires. They reduced leakage, and you still had to unlace the ball to access the valve.

Ironically, veterinarian John Dunlop invented the first pneumatic tire in 1888 when he wanted to provide his son a smoother tricycle ride. He devised a tire using surgeon’s rubber and the rubber stem from a football, which he inflated with a football hand pump. So, what goes around comes around in the world of inflation.

The need to regularly unlace and lace the ball was an accepted part of ball ownership. The regular lacing of balls required flexible, narrow laces, much like the rawhide lacing used on baseball gloves. The small laces helped basketballs bounce more consistently, but it reduced the torque passers generated when throwing overhand spirals.

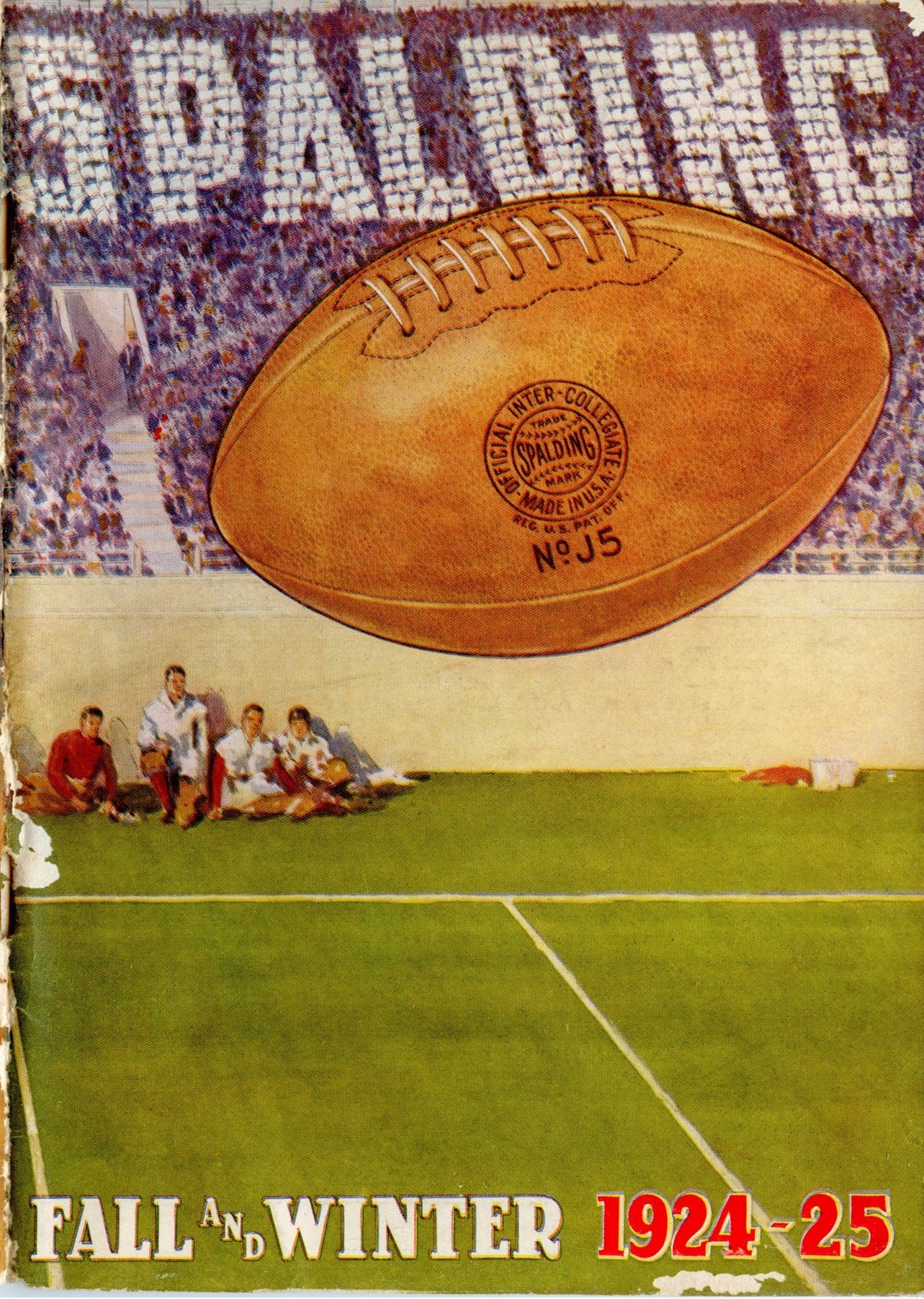

These and other issues are covered in A History of the Football, which traces the evolution of the football’s materials, construction, and appearance from its rugby origins to the ball we use today. Having written that book, I suspect I have investigated the ball’s historical trajectory as thoroughly as anyone. Yet, I learned something new last week when I acquired the 1924-25 Spalding Fall and Winter catalog, which has the beautiful Spalding J5 on the cover.

