Pete Overfield and Center Play in 1897

Raise your hand if you are familiar with Pete Overfield's game. If not, you soon will be.

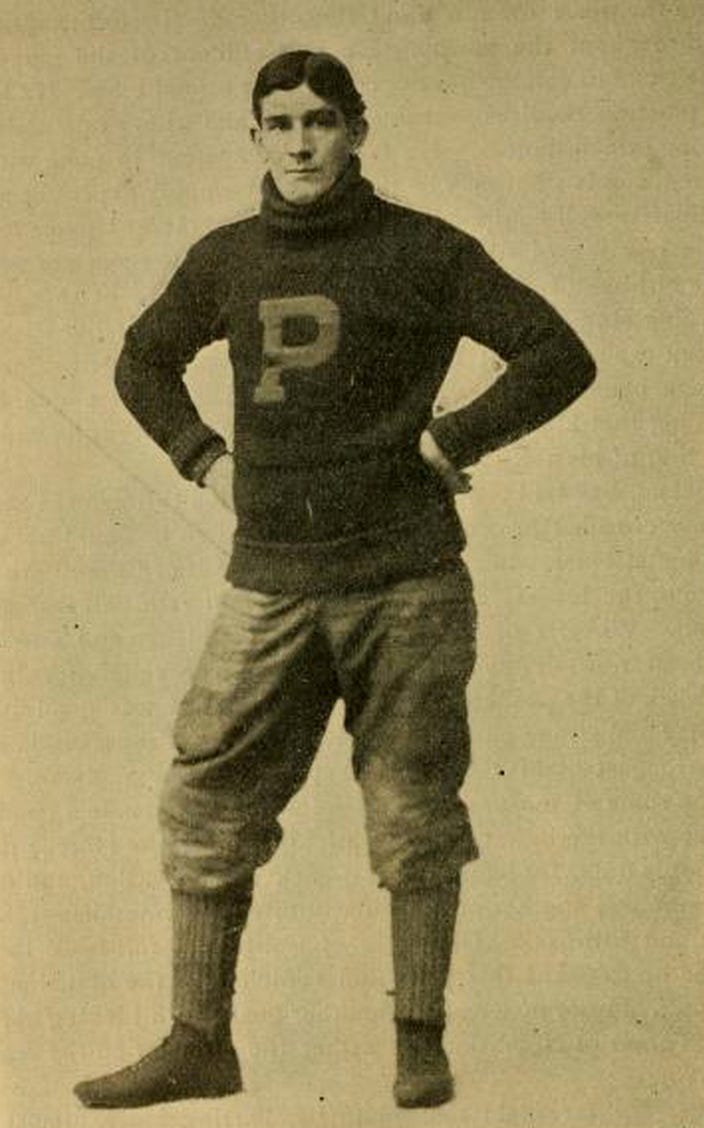

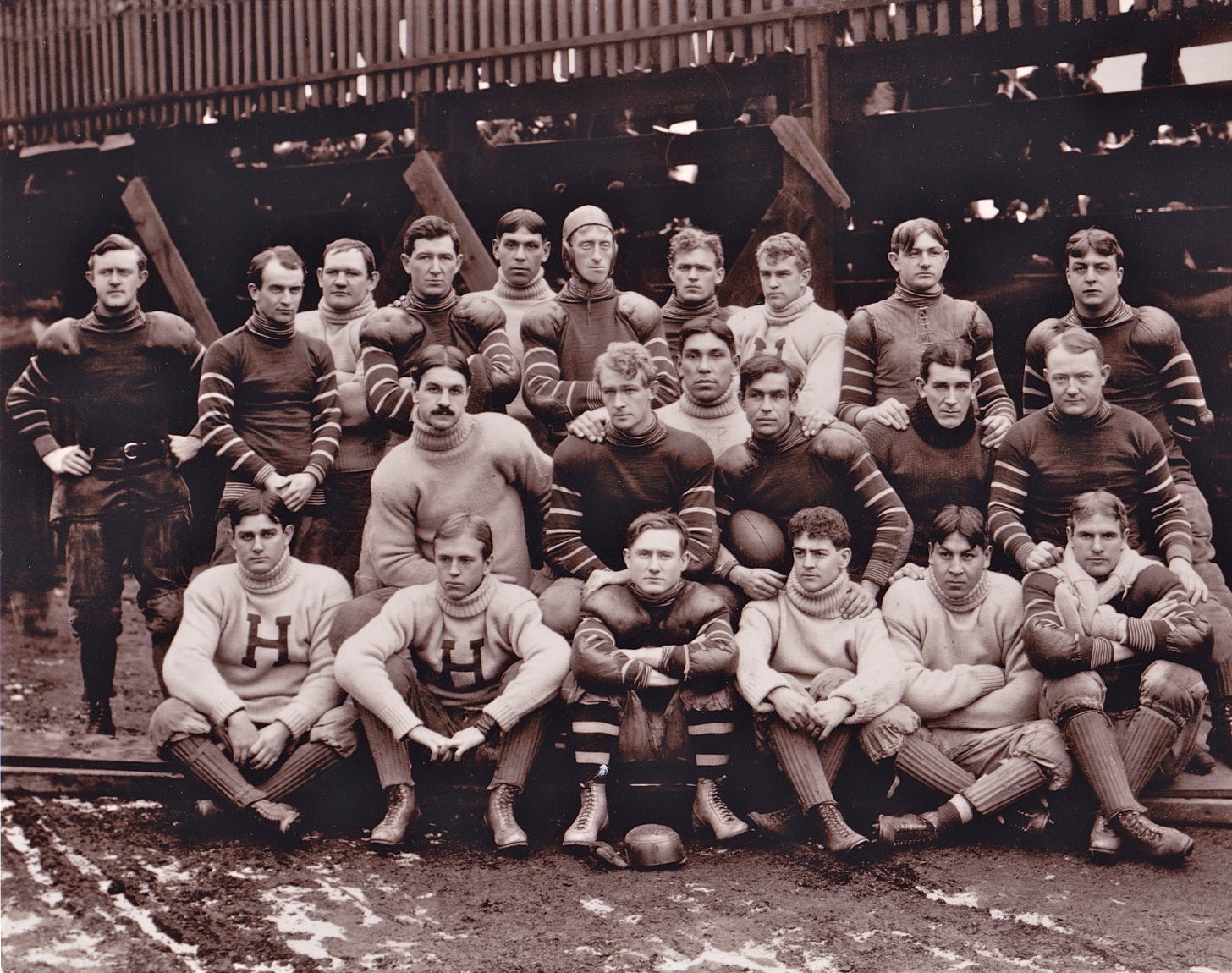

Overfield was a two-time All-American at Penn, joining Camp's first team in 1888 and 1889. After playing two years at left guard for Mansfield Normal, Overfield enrolled at Penn, becoming an immediate starter at center for teams that went 14-1, 15-0, 12-1, and 8-3-2 under George Woodruff, earning a national championship in 1897.

