Lon Keller and the Art of Football

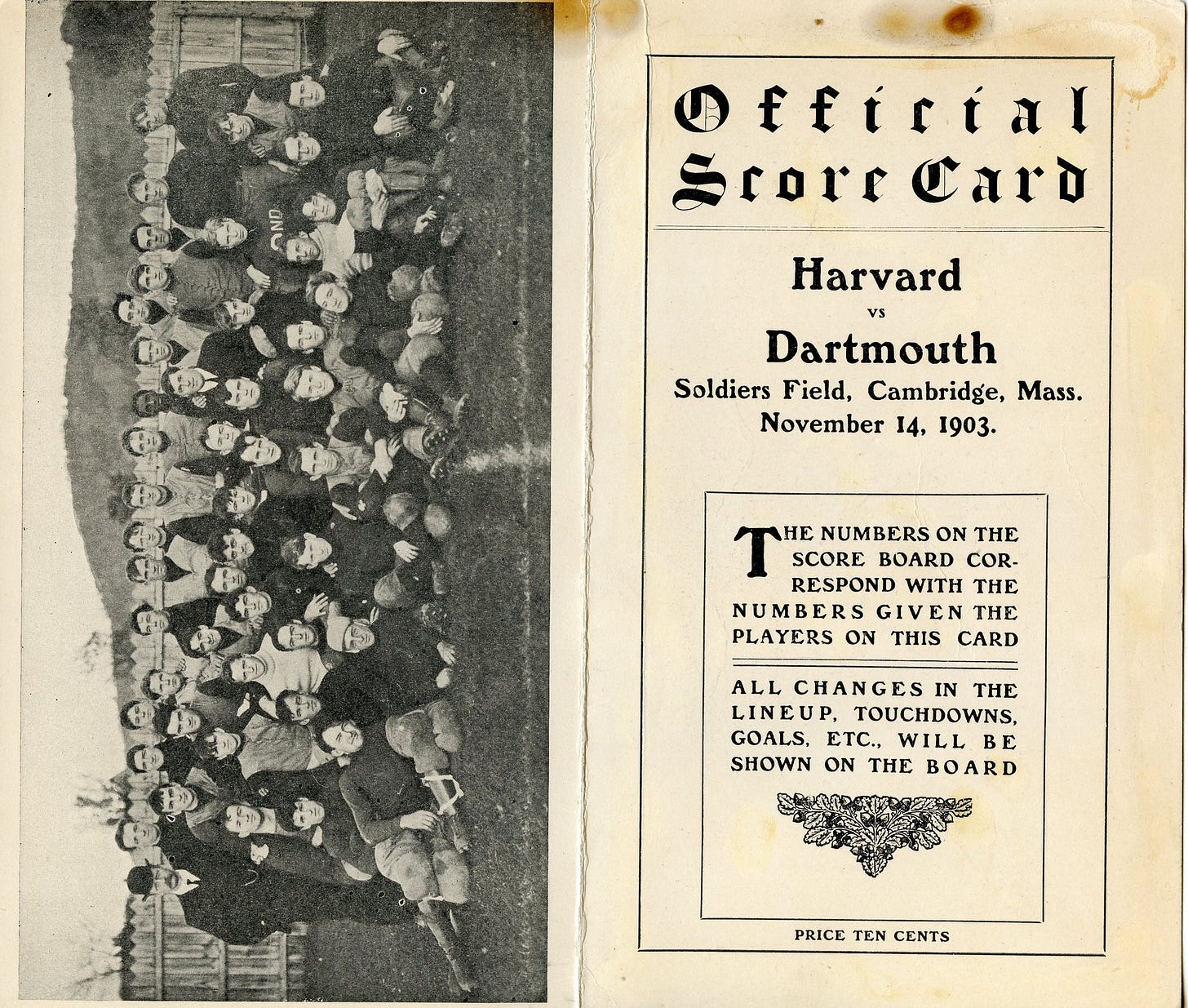

With many football games being played in empty stadiums this year, the game programs hawked at stadiums are also absent. Early football games did not need game programs. Crowds were small, and many fans knew the individual players, but as stadiums grew larger and football shifted from the open rugby style to the mass game of the 1890s, fans and the press had problems distinguishing one player from another. That led game organizers to print and sell scorecards so fans could track the players who scored and the points they earned. Unlike today's game, in which players wear numbers on the front and back of their jerseys, players did not yet wear numbers. Instead, the scorecard had a number next to each player's name, which was posted on the scoreboard when that player scored.

