Pop Warner and the Bizarro World of Early Forward Passing

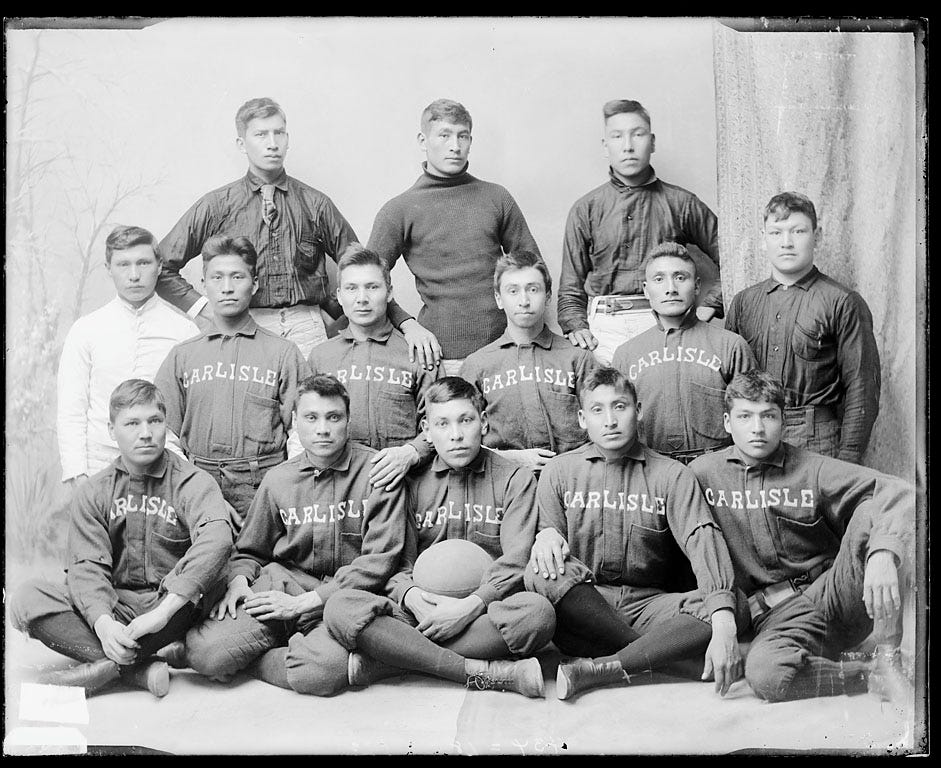

Dickinson College is not a place you’d think of as a source of information on football history. Yet, its library and archives are a treasure trove of information about the Carlisle Indian School and its football team. Dickinson sits in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and its library’s Archives and Special Collections houses the Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center, among other materials.

The library staff makes periodic trips to the National Archives to digitize Carlisle-related materials, receives donations, and purchases other items for the collection.

Included in their collection are 18 pamphlets from the 1908 edition of Pop Warner’s correspondence course, which he sold to coaches nationwide. He published updated materials in 1909 and 1910, before issuing a book in 1912. Last week, I paid a reasonable fee to have those pamphlets digitized, so the digital images are now available to anyone interested in obtaining them. (If that includes you, see end of story.)

I’ll likely pull multiple stories from the pamphlets, including today’s, which concerns the early forward pass. Warner coached Cornell in 1906, where he made little use of the forward pass, but Carlisle had passed more than most teams in 1906, and when Warner returned to Carlisle in 1907, they continued throwing the ball.

Unlike many who argued that the overhand spiral was difficult to learn due to the size of the ball, Warner claimed that most of the Carlisle squad could throw the spiral for distance. So, Warner’s pamphlet on “Offense” pamphlet includes about 20 play diagrams, including a handful of forward passes, such as the one below which shows a pass thrown from Carlisle’s punt or dropkicking formation.

The forward passing rules of 1908 were quite different from today’s. Among other differences, you had to throw passes from five yards to the right or left of center, and could not throw the ball over the interior line. Hence, the diagram shows the passer rolling to the right.

Other rule differences included allowing offensive linemen to run downfield on forward passes, and there was no offensive or defensive pass interference. The result was that teams designed plays in which linemen and others ran downfield to block defenders while the pass was in the air, often encircling a designated receiver and fending off defenders who tried to knock down or intercept the ball.

Warner’s play no. 17 is a variation on that theme. Rather than identifying an intended receiver, which assumed the passer could throw the ball with sufficient accuracy to reach the intended receiver, play no. 17 had multiple eligible receivers head downfield, and whichever one was closest to where the ball would land claimed it, as baseball players claim pop flies.

As the play description notes:

...the three backs and end string out down the field, so that one of them is sure to be near the spot where the ball is thrown. When one of them is sure he can get under the ball he yells “I have it,” and the others protect him by blocking off opponents.

The design suggests that while the Carlisle players were able to fling the ball a reasonable distance downfield, the accuracy of the throws was suspect, so Warner designed the play to account for the inaccuracy. It was akin to today’s Hail Mary pass, except the offensive players who did not claim the pass became blockers while the pass was in the air.

Warner had to remove play no. 17 from the next edition of his correspondence course because the 1909 rulemakers made pass interference illegal, though the rules still allowed players to push or run through their opponents when attempting to catch the ball.

The early forward-passing rules and play designs were quite different from today’s, and this example play designed by a forward-passing innovator illustrates that point. For those interested in more tales of the first ten years of the forward pass, check out my new book, When Football Came To Pass.

Those interested in Warner’s 1908 correspondence course pamphlets can submit a request to archives@dickinson.edu. For now, they’ll provide a link to download the materials. As time allows, they’ll make them available for direct download online.

If you enjoy Football Archaeology, become a free subscriber or a paid subscriber for $5/month or $50/year.