NFLers Fly High with the 1956 Eglin Air Force Base Eagles

As has been the case for much of the nation's history, America's military forces are staffed by volunteers today. The military drafts of the past were primarily used primarily in wartime -such as WWI and WWII- even reaching the point that the armed forces banned enlistments from December 1942 to the war's end so they could better manage the flow of men into the services.

The draft authorization expired in 1947 before being reinstated in 1948 due to insufficient numbers of volunteers and remained in force until 1973. On average, two million men were drafted each year from 1941 to 1945. Those volumes dropped quickly following the war, increasing to four hundred to five-hundred thousand during the Korean War, before falling again to 150,000 or lower in the second half of the 1950s.

Some civilians -particularly college students - received deferments, which ended upon graduation or other status changes, after which the former students were eligible for one- or two-year stints working for Uncle Sam. Elvis Pressley was undoubtedly the most famous draftee of the Fifties. He reported for duty in March 1958 and, by all accounts, served faithfully, like most draftees. Among other celebrities receiving draft notices were former college football players, some with NFL experience. Pro clubs selected and signed players only to see some drafted by a military that did not engage in bidding wars for the players' services.

As in WWI and WWII, military bases of the 1950s fielded football teams for morale and public relations purposes. Like the colleges, their football teams had little connection to the primary purpose of the broader organization. But, unlike the colleges, the military did not recruit or draft for athletic ability, and the talent mix on their teams reflected that approach. Most had a mix of high school, college, and professional athletes, the former being more common than the latter. Still, there was significant talent spread across the military teams. For example, only three of the forty-six men named to the 1956 All-Service teams (separate teams for the Army, Air Force, and Navy/Marine Corps) had not played college football.

Like JUCOs, talent levels varied from year to year. Most drafted players only served for one or two-year stints, and players transferred from one base to another due to training or duty requirements. The fluid talent pools made guesswork of preseason predictions, but prognosticators knew some teams had more talent than others.