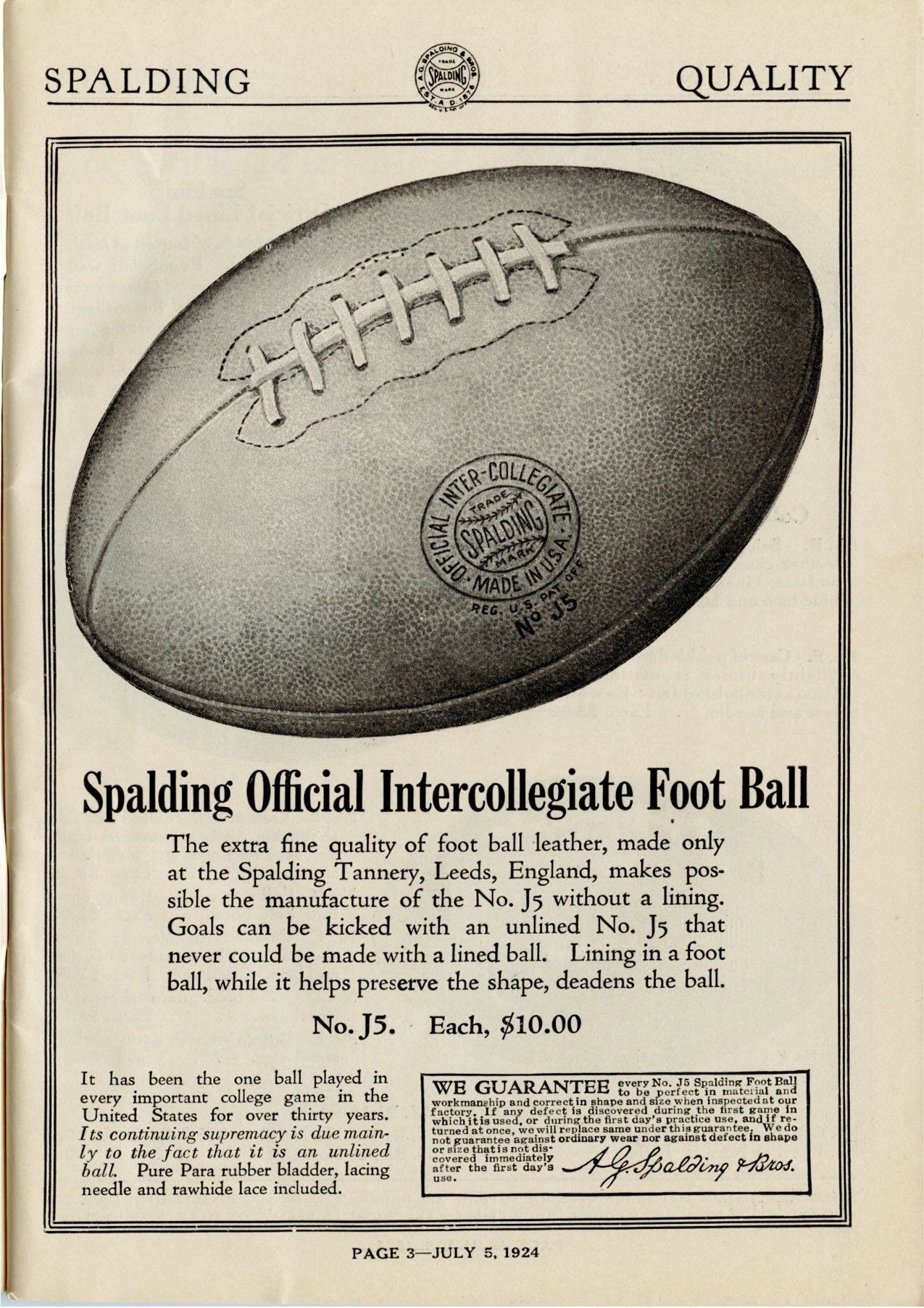

Despite All-Americans carrying the J5, Spalding made them of English leather. More important, as the note in the bottom left corner of the following page informed potential buyers, Spalding boxed and shipped the balls unlaced, accompanied by a length of rawhide and a lacing needle. Customers laced them before their first use.

One of the most significant changes in the history of the football came in the 1920s with the invention of a smaller, lighter valve that sat flush with the bladder’s surface. I previously assumed that when they introduced the new valve, it sat flush with both the bladder and the ball’s leather cover, so the valve was accessible from the ball’s exterior. With the valve accessible from the exterior, people could finally inflate balls without unlacing them.

Silly me. Page 5 of the 1924-25 catalog shows Spalding did not move directly to Go and collect $200. Instead, they took an intermediate step. Rather than making the valve flush with the leather, Spalding positioned the valve in the same spot as the stem valve -under the laces. Customers still had to unlace the ball to access the valve, so they saved a little time, but it took more work than is required today.

