Interclass Hazing and Class Football in the Game's Evolution

Before football became a sport played between American colleges, many schools played football-like games as interclass or hazing rituals. Largely forgotten today, interclass games helped prepare the environment for intercollegiate football before morphing into interclass football and intramurals.

Going back to ancient times, groups of men have competed in games involving kicking, batting, or throwing objects into one another's goals. The English version of these games involved young men from neighboring villages competing to kick an inflated pig's bladder from one town into another. The annual pig slaughter, which supplied the bladders, came after harvest, so they played the games as the weather turned chilly. That timing matched the start of the academic calendar in North America and encouraged playing those games in the fall.

Versions of the English games, collectively called football, transferred to the U.S., where schools and towns played one another. Harvard and Yale played rough football-like games with mass scrums in the early 1800s, three-quarters of a century before the gridiron became a twinkle in Walter Camp's eye. Both schools developed traditions of interclass games, particularly freshmen and sophomores competing with one another, which also served as hazing rituals.

Some interclass games that resembled what became football did not even use a ball. Penn, for example, had several freshmen-sophomore contests each year, one of which was the Bowl Fight, which started during the Civil War and continued until 1916. The game's action resembled early football in many respects, but the game's odd rules suggest it originated after the college boys smoked a few too many bowls.

Penn's Bowl Fight used a shallow clay bowl about two feet wide, typically inscribed with the sophomore class's graduation year, rather than a ball.

Played in an open area or football field, its rules differed for the first half versus the second. In the first half, the freshmen designated a "bowl man" by positioning him ten yards in front of the rest of the class. After the referee blew a whistle to start the game, the freshmen class surrounded the bowl man and then tried to move as a group downfield, protecting the bowl man while trying to push him under the opposite goal posts to achieve a win. The sophomores pushed in the opposite direction while attempting to seize the bowl man and place his posterior in the clay bowl, registering the win for the sophs.

The second half's rules were more straightforward. The sophomores held and surrounded the bowl while the freshmen tried to seize and break it. Like the first half, the second-half action occurred while the junior and senior classes surrounded the underclassmen, encouraging them to fight to the finish, which they often did.

The video of the 1916 Bowl Fight shows a key tactic involved pulling protectors from the scrum and wrestling them to the ground while other class members tried to penetrate the protective ring. The 1916 game was the last because the game ended with one freshman trampled to death and five others hospitalized. (The action starts at 27 seconds.)

While it may seem odd to think of pre-football hazing rituals as forerunners of gridiron football, they shared core elements:

Teams based on existing groups

Physical play that included scrums and tackling

The objective of moving a ball or other object from one group's territory into the other's

Those similarities prepared college campuses for the later adoption of soccer and rugby, formalized versions of these games borrowed from the English.

We also borrowed the concept of intercollegiate sports and a key term from the Brits through crew and regattas. When our British cousins referred to the boats representing each university, they dropped the first two syllables from "university," producing 'varsity, and eventually, varsity. We have used that term for our top school sports teams ever since.