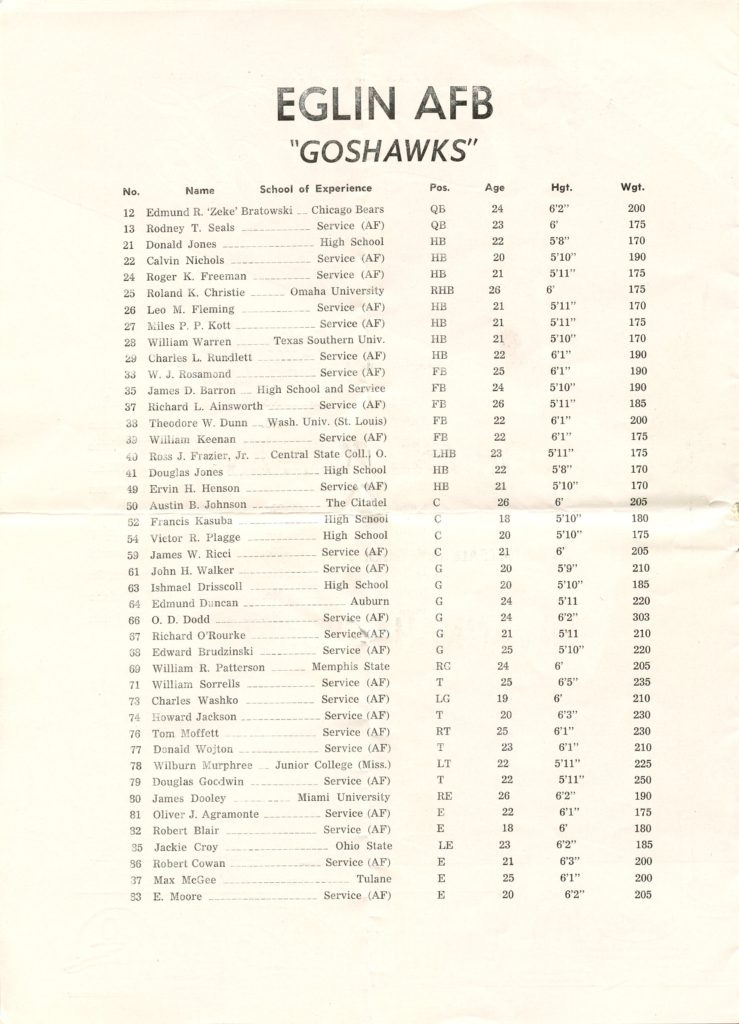

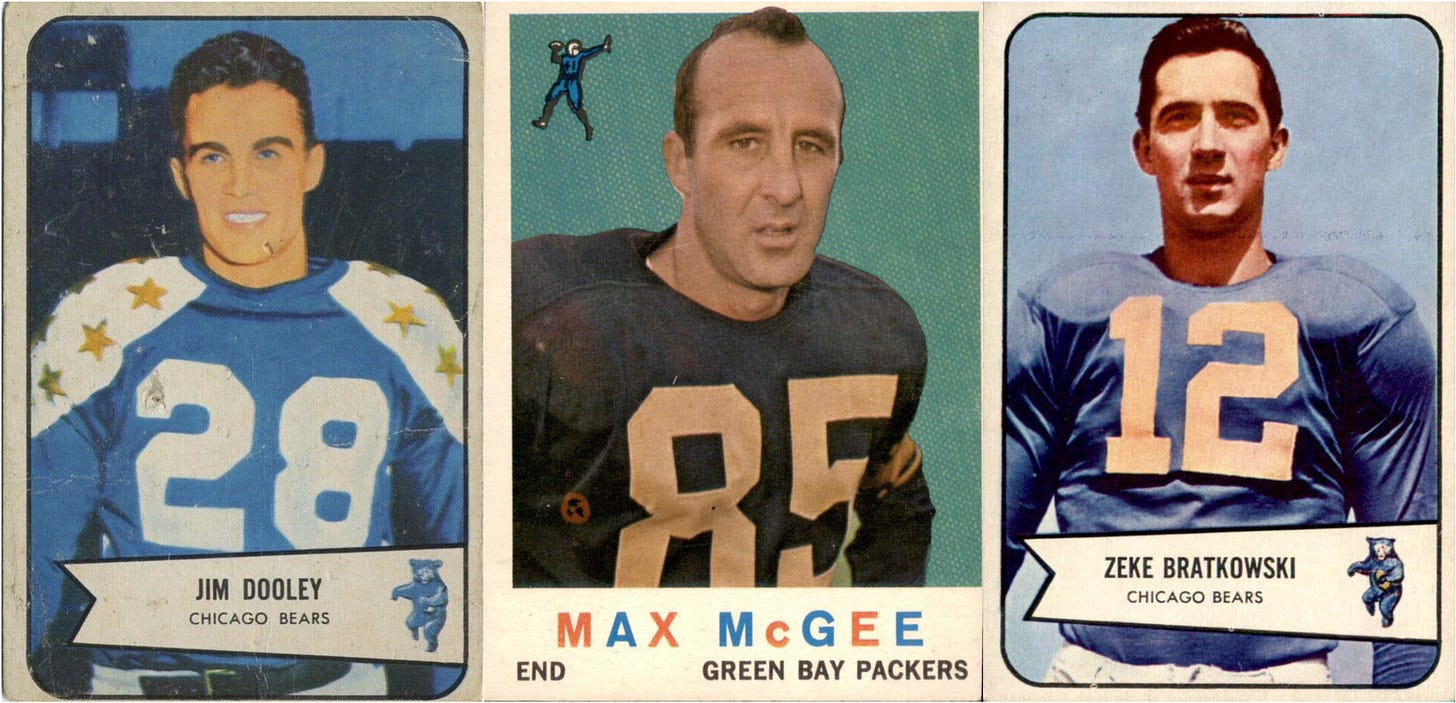

One team predicted to have a successful season was the 1956 Eglin Air Force Base Eagles, with three of its players making the All-Air Force team at the season's end. The stars included Jim Dooley, an All-American end at Miami, drafted after spending three years with the Chicago Bears. Max McGee, who switched between halfback and end for Eglin, played his rookie season with Green Bay before the Air Force made him pack his duffel bag. Their Eglin AFB and All-Service teammate, Edmund Bratkowski, better known as "Zeke" or "The Brat," became the NCAA All-Time passing leader as a senior at Georgia in 1953. Based on that combination of talent, the Eglin coach rightly decided to throw the ball with frequency.

Elgin AFB, which sits in Florida's panhandle, mostly played other military teams from the Southeast. Unfortunately, their games did not gain the media attention of the prominent colleges. Still, in the days with only one or two college games televised per weekend, the Eglin-Pensacola game was televised, area newspapers covered their season consistently, and up to ten thousand fans attended their games. Likely the most famous reporter covering the Eagles was Airman First Class Hunter S. Thompson, sports editor of the base newspaper, The Command Courier. Hell's Angels and his 1971 Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas are his best-known works.

As expected, Eglin won most games due to a touchdown toss or three from Bratkowski to Dooley or McGee. They flung the ball around pretty well for amateurs, but the uneven quality of the Eglin roster gave their opponents opportunities to score points as well. Entering the last game of the season at 6-2, the Eglin Eagles team faced the capital area's Bolling Field for the right to play in the Shrimp Bowl, the military's national championship game. Unfortunately for Eglin, Dooley did not play for Eglin that day as Bolling and its several former college running backs slipped by Eglin, and later bested Fort Hood in the Shrimp Bowl to claim the national service title.

Jim Dooley, it turns out, missed the Bolling game because his military time had run out. He quickly left Florida and returned to the friendly confines of Wrigley Field and the Bears, playing in their last several regular-season games and helping Chicago to the 1956 NFL title game. Dooley's final season playing in the NFL came in 1961, after which he became a Bears assistant for five years before becoming head coach for four more.