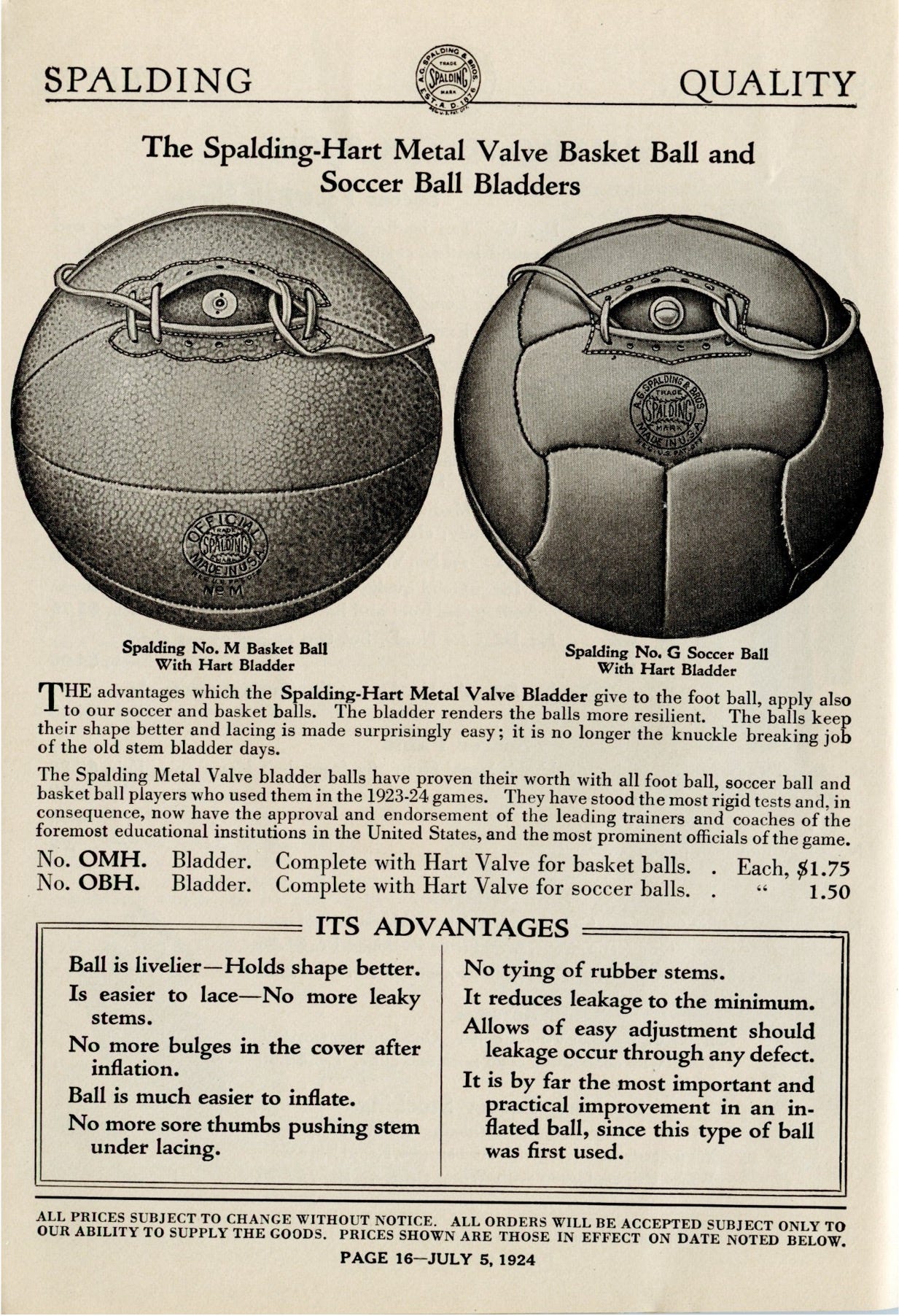

Spalding did not discriminate against footballs; they took the same partial approach with their basket and soccer balls.

Why would they do such a thing? There are several potential reasons for not taking the Great Leap Forward. Apparently, the first version of the valve was not designed to sit flush with the leather, so it took time and expense to adapt the valve to function differently. Spalding may also have needed new manufacturing technologies, leading to a partial improvement in 1924.

Another explanation is that no one thought to make the valve flush with the leather in 1924. Having the valve flush with the leather is the obvious solution to us now, since that is how everyone has inflated balls since before we were born. But they lacked that experience and perspective in 1924, so they went from Step A to Step B, then to Step C in 1926.

Taking intermediate steps toward complete solutions is common in football and in life generally, as Stuart Kauffman’s concept of the adjacent possible explains. Kauffman, an evolutionary biologist, argues that systems expand or evolve in small, adjacent steps. Similarly, while the universe of human knowledge, skills, and technologies is ever-expanding, human systems evolve one step at a time.

Just as wolves did not become dachshunds overnight, the flush valve needed a few years before football designers could create a dramatically improved ball. In 1926, Spalding introduced a ball with the flush valve projecting through the leather, which they called the J5-V. Still, they sold basketballs and soccer balls with laces for several more years, even though the laces no longer served a purpose in those sports. Some argued for eliminating the laces on footballs as well, but they stuck around, becoming stiffer and taller, since more prominent laces helped passers generate more torque on the ball.

