Pa Corbin and A Trick Well Executed

Football centers have snapped the ball with their hands since 1893 or 1894, but they snapped it with their feet until then or kicked it forward to put it in play. Beginning in 1876, football followed slightly modified Rugby Union rules, so play largely amounted to a mass of players on either side pushing, pushing, and kicking the ball toward their opponent's goal. Play was continuous; there wasn't a designated player who started play by snapping the ball.

When football moved to the rule of possession and the controlled scrimmage in 1882, a forward (lineman) initiated play by kicking it forward or snapping it back with his foot. But as football moved to structured plays on offense, most teams switched to snapping the ball back rather than kicking it forward to initiate play. An 1888 football primer described the process of initiating play, saying:

[After a player is tackled,] the player shouts "Down" to the referee who sees if he has the ball, and if so orders hostilities to cease. The ball is not lifted from the ground, and the man who had it or some one else selected by the captain puts his foot on it while another man from the same team kneels down just back of the ball... The rival rushers are close at hand ready to seize the ball should the player's foot slip off it. Suddenly, after a feint or two, the ball is "snapped back" to the man kneeling, who seizes it and throws it further back [to another back.]

'College Kicker,' Morning Call (Paterson, NJ), November 14, 1888.

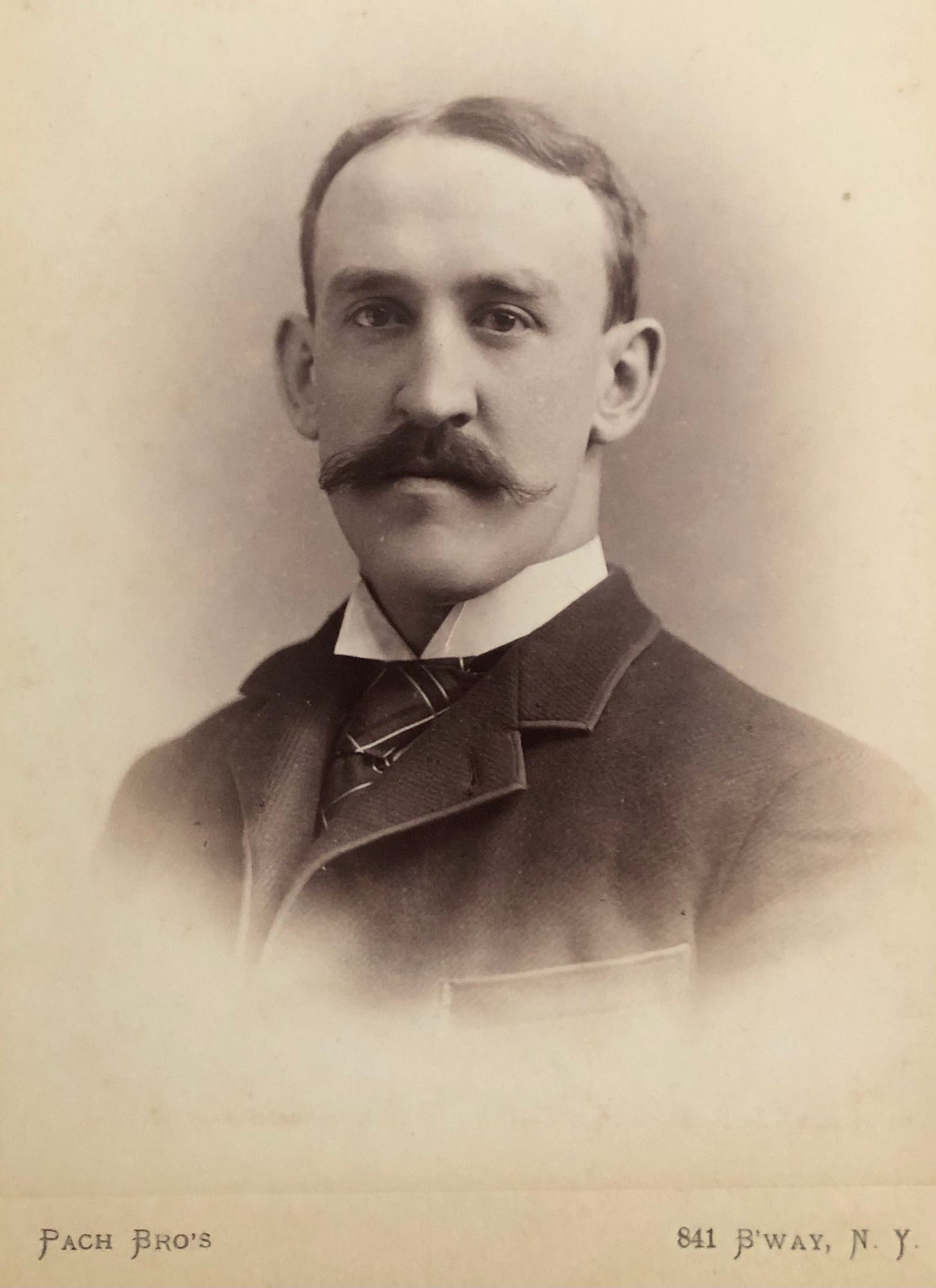

Most teams designated a particular player to snap back on every play, but it remained legal for the "snapperback" to kick the ball forward if he chose to do so. Although defenses almost universally place a man across from the snapperback, the snapper might see an opening, kick the ball forward a few feet, pick it up, and run with it. Certain players, such as Yale's William Herbert "Pa" Corbin, were adept at this play, and, despite being considered gigantic at 6' 2", 185 pounds, he was a fast, effective runner.

The problem with kicking the ball forward was its lack of predictability. Defenders shifted about, and the ball bounced in funny ways, so there was no guarantee that the offense would recover and advance the kicked ball.

Corbin’s 1887 Yale team saved the most ingenious use of his kicking privilege for the last game of the season, on Thanksgiving Day versus Harvard at the Polo Grounds. During the first half, Yale had earned a field goal, and, after getting the ball back:

Yale again had the advantage, and, barring a fine run of Porter's, made steady progress till Corbin, by a trick well executed, broke through the centre of the rush line and touched down behind the goals.

'The Yale Boys Winners,' Philadelphia Inquirer, November 25, 1887.

What was the trick well executed? On the play, Yale lined up as usual with Corbin at snapperback, George Woodruff at right guard, and Harry Beecher at quarterback. (Beecher's great aunt was Harriett Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom's Cabin.) Rather than snap it back or kick the ball several yards forward, Corbin dribble-kicked it to Woodruff at right guard, who picked it up and handed it back to Beecher. While the exact player movements of the trick play are lost to time, Beecher somehow gave the ball to Corbin, who ran for the touchdown, contributing to Yale's 17-8 victory over Harvard.

Although the risky play worked and enhanced Pa Corbin's already significant fame, it signaled the end of snapperbacks kicking the ball forward. Instead, teams almost universally snapped the ball, preferring to rely on more structured plays to win games. A few years later, they transitioned to centers snapping with their hands.

Following the transition, kicking the ball forward became one of football's vestigial rules, remaining on the books long after the tactic was out of favor. As a result, the rugby tactic of kicking the ball forward to start play overlapped the forward pass in the rule book for four years, remaining legal through the 1909 season.

FYI: If the story of Corbin kicking the ball forward sounds familiar, it was mentioned in the series covering football's original 64 rules of 1876.

Click here for options on how to support this site beyond a free subscription.

The Elis matrickulated the ball down the field!

Isn't Woodruff above Beecher, wearing the tight blue 'Y' jersey? ..