Bratkowski returned to the Bears for the 1957 season, spending four years in Chicago, and two and one-third seasons with the Los Angeles Rams before the Packers acquired him off waivers during the 1963 season. Bratkowski became Bart Starr's super-sub, helping the Packers to three consecutive NFL championships, including wins in the first two Super Bowls. After retiring as a player, Bratkowski spent the next twenty-five years as an NFL assistant, primarily handling offensive coordinator and QB coach duties.

Max McGee returned to Green Bay for the 1957 season, two years before Vince Lombardi became head coach, staying for all but Lombardi's final season with the Pack, winning five NFL championships and two Super Bowls in that time. A backup toward the end of his career, McGee expected to see little action in Super Bowl I and spent the night before breaking curfew and the seals of a few liquor bottles. However, forced to enter the game early due to a teammate's injury, McGee famously made a one-handed catch to score the first touchdown in Super Bowl history. McGee was a successful restauranteur and color analyst following his NFL playing career.

While the service academies continue their football traditions today, football teams comprised of active-duty personnel largely disappeared in the 1960s. Instead, intramural competition became the option for those seeking playing time. At the same time, the increased availability of televised college and pro football took over the entertainment function among the nation's service personnel. Still, military football allowed some to extend their playing careers beyond high school, while others used it to stay sharp while taking an enforced year or two away from their professional careers.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.

It is great to hear from you since you played for Eglin and proudly wore #9. I'd be happy to add to this story and write another article if you have memories or images you would like to share. Military or service football is a fascinating part of the game's history.

Jim Ricci Center 1956-57

The game at Bolling was played on a cold wet weather day.

The difference in that game was the officials.

Roland Christie broke loose for a 65 yard touch down, once he crossed the goal line the official dropped a flag and called us for being offside.

Some of the fans at the game informed us that Bolling never loses at home