Maul-ins, Mauls, and the Fundamentals of Football

In recent decades, football has seen a rebirth of "mauls," that is, plays in which a ball carrier is temporarily stopped only to have his teammates push from behind to move the pile one, two, or eight yards downfield. These moving clusters were a crucial part of early football before being banned in the early 1900s, then reappearing when the rules changed once more a decade or more ago. Since most football fans are not familiar with the history of mauls -or even their name- let's review their history and role in defining two core football concepts: touchdowns and forward progress.

I've written elsewhere that we minimize rugby's influence when we say football evolved from rugby. Early football was rugby. Football's first rule book (in 1876) was copied virtually word-for-word from the rugby rule book, so both rule books and games included mauls. Since then, rugby stayed largely true to its original rules while football repeatedly changed and now is quite different from its original form. Still, numerous elements of rugby remain, including the second-generation maul. Compare them yourself by looking at the video of a rugby maul at the bottom of this World Rugby page versus videos one, two, and three of NFL teams pushing piles to advance the ball.

Football eliminated one type of maul in 1885 and the rest in 1910. To understand why, we must return to football's beginning to distinguish between tackled and downed runners. Back then, tackling referred to the process of grabbing the ball carrier and attempting to bring him to the ground, not to the outcome. Being tackled and taken to the ground was not enough for the runner to be downed. The runner could still get up and run, crawl, or slither forward to advance the ball. Only when the runner was held on the ground and yelled, "Down," did the play end.

As in rugby today, early runners in football often stayed on their feet while being tackled, so their teammates bound to them, pushing and pulling toward the goal line while the defense did the same in the opposite direction. Critically, with all the back and forth, the offense could lose ground during a maul because football had not yet embraced the concept of forward progress, which had significant meaning for a form of maul called a "maul-in" that occurred beyond the goal line.

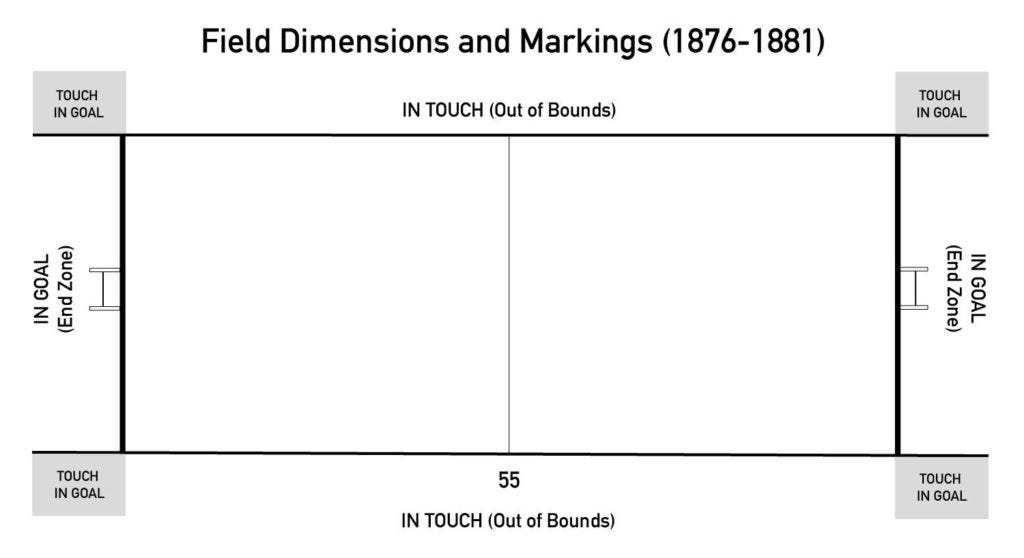

Maul-ins get their name from the early terminology used to describe football fields. The illustration below shows the football field markings used through the 1881 season. The area we now call "out of bounds" was "in touch" and those past the goal lines were "in goal." The "in goal" areas lacked end lines until 1912 when they became "end zones." (For more on that, click on my article, Football Before End Zones.)