Scorecards grew into game programs in the 1910s as printing photographs became less expensive, but they remained simple with a dozen or so pages. Only larger schools with financially successful football programs could afford programs with custom-designed covers printed in color. Printing the colored covers was a specialty, with many produced by the Berkeley firm Lederer, Street & Zeus (LS&Z). LS&Z had salesmen across the country, and that is how Lon Keller, the star of this article, entered the picture.

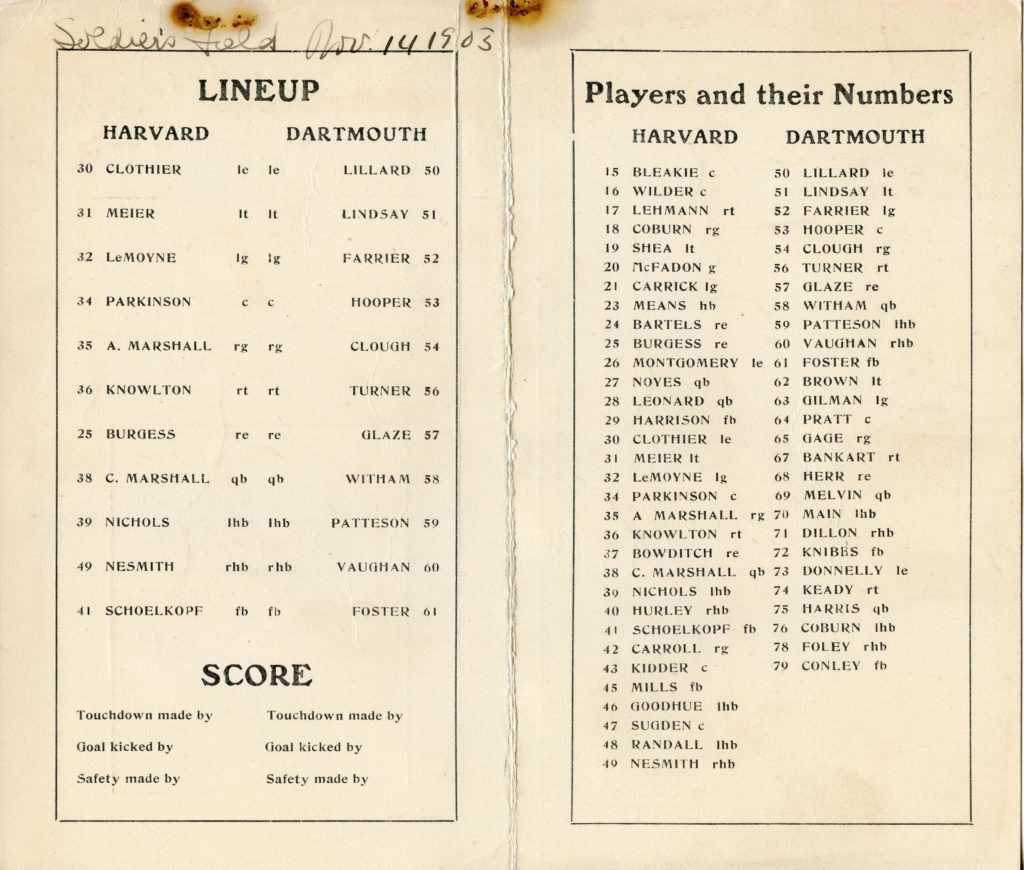

Few people who attended college and high school football games from the 1930s through the 1960s did so without seeing Lon Keller's artwork. His work graced the covers of countless game programs, which led to his being called the "Norman Rockwell of College Football." Like Rockwell, Keller worked during an age in which color photography and printing color photographs on magazine and program covers was impractical or prohibitively expensive. Illustrations ruled the day, and Keller's artwork reigned supreme, resonating with spectators and the public generally. Keller also benefited from an association with an individual and firm that revolutionized the game program business.

Keller earned his art degree from Syracuse in 1929 and came to program illustration by chance. After graduating, he found work running the University of Pennsylvania's School of Architecture store while doing freelance work illustrating newspapers and magazine covers for commercial concerns. It was Keller's good fortune that Penn's football program editor spotted Keller's commercial work and hired him to design the cover for the 1932 Penn-Cornell Thanksgiving Day game.