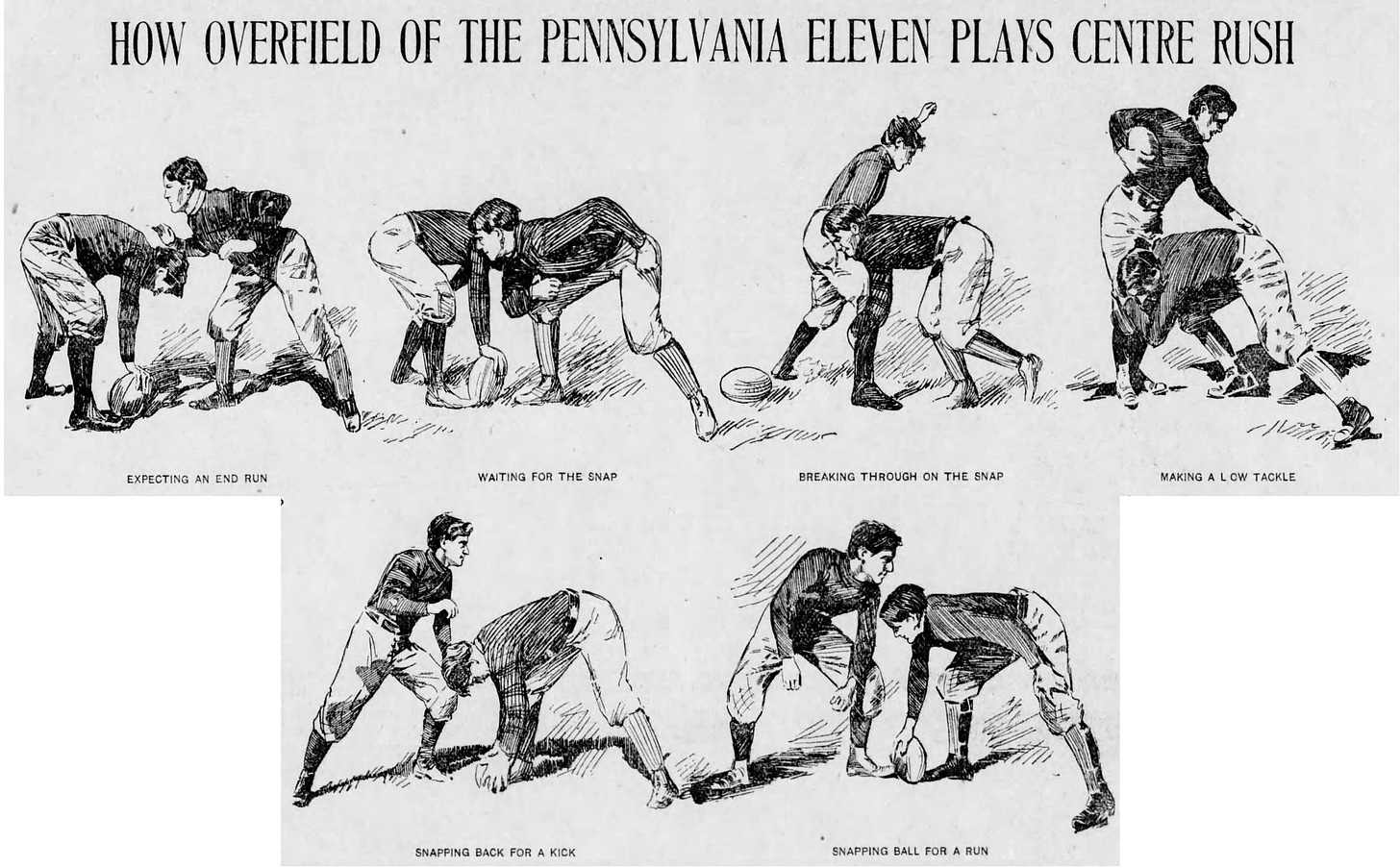

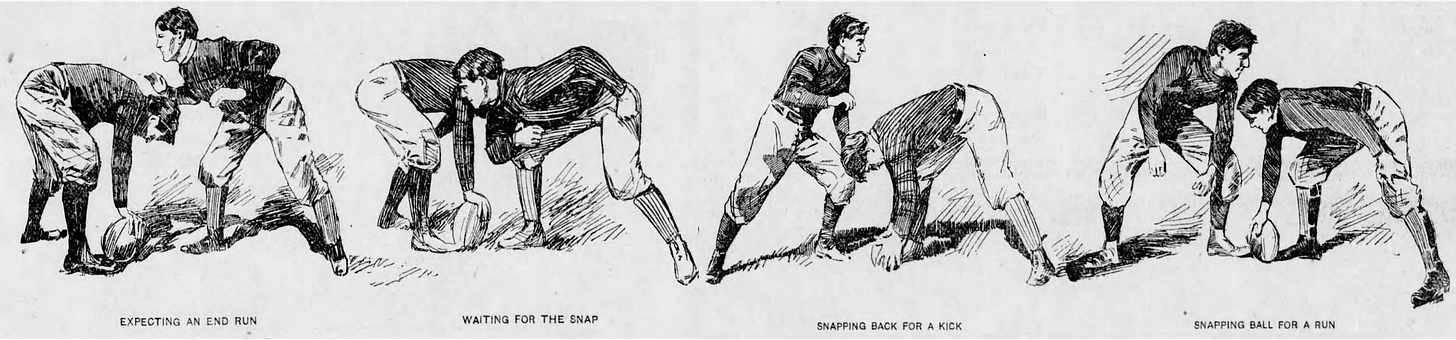

Early in his sophomore season, the Philadelphia Times published a set of illustrations showing his technique at center (or centre as they spelled it then), which provides a launch pad to discuss the nature of line and center play at the time. Back then, linemen were collectively called forwards or rushers, and the center was referred to as the center rush, snapperback, or snapback.