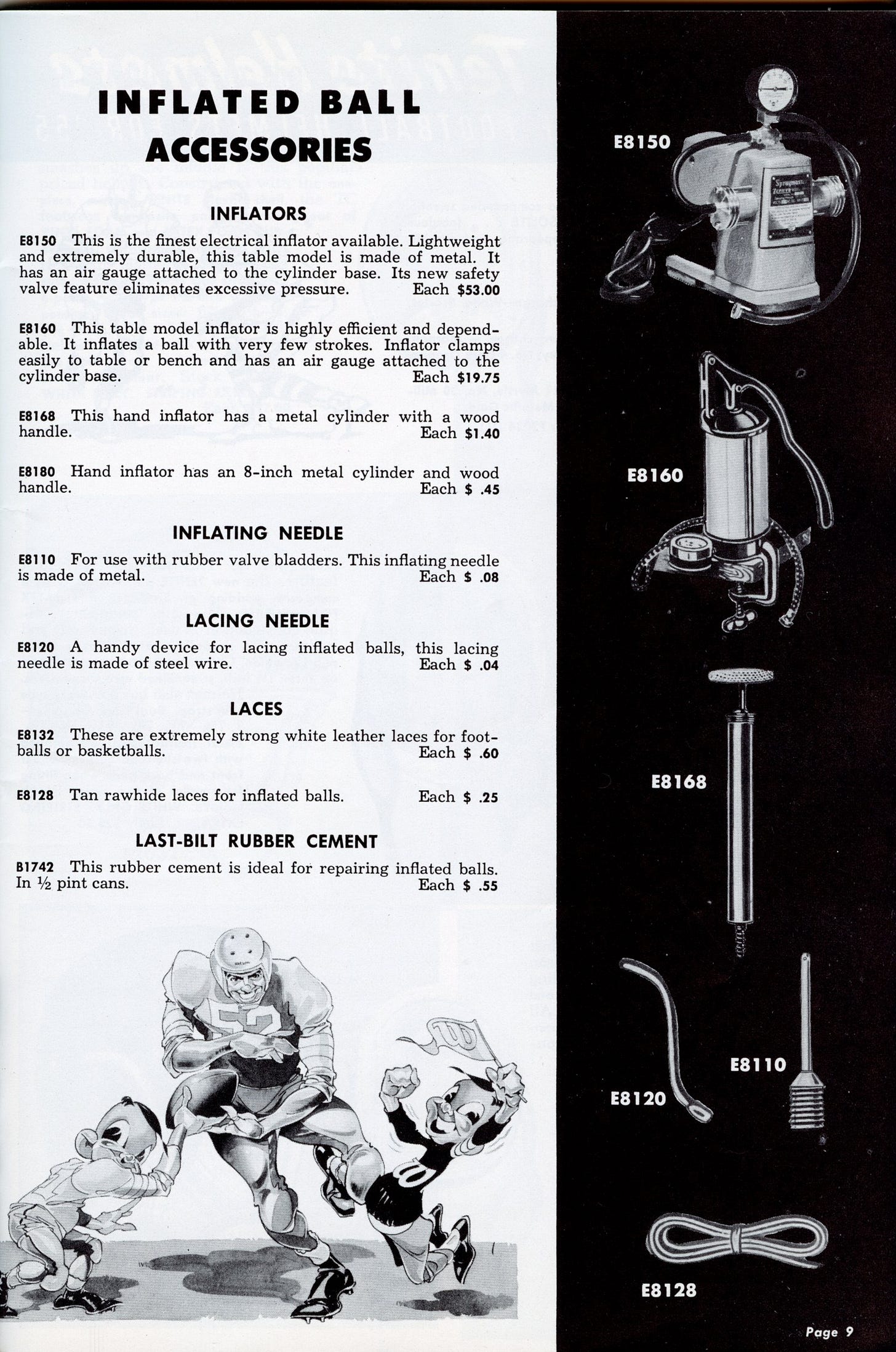

You may have noticed in the Spalding catalog illustration that the football valves of the 1920s did not use the thin and hollow metal needles we know and love today. The valves took several forms, but most were threaded, requiring the inflator to screw the pump’s nozzle onto the football’s valve. After inflating the ball, users often screwed small metal caps onto the valves to keep out dirt and water.

