Origins of the College Football Bowl System

The current College Football Playoff system is the fourth attempt to install a rational championship mechanism atop the college bowl system that emerged in the 1930s from a mishmash of postseason games and scheduling formats. The bowl system that developed was not inevitable. Other postseason models were tried and might have taken hold, but they did not. Likewise, other warm-weather cities might have become premier bowl destinations under slightly different circumstances.

While football conferences remain regionally focused today, the game was far more regional before WWI. Intersectional play was relatively rare due to varying eligibility standards across conferences, a national transportation system that limited regular-season travel, and faculties that frowned on extended trips during or after the regular season.

Today's Ivy League teams ruled the game but played primarily among themselves after feasting on lesser schools in the early season. A few contests with Mid-Atlantic and Big Ten schools dotted their home schedules, but even fewer intersectional away games. Yale did not play a game west of the Allegheny Mountains until 1931, and Harvard's appearance in the 1920 Rose Bowl was the first outside the East. Its first regular-season game outside the region came during WWII. A similar pattern occurred on the West Coast: California did not play a regular-season game east of the Rockies until 1947.

Northern and Southern teams also saw little of each other. Vanderbilt and North Carolina were more venturesome than others, but today's SEC teams played only a handful of games against the Big Ten or anyone else from the North until well into the 1920s. Rarer still were games between West Coast and Eastern teams. Traveling from anywhere east of the Mississippi to the morning shade side of the Rockies was time-intensive and expensive. Such trips generally occurred over the holidays and only when the Eastern teams received sufficient guarantees or gate receipts from multiple games to make the trip financially viable.

The first postseason games to warm-weather locales came when Chicago, led by Yalie Amos Alonzo Stagg, rode the rails west to play Stanford and their fellow Yalie coach, Walter Camp, over Christmas break in 1894. Their Christmas Day game in San Francisco was the first athletic contest between teams east and west of the Rockies. The teams played a neutral-site game in Los Angeles on the 29th before Chicago met the Reliance Athletic Club three days later, marking the first New Year's Day game played by a college football team. Carlisle, which played anybody anywhere, headed west in 1899 and 1903, but few teams followed them over the next two decades.

Whereas Chicago and Carlisle scheduled their games unilaterally, the Tournament of Roses in Pasadena pioneered the invitation model. Seeking to draw tourists from the East and Los Angeles, they invited Stanford and Michigan to play on New Year's Day 1902. Unfortunately, scheduling difficulties the next year, and Stanford and Cal's decision to drop football after the 1905 season resulted in a long pause before the second Tournament game occurred.

The emergence of Washington State, Oregon, and Washington as football powers and football's return at Cal encouraged the Rose Committee to restart Pasadena's East-West Tournament game in 1916. (An image from the 1917 game at Tournament Park is shown atop the page.) It proved so successful Pasadena built the massive Tournament of Roses Stadium in time for the 1923 New Year's Day game. Since the Yale Bowl influenced the new stadium's design, a Pasadena reporter referred to the new stadium as the Rose Bowl, a name soon applied to both the stadium and the game.

The Rose Bowl, part of a larger festival that attracted attention and tourists to Pasadena, was a model for other cities but one that was difficult to follow successfully. Havana hosted LSU in a game with the University of Havana in 1907, the first of eight games that never really worked. San Diego's Chamber of Commerce took a stab in 1921 and 1922 with their Christmas Classic games at Balboa Stadium, but their inability to attract an Eastern team in 1923 led to its demise. Los Angeles tried to fill its new Coliseum when USC played Missouri in the 1924 Christmas Festival game, while Dallas sponsored the Dixie Classic in 1922, 1925, and 1934. None of these postseason matchups between two college teams had the staying power of the Rose Bowl.

Matching two top college teams in a postseason game was made more difficult because various conferences and independents prohibited their teams from playing in these games. That led some locations to turn to an alternate format: all-star games between recent graduates not subject to such restrictions. Cleveland, which was not a warm-weather destination at the time any more than now, held an East versus Midwest all-star game in 1924 that proved unsuccessful. San Francisco's Shrine Game had top Eastern players face those from the West beginning in 1925 and had a brighter future. Dallas' Dixie Classic, which had invited two college teams in the past, switched formats in 1928 and 1929, with Big Six and Southwest Conference all-stars facing one another. A number of other all-star games came and quickly went as well.

The final approach to matching college teams in postseason games saw teams unilaterally schedule games over the holidays. Stanford played postseason games with Pitt in 1922 and Army in 1929, besides their 1924, 1926, and 1927 Rose Bowl appearances. (The 1922 Pitt-Stanford clash occurred despite Pop Warner agreeing to leave Pitt to coach Stanford. Pitt would not release Warner from his contract, so he could not join Stanford until 1924.) Cal played three Rose Bowls in the 1920s, but a feud with the Tournament of Roses led to their scheduling two postseason games with Pitt in the 1920s and three with Georgia Tech in the 1930s. USC, Cal, Oregon, and others made holiday trips to Hawaii for games with military or local all-star teams.

