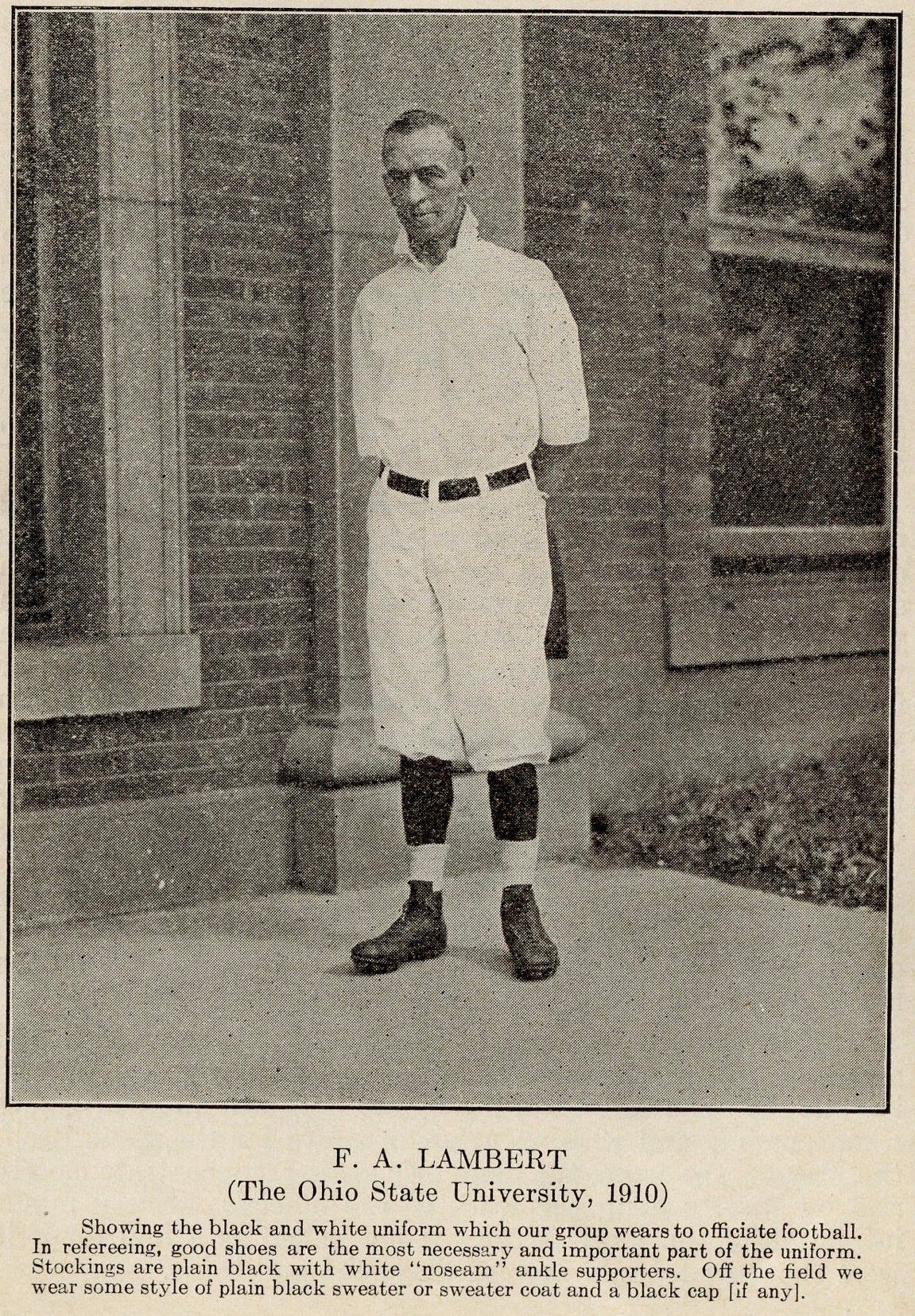

Officiating and Fonsa A. "F. A." Lambert

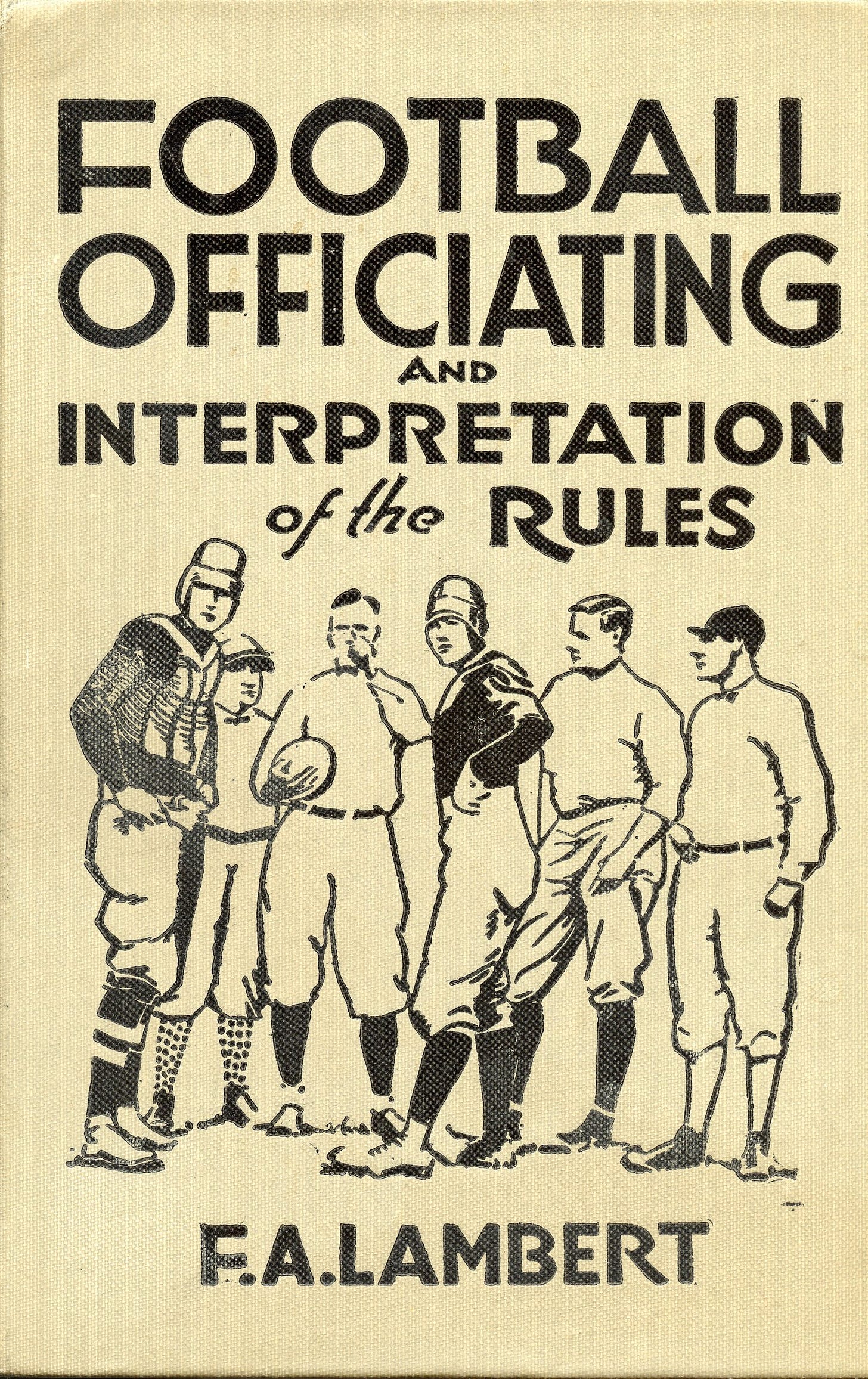

Fonsa A. "F. A." Lambert has been mentioned in previous Tidbits discussing variations in the referees' first down signal and officials' uniforms, but this Tidbit will cover him in more detail. Lambert was a top official in his day who published How to Officiate Football in 1926. As the first, or among the first, books detailing the philosophy and mechanics of officiating, any serious official of the day read it thoroughly.