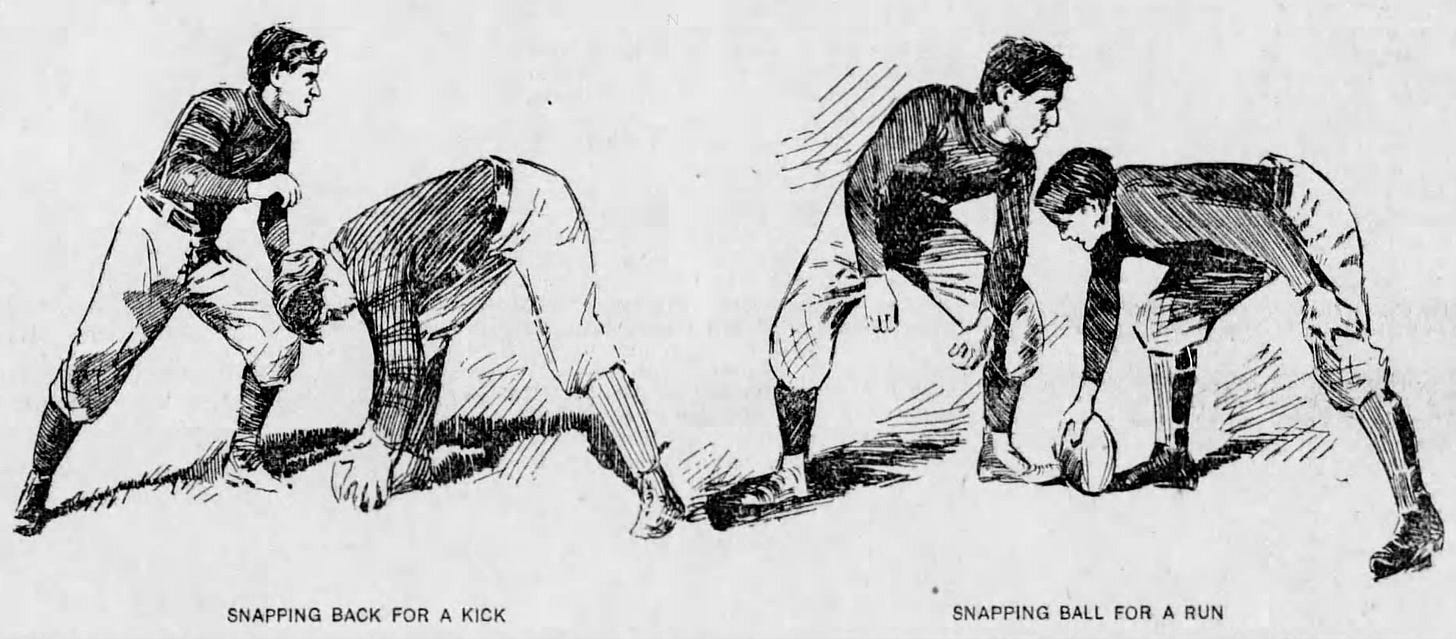

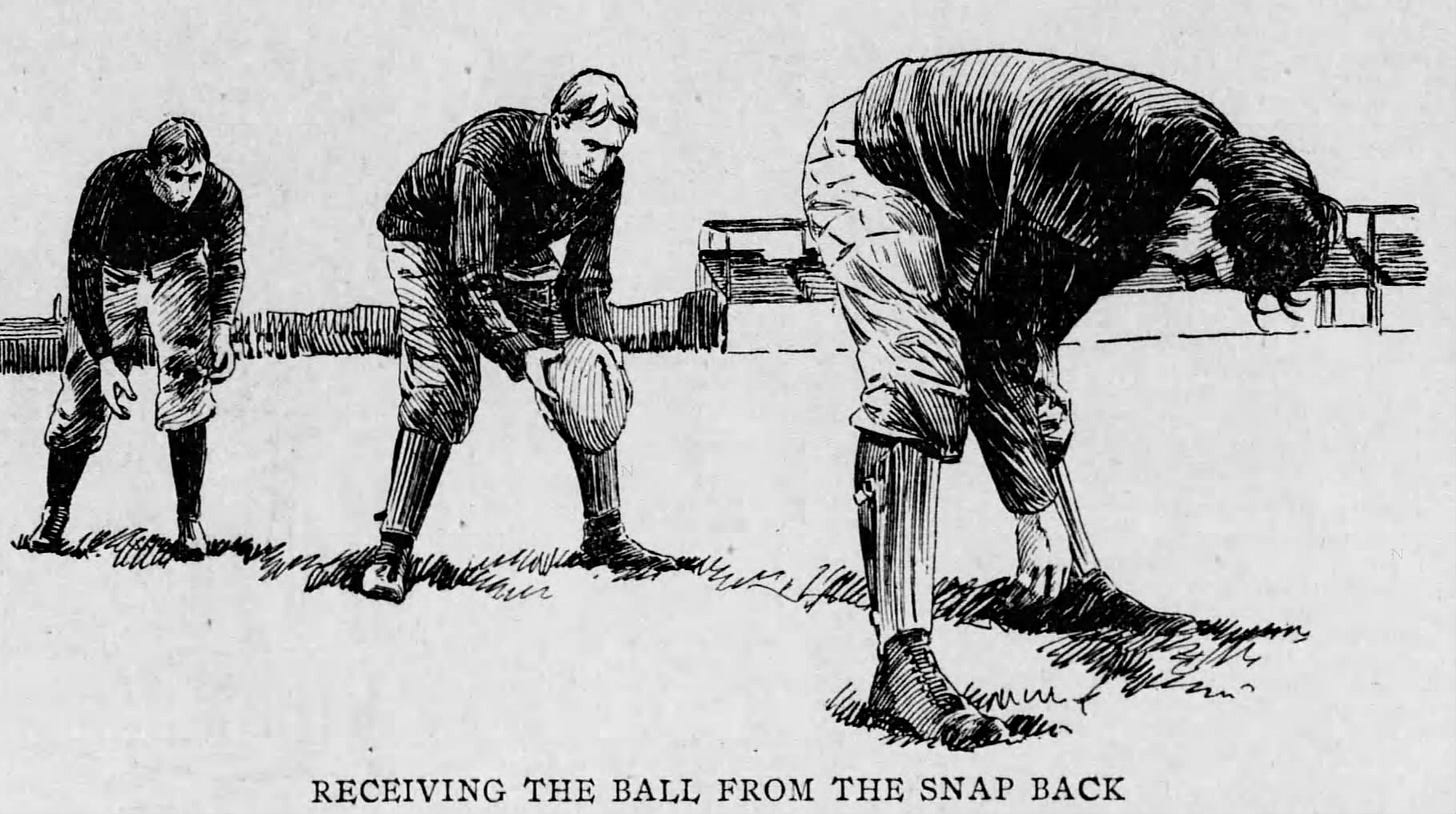

In the 1890s, everyone played both offense and defense, so it is unclear whether Overfield is the offensive center or the defensive center in some of the illustration below. Either way, several things pop out.

First is the proximity of the offensive and defensive linemen. The neutral zone created in 1906 kept everyone, except the offensive center, behind the offensive or defensive lines of scrimmage that ran through either end of the ball. The two illustrations on the top left and the two at the bottom show the defender overlapping the ball. When seven linemen took such stances, the officials had difficulty seeing pre-snap rough play.