The Rose Bowl and the all-star Shrine Game were the only annual postseason games to survive the end of the 1920s and early years of the Depression. Still, as the nation began recovering, business leaders in other cities touted the benefits of football games for attracting tourists. Those cities tended to be in the South rather than the West, where teams had an easier path to the Rose Bowl.

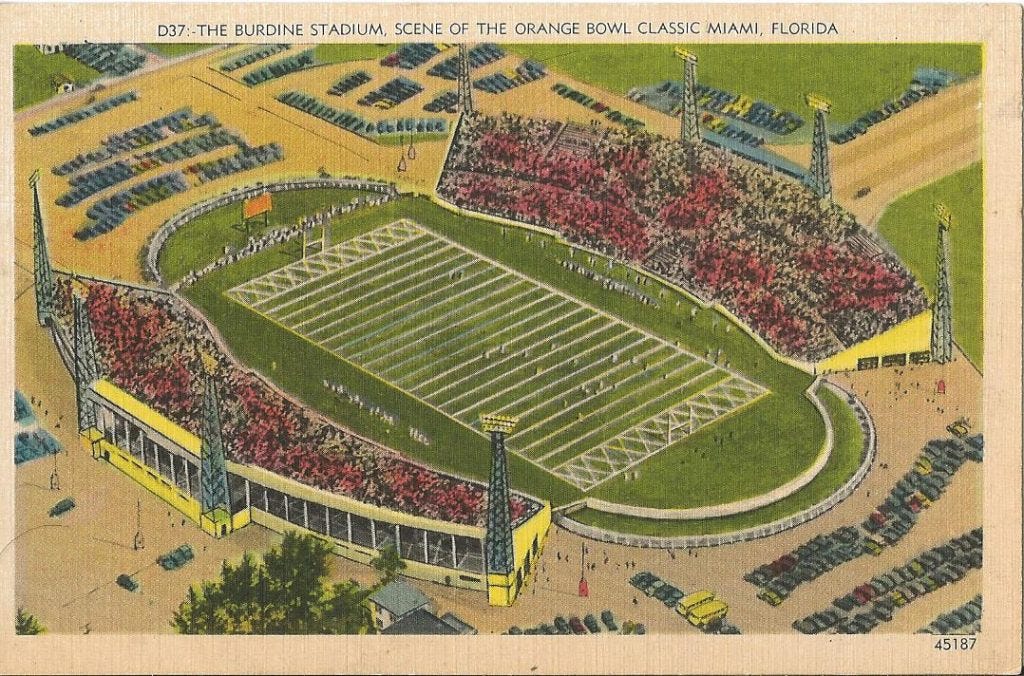

The Southern bowls that developed also granted favored status to local and Southern teams, in part due to their tight budgets. The football game tied to Miami's Palm Festival was such a rinky-dink affair that the organizers had to borrow bleachers seating 5,000 from the city -the added capacity was more than twice the game's actual attendance. Manhattan College played in the first game and was paid so little they traveled to Miami by boat rather than train to save money. Manhattan's opponent was the University of Miami. When Miami's coach fell ill, they brought in Illinois' head coach, Bob Zuppke, who led the Miamians to a 7-0 victory. Rechristened the "Orange Bowl" for the 1935 game, the game remained a financial risk until the 1939 game fortunately paired #2 Tennessee and #4 Oklahoma.

Likewise, the Sugar Bowl debuted in 1935 after a decade of the local business community discussing its potential. Tulane hosted the Pop Warner-led Temple Owls in the inaugural game. Warner had plenty of experience traveling the country from his days at Carlisle. He also brought postseason experience from his time at Pitt and Stanford, but the Philadelphians still fell to the local Tulane team. LSU played in the next three Sugar Bowls. LSU deserved the invitations, but their participation also minimized travel costs while maximizing local interest. Unfortunately for Tigers' fans, they lost once to Texas Christian and twice to Santa Clara.