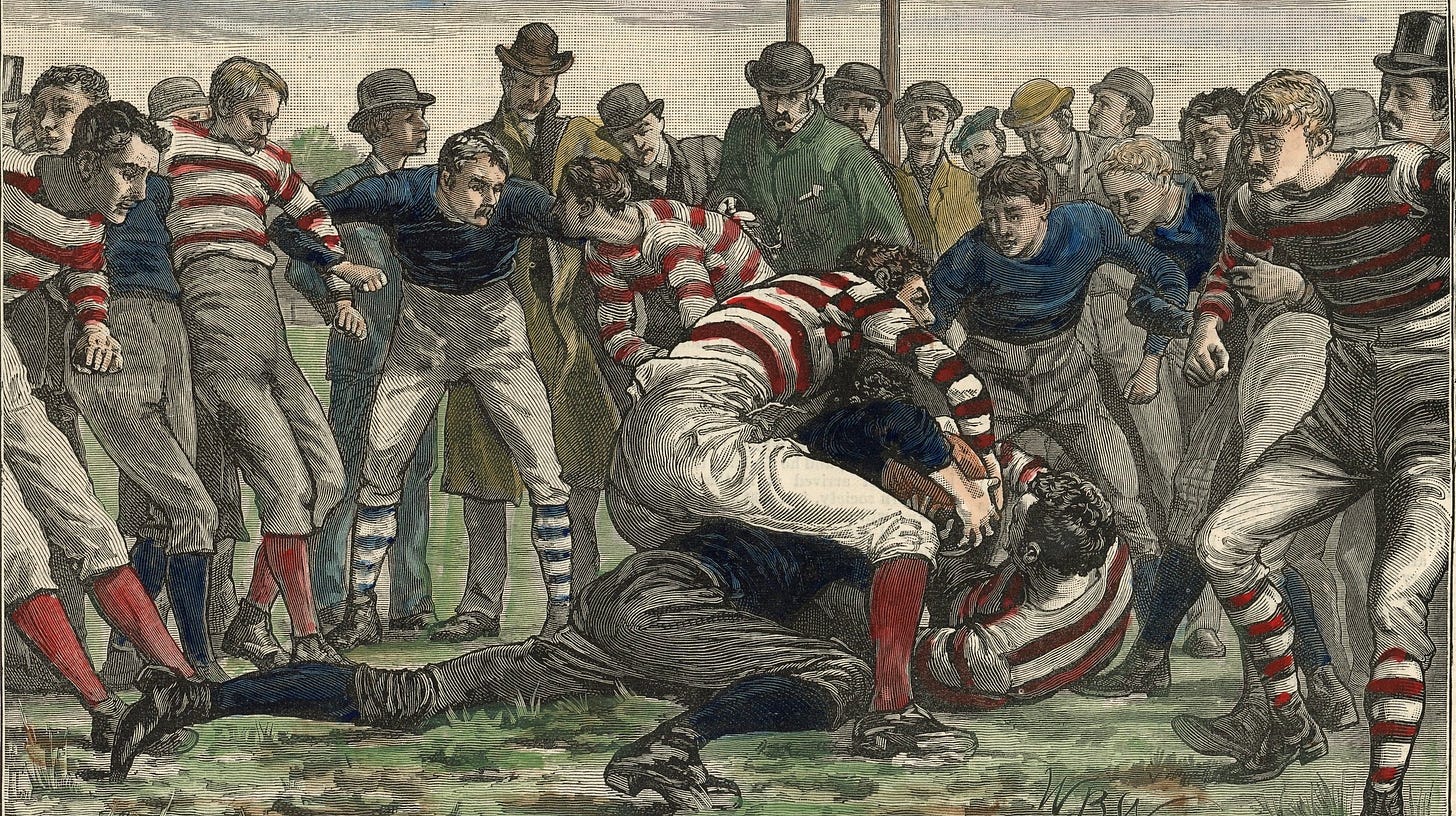

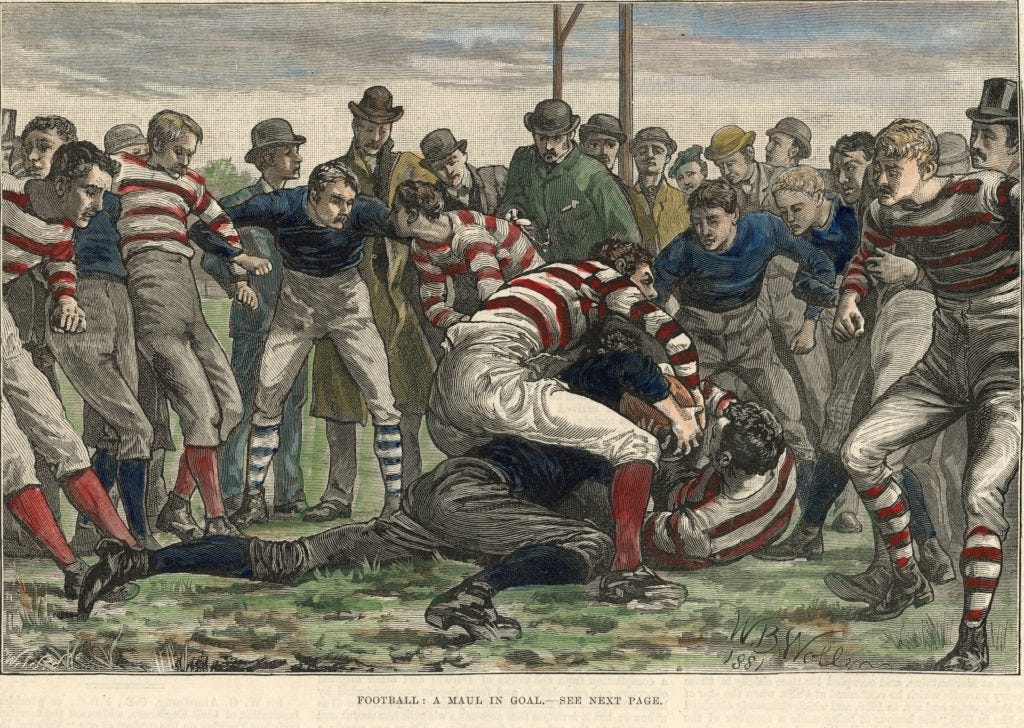

Mauls sometimes started near a goal line and then crossed it, resulting in a "maul in goal" or "maul-in." Maul-ins had three potential outcomes. The maul-in could be pushed back into the field of play, a defender could take the ball from the ball carrier, or the ball carrier could touch the ball to the ground in goal to achieve a "touch-down." The touchdown occurred only when the ball carrier touched the ball down in goal.