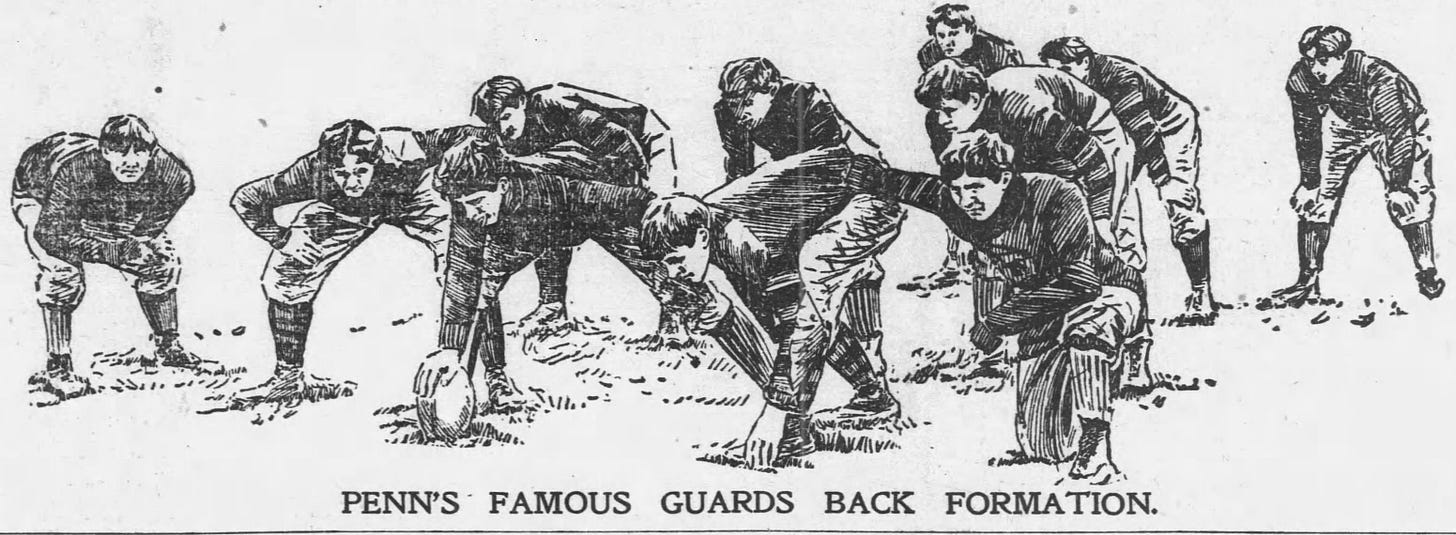

The same illustrations show the defensive center in a standup or squatting stance. Football was in the midst of a transition then, with some linemen standing, others squatting, and here and there, linemen taking three and four-point stances mirroring sprinters in track. The illustration of Penn's Guards Back formation, with both guards aligned in the backfield for mass play purposes, shows the interior line using a mix of styles.

Centers snapped the ball with their feet until 1892, when snapping with the hands became legal. Even when snapping with the hands, it took a few years for center to lift the ball off the ground rather than roll it back, as they had with their feet. Overfield appears to use both approaches.

The illustration of the snap for a run shows him using one hand, which likely sent the ball tumbling end over end along the ground to the quarterback, who squatted several feet behind or to the side of the center. The illustration of the snap for a kick shows him using two hands. Since the spiral snap did not arrive until 1910, the two-handed snap would have sent the ball tumbling end-over-end through the air or floating "dead ball" style.

Interestingly, the description of Penn's 1897 victory over Harvard mentions Overfield snapping the ball to Morice, Penn's right halfback, who lay on the ground as he held for the fullback's field goal attempt. All field goal attempts were made by dropkick until 1896, when two brothers at Otterbein developed the center snap for placement kicks on field goals. I previously understood that the holders squatted in place to catch the ball before setting the ball on the ground. Apparently, Penn snapped to a holder laying on the ground. This is the first time I've encountered a description of that approach on a field goal attempt, although the prone over-under technique was the norm for free kicks, such as extra point attempts.