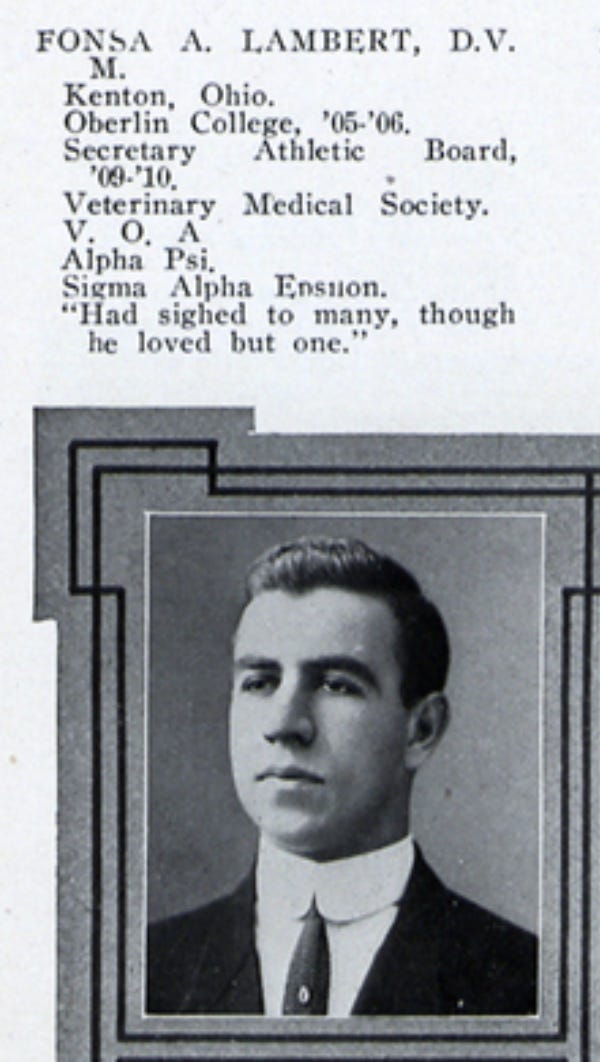

Lambert grew up in Ohio and played freshman football at Oberlin in 1905. He remained there another year before transferring to Ohio State, where he graduated with a Doctor of Veterinary Medicine, then an undergraduate degree. Though he planned to open a veterinary hospital, his plans changed when he joined Ohio State's faculty that fall.