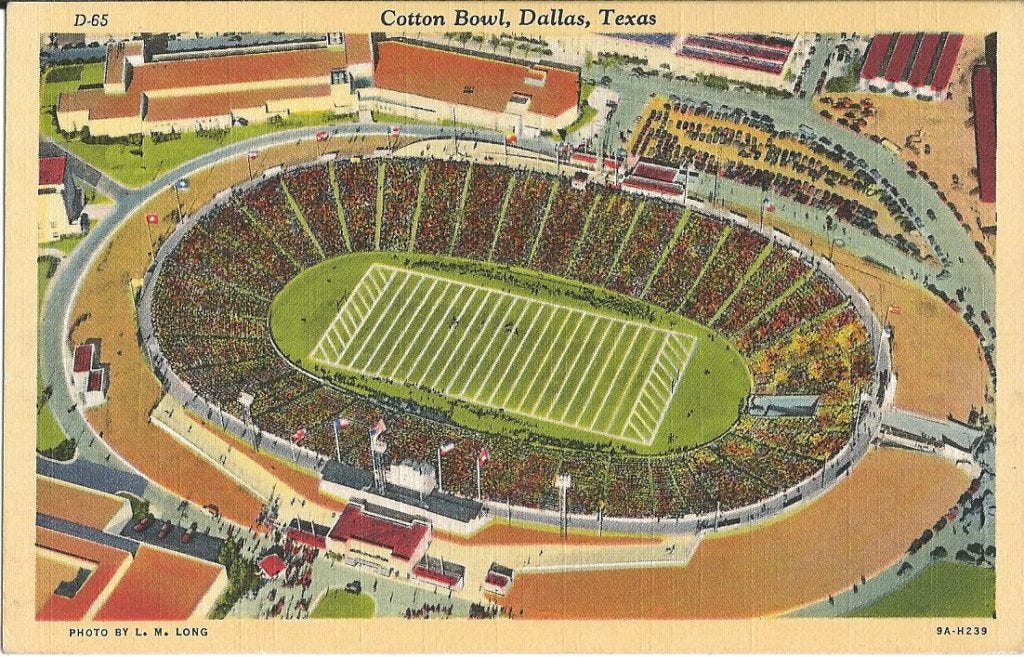

After running into difficulty with the Dixie Classic, Dallas followed the trend and renamed Fair Park Stadium the Cotton Bowl in 1936. It hosted the first of its namesake games in 1937 and lost money, but a deep-pocketed sponsor sustained the event until the 1938 game proved a moneymaker.

The Orange, Sugar, and Cotton Bowls cloaked themselves under the "bowl" naming convention popularized by the Rose Bowl, as did a host of followers over the years. "Bowl games," which initially referred to contests played at Yale, became the accepted term for postseason games and is now embedded in the very name for college football's highest competitive division: the FBS or Football Bowl Subdivision.

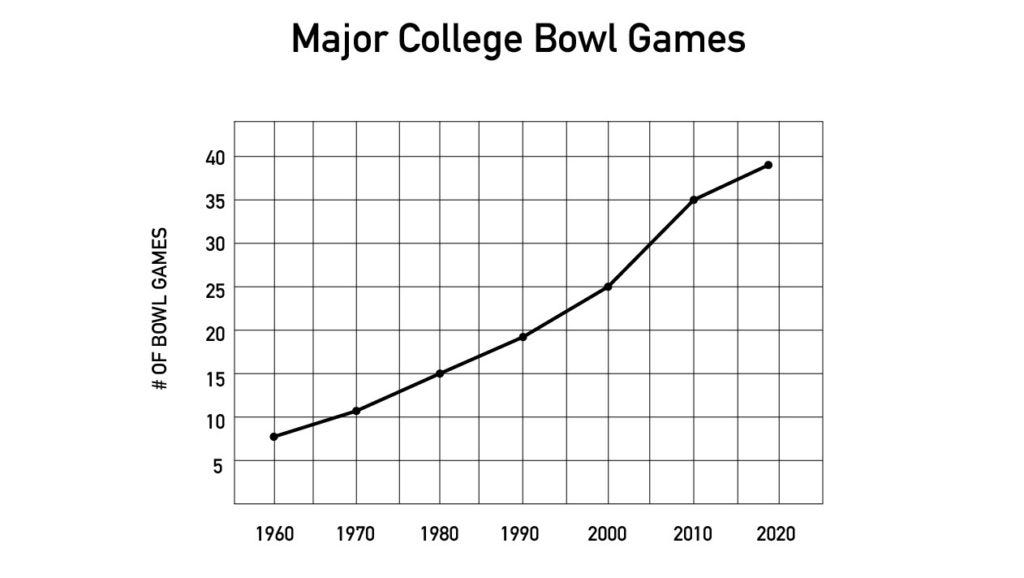

The number of bowls exploded over the last sixty years. The 1960 season ended with eight major college bowl games compared to the thirty-nine that followed the 2018 season. The number of bowls was kept low for many decades due to the schools and conferences that prohibited or limited bowl participation until the 1970s. The dramatic expansion of the bowl system that has occurred is not due to more cities sponsoring holiday festivals; rather, the influx of television money has made additional bowls commercially viable. During the 2018 bowl season, ESPN or its sibling networks televised thirty-five bowl games. ESPN owned and operated fifteen of those, and three more were owned by NFL teams. Other television networks owned and operated five additional games, making nearly sixty percent of all bowl games made-for-TV events. That situation is not inherently good or bad, but it makes clear that most bowl games now exist to provide content for television networks or to fill otherwise underutilized stadiums. Marginal bowls come and go, just as they did in the 1920s, and their host cities increasingly mean less and less other than their potential ties to the corporate sponsor.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.