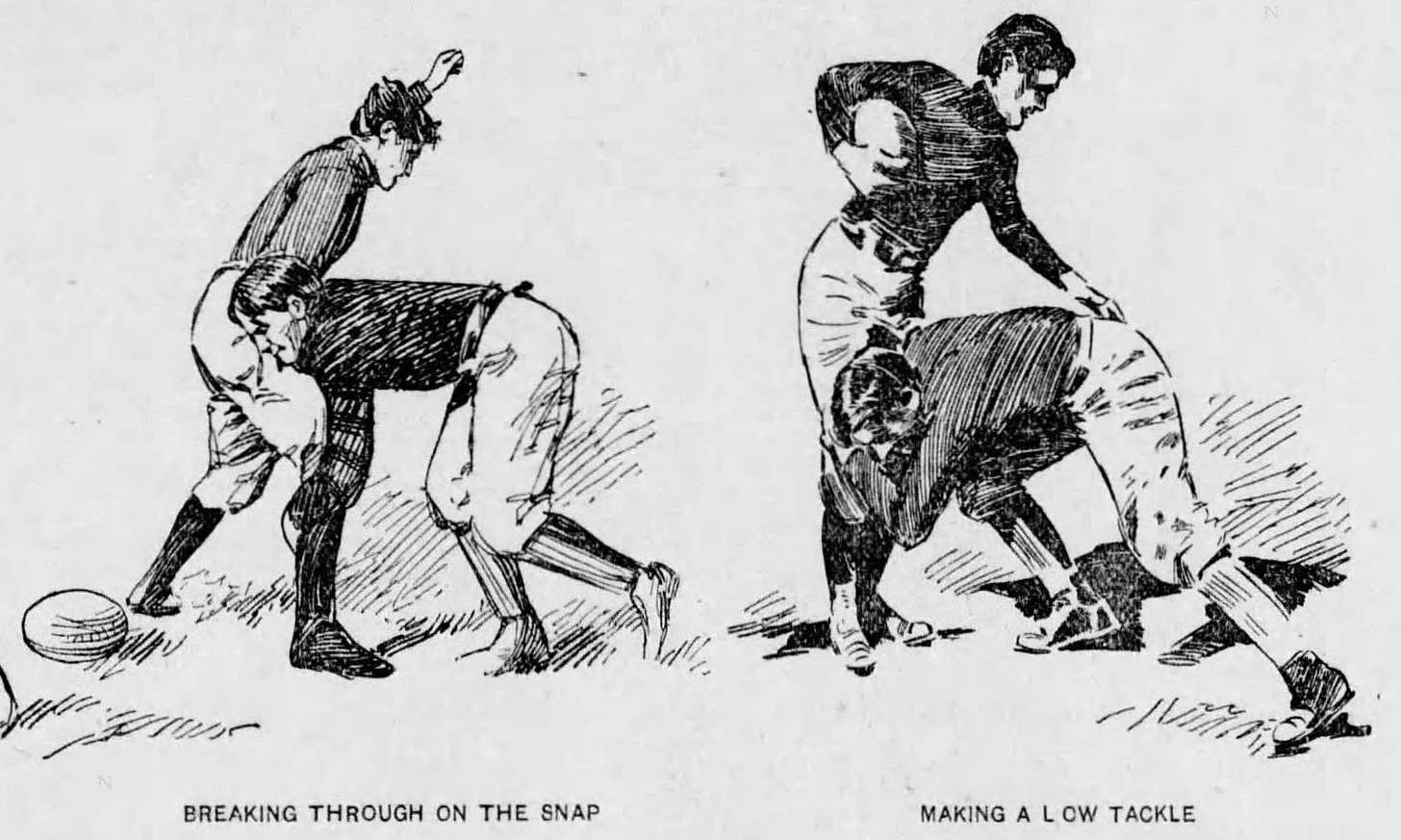

I'm not sure what's going on in the "Breaking Through On The Snap" illustration, while the low tackle illustration makes sense, but is not particularly interesting.

Overfield ended his playing days with the Homestead Library and Athletic Club in 1900 and 1901, an early pro team that claimed the 1901 national professional championship.

A final issue is a question for readers. Like many newspaper illustrations of the time, the illustrations above were hand-drawn from photographs, indicating a technological limitation or cost issue prevented them from printing the pictures themselves in the papers. Newspapers began printing photographs a few years later, so if anyone knows what changed around the turn of the century, please provide an explanation.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to donate a couple of bucks, buy one of my books, or otherwise support the site.

From the Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/collections/world-war-i-rotogravures/articles-and-essays/the-rotogravure-process/

I want to say I read somewhere that a new style high speed camera came out about that time whose faster shutter speed allowed for clearer images as the subject matter didn't have to stay still as long. Newspapers were buying these and using their use as a marketing tool to sell dailies.