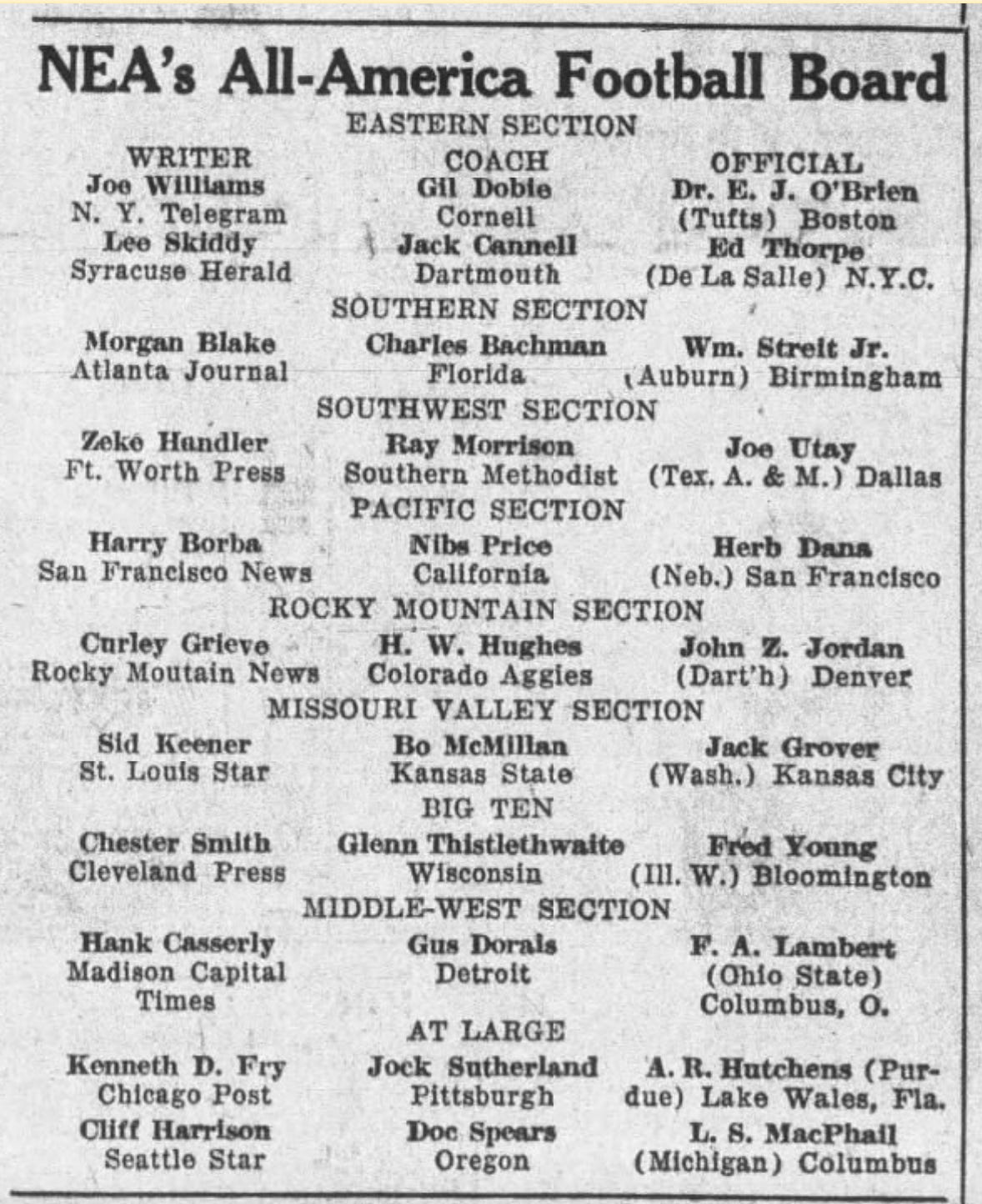

Lambert began officiating about that time, working his way up from high schools to small colleges, and was refereeing major college games in the Midwest and South by the late Teens. He also handled early NFL games. Eventually, working approximately 550 games during his career, he was on NCAA rule-making subcommittees and participated on the Newspaper Enterprise Association (NEA) board to select the All-American team.

His How to Officiate Football is a time capsule of football in the mid-1920s. Part an authoritative text and part opinion, Lambert positioned the referee as the king of the officiating crew. For example, he emphasized that only the referee could signal a touchdown by raising his arms. The other officials, who did not carry whistles, were to raise one arm in the air to signal a dead ball. Likewise, the other officials could not signal an incomplete pass by swinging their arms in a horizontal plane. They were to raise one arm to signal a dead ball and wait for the referee to indicate the incompletion.

Likewise, Lambert would not work with other officials that carried whistles, and he dismissed linesmen carrying rods or poles on the field, a practice that began before down boxes became part of the chain gang.

You need no pole or rod; the assistant linesman is using it and marking the point of each down on the sideline. Carrying a pole or rod is a handicap to the linesman and hazardous to players.

Lambert regretted that a consistent system of referee signals had not yet developed. However, he mentioned Frank Birch's system, which football adopted several years later, and a second system in which cheerleaders signaled the penalties to the home crowd.

Other Lambert strictures that no longer apply due to rule changes and other developments include:

Following the extra point attempt, the referee should immediately ask the captain of the team that has been scored upon whether he wants to kick or receive the ball.

Only one player is allowed to talk in the huddle. (Regular huddling was relatively new and controversial when he wrote the book.)

Insisting fields get marked in five-yard intervals rather than the 10-yard stripes used in some locations.

Wiping the ball was allowed only during timeouts.

His final games as a referee came in November 1932 when he refereed the Kentucky-Tennessee game in Knoxville on Thanksgiving Day and then headed to the Steel City for the Pittsburgh-Stanford game on Saturday, which happened to be Pop Warner's last game coaching Stanford.

Unfortunately, Lambert's final moments were inconsistent with the high standard he set on the gridiron. In March 1933, Lambert was drinking and became abusive with his wife. When his 17-year-old son came to his mother's aid, Lambert grabbed a gun and was himself shot in the struggle, dying soon after telling others that his son had acted in self-defense. It is a sad ending for any man, but particularly sad because of his contributions in other aspects of his life.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.

Wow...he called the final penalty on himself. I've seen movies with worse premises.