There were important rule differences between mauls on the field of play and maul-ins. Any player could participate in a general maul, but a maul-in was restricted to those already involved when the ball crossed the goal line. In addition, those who lost touch with the maul in goal could not reengage.

Unfortunately, only a handful of newspaper reports mention maul-ins during games of the period, and their mentions are brief. Likely the best-documented maul-in occurred during Amos Alonzo Stagg's first practice as a Yale freshman when he lined up with the scrubs (aka scout team). Thankfully, he wrote about the event forty-five years later.

Lining up with the scrubs, we encountered almost immediately a farcical left-over from the Rugby Union rules, called the maul-in goal. Alex Coxe, 290 pounds and big boned, was at left guard for the varsity. Not content with using his bulk in the line, …. Captain Richards was employing Alex to lug the ball. Tackling Alex waist-high or higher, as the rules enforced, was a quixotic enterprise, and he dragged us steadily toward our goal line.

Another steam-roller sortie and he went over the line, with Tillinghast of the scrubs hanging on. Coxe landed on his back, and the ball was not down in that day until it actually touched the ground. If Tillinghast could keep Coxe from turning over, or could wrest the ball from him, there would be no touchdown. This was the maul-in goal, legislated out the following year, and the rules stipulated further that it was strictly a private fight between the man with the ball and the man or men who had their hands on him when he crossed the goal. No one else could join in.

What Tillinghast lacked in weight he made up in fight. While twenty of us looked on, the two fought it out for fifteen minutes -and I do not exaggerate. It ended in a victory for the scrubs, Tillinghast getting the ball away from the winded Coxe.

Amos Alonzo Stagg, Touchdown, 1929

Although Stagg's description of the maul-in is amusing, fans had little interest in paying to watch fifteen-minute maul-ins and, more important, participating players risked injury. That put maul-ins on the chopping block, and the Intercollegiate Football Association resolved the problem in 1885 by eliminating the need to touch the ball down in goal. Instead, the new rule awarded the touchdown as soon as the ball touched the goal line in an offensive player's possession. Removing the need to touch the ball down was the first step in introducing the concept of forward progress to football.

Of course, the 1885 rule eliminating maul-ins did not end mauls in general since the ball carrier still had to be brought to the ground when mauls occurred between the goal lines. Moreover, as football moved away from the open rugby style of the 1880s to the mass and momentum style of the 1890s, mauls or maul-like blocking became common in wedge and momentum schemes.

Rugby also restricted mauls more than football. Whereas rugby only allowed players to push the runner, football allowed pushing, pulling, lifting, and carrying the runner, and combinations of those were thought to exemplify good teamwork. Stagg and Williams' book of 1893 includes numerous play designs instructing players how to execute mauls, and those techniques stayed in use as the century turned. For example, a reporter praised George Woodruff's 1901 Penn team after its win over Penn State:

Woodruff has often said a great deal of the effectiveness of his system is especially dependent on aiding [the runner]. This year's men seem to have caught his idea early in the season, for yesterday they pushed and tugged and twisted and whirled, carrying the runner on for long gains, time after time.

Philadelphia Inquirer, October 6, 1901

However, since mauls were not beneficial to football players' bodies, they were again targeted for reform and a 1906 safety-oriented rule applied the concept of forward progress to the entire field. Runners were considered down when any part of their body besides the hands and feet touched the ground or when their forward progress stopped. Teammates could still aid the runner until 1910, but forward progress applied to those mauls. New rules in 1910 finally prohibited pulling, lifting, carrying, pushing, or charging into the ball carrier to assist his forward progress. This rule effectively made mauls and similar assistance to ball carriers illegal in American football.

Those prohibitions remained in effect for ninety-five years. The NFL legalized pushing or charging into a teammate carrying the ball in 2005, and the NCAA followed suit in 2013. (Pushing remains illegal in high school football.) It is now common to see teammates push the ball carrier in short-yardage or goal-line situations. Some pushing is planned, such as running backs pushing quarterbacks as part of a sneak, but most instances are unplanned as teammates simply take the opportunity to move a teammate forward.

It will be interesting to monitor the use of mauls in the future. Some teams will likely add planned mauls to their playbooks, just like the Wildcat formation found a place in playbooks. Mauls are fun examples of big boy football in limited doses, but they were removed from football more than a century ago because they are dangerous. Should a top running back or quarterback suffer an injury during a future maul, the perception of mauls may change among rule-makers.

A big thanks to Yazid (@UmayyahYazid on Twitter) for suggesting this topic and providing links to recent NFL mauls.

Click here for options on how to support this site beyond a free subscription.