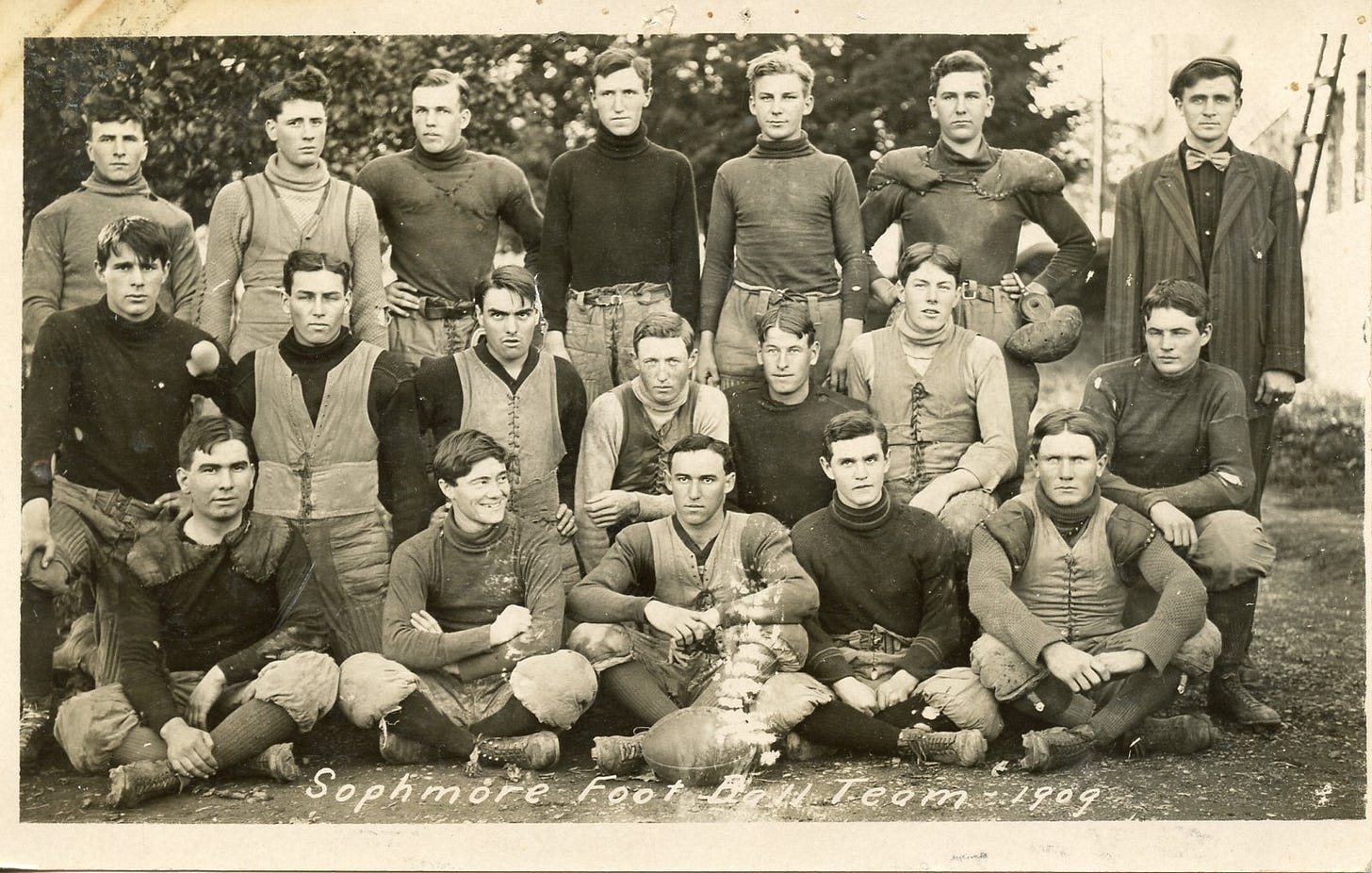

Once gridiron football took hold on campuses, the varsity did not remain the only organized football team. Many schools also developed interclass football and these teams replaced most interclass hazing contests. As played from the 1890s until WWI, class football was a full-contact game among class members who were not on the varsity or freshman football teams. Medical, dental, law, and other degree programs also fielded teams at some schools.

Class teams typically played round-robin schedules to determine the school champion, with some class teams playing outside competition. Their games received local newspaper coverage, a page or two in college yearbooks, and team members proudly mentioned their participation in their yearbook bios as seniors.

Interclass tackle football went away after WWI, in part, due to the creation of touch football in 1910. In addition, the poor physical condition of those entering the military during WWI pressured colleges to improve the fitness of all students, not just varsity athletes. The combination led to intramural programs becoming popular nationwide. Touch football allowed for more teams and greater participation across the student body, so it replaced the tackle variety.

The various campus games before football became formalized helped prepare the ground for gridiron football to flourish once it arrived and deserve partial credit for football's development. Gridiron football developed directly from rugby, but both games descend from the same mishmash of folk games that preceded them and existed alongside them for a few decades.

Click here for options to support this site beyond a free subscription.