Keller's additional good fortune came when a salesman for LS&Z saw the Penn-Cornell program and recommended Keller to his employer, leading to Keller illustrating covers for LS&Z in 1933. Several years later, an LS&Z employee, Don Spencer, left the company with an idea for a different business model. Rather than print custom covers for a limited number of schools, Spencer's idea was to have top artists produce high-quality designs with open spaces so game-specific information could be placed on the cover via a second printing. Doing so increased the cover quality while dramatically reducing costs, making Spencer's covers attractive to large and small colleges, with local vendors adding game-specific information and marrying the covers with the local contents.

Spencer's model was tremendously successful, earning a reported ninety-five percent of the college football and basketball program markets. Top artists like Lon Keller gained nationwide attention, which increased in 1940 when Coca-Cola signed a deal to sponsor Spencer covers for high school football games across the country.

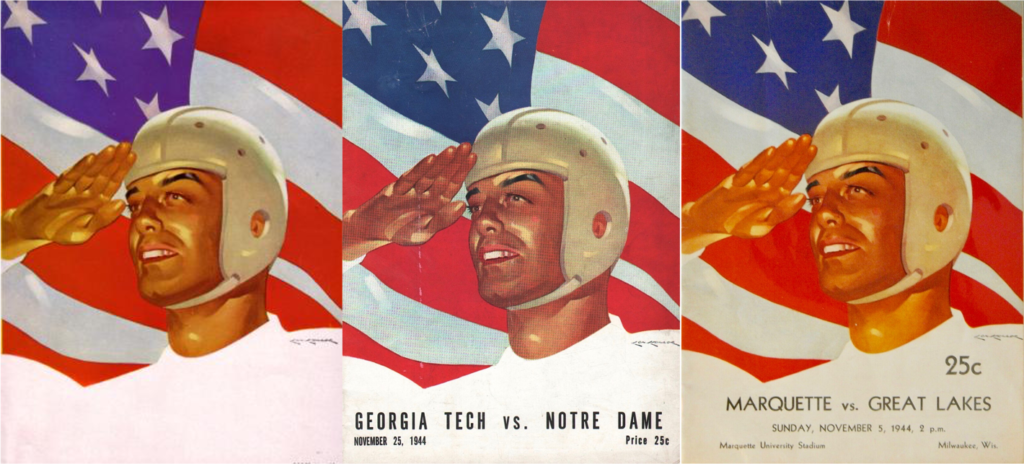

Patriotic themes dominated Keller's artwork during WWII, but the art generally presented a world in which the women were beautiful, and most were blonde. Likewise, football was played only by those who carried, threw, caught, or kicked the ball. Linemen did not warrant the artist's effort; neither did African Americans, who appeared on covers only in the latter half of the 1960s. (A New Yorker, Keller illustrated covers for the Harlem Globetrotters beginning in 1951, so he appears to have painted for his audience.)

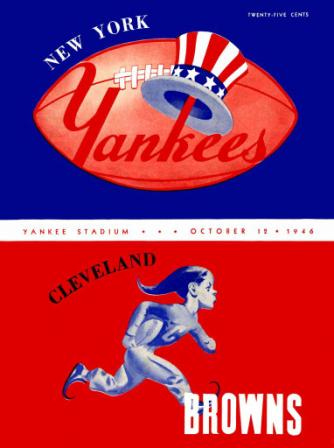

Besides basketball, Keller's work covered boxing, horse racing, the Olympics, and baseball. His work graced fourteen World Series programs, and his baseball design work remains with us today. Larry McPhail, the Yankees owner then, had Keller design a team logo for the Yankees' 1946 spring training programs. After going through several iterations that year, the logo settled on the version the Bronx Bombers use today. An adaptation of the baseball Yankees logo saw use by the New York football Yankees, an All-American Football Conference team owned by McPhail, from 1946 to 1948 before the league went belly up with three franchises joining the rival NFL.

Fifteen years later, Keller created a logo for the New York Mets, which also remains in use today.

Keller shifted gears in the 1960s and increasingly left the illustration work to younger artists while watching the demand for illustrated covers fall due to changing styles and advances in color photography and printing. Still, having designed at least 1,000 program covers over four decades, Keller played a critical role in defining the sporting arts genre while also shaping perceptions of football and other sports.

Lon Keller passed away in 1995, leaving behind a bounty of images and several iconic logos.

Most of the images shown here are used with the permission of Lon Keller's son, Jay. To see hundreds of examples of Lon Keller's work, visit his website at http://lonkeller.com.

Click here for options on how to support this site beyond a free subscription.