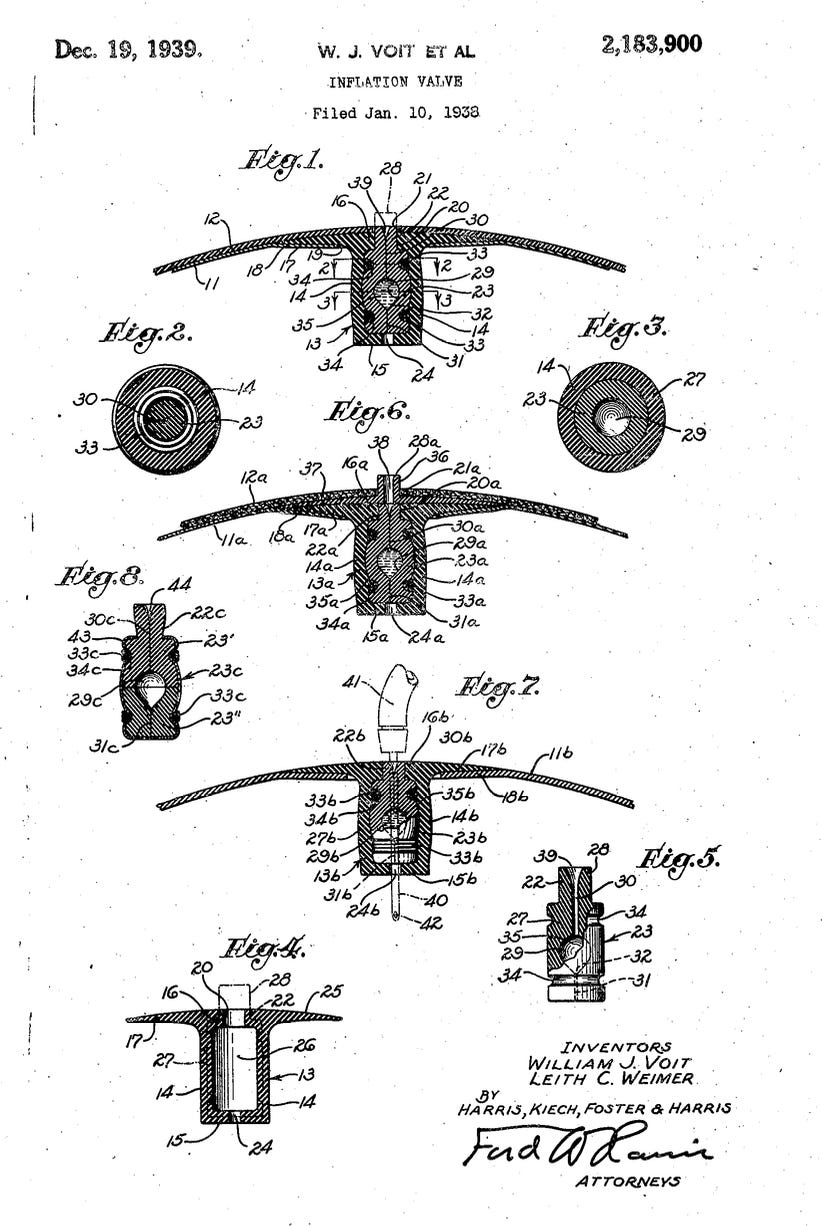

The thin, hollow needle entered the inflated ball world through William J. Voit, who received a 1939 patent for a valve with an inflating needle.

However, mainstream sporting goods manufacturers do not appear to have used inflating needles on leather balls for another decade or more, with the first reference I found coming in a 1952 Reach of Canada catalog, while Wilson showed our favorite needle in their 1955-56 catalog.

As we begin a new year, remember that progress sometimes takes time and requires more steps than we would prefer. Here’s to all of us making progress in 2026, even if it takes longer than we would like.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Subscribe now or, to learn more, buy A History of the Football.