Pounding the Rock: Football at Joliet's Stateville Penitentiary

The Longest Yard and The Dirty Dozen are redemption stories based on the belief that convicts, like everyone else, have core goodness that is revealed in the right circumstances, under the right leadership. The Longest Yard also celebrates sports as a great equalizer in that everyone, regardless of background or circumstances, competes on an even playing field. Given the popularity of both movies, it is no surprise that Americans of the 1930s found the story of the Stateville Penitentiary football team appealing.

Stateville opened in 1925 just north of Joliet, Illinois. Often referred to as New Prison, it supplemented Joliet’s Old Prison, which most of us know as the onetime home of Jake Blues of The Blues Brothers.

A few years ago, I stumbled upon a 1930s article concerning new eligibility standards for football-playing inmates at Stateville. The syndicated story was picked up by newspapers across the country. Over the next few years, follow-up articles told the tale of those playing for State Pen rather than Penn State.

Football played by convicts in a state penitentiary may seem odd, but it was consistent with similar movements in American colleges and universities after WWI. One of the takeaways from the war was that the enlistees and draftees pouring into the military during WWI were physically lacking, which contributed to the military's emphasis on camp athletics programs to hammer them into shape. After the war, many criticized America's colleges and high schools for emphasizing varsity athletics at the expense of sports for the broader student bodies. The criticism led to the initiation and growth of intramural programs.

A few years later, programs for the physical and mental well-being of students transferred over to those incarcerated in America's prison systems. And since intramural is a combination of intra or 'within,' and murus, the Latin word for 'wall,' intramural programs for prisoners made perfect sense.

With that as a backdrop, Stateville Penitentiary announced in late 1931 plans for a new intramural sports program among the inmates. Basketball and baseball were the first target sports -cross country and pole vaulting were not- and they added football for the 1932 season. As with dorms on a college campus, teams formed at the cellblock level and played a round-robin schedule. Partway through the 1932 season, however, they decided to field an all-star team, hoping to play outside competition. Home games only, of course.

Stateville was a maximum-security prison; housing Baby Face Nelson and Leopold and Loeb, the convicted child murderers in the 1920s version of the crime of the century. Marty Durkin was another Stateville resident. Incarcerated for the 1925 murder of an FBI agent, the first federal agent killed in the line of duty, Durkin evaded authorities for several months during a search overseen by the new FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. Since killing a federal agent was not yet a federal crime, Durkin, who committed his crime in Chicago, was tried and convicted under Illinois law and sent to Stateville. Like Leopold and Loeb, Durkin gained a national reputation while on the lam, but unlike Leopold and Loeb, Durkin played a pretty good brand of football, allowing him to start at guard for the Panthers.

Finding teams willing to play Stateville was not easy in 1932, as few were willing to face a literal murderers' row. We can assume many teams turned down the opportunity to play the Stateville Prison Panthers, but the Cabery All-Stars raised their hands and agreed to play an away game at Stateville. Cabery was (still is) a small farm town fifty miles south of the prison that fielded a town football team from 1910 to 1934. Local legend says they once played and beat the Decatur Staleys, who soon morphed into the Chicago Bears. While that story is solidly embellished, the Cabery team’s willingness to play a Stateville demonstrated they were unafraid of playing in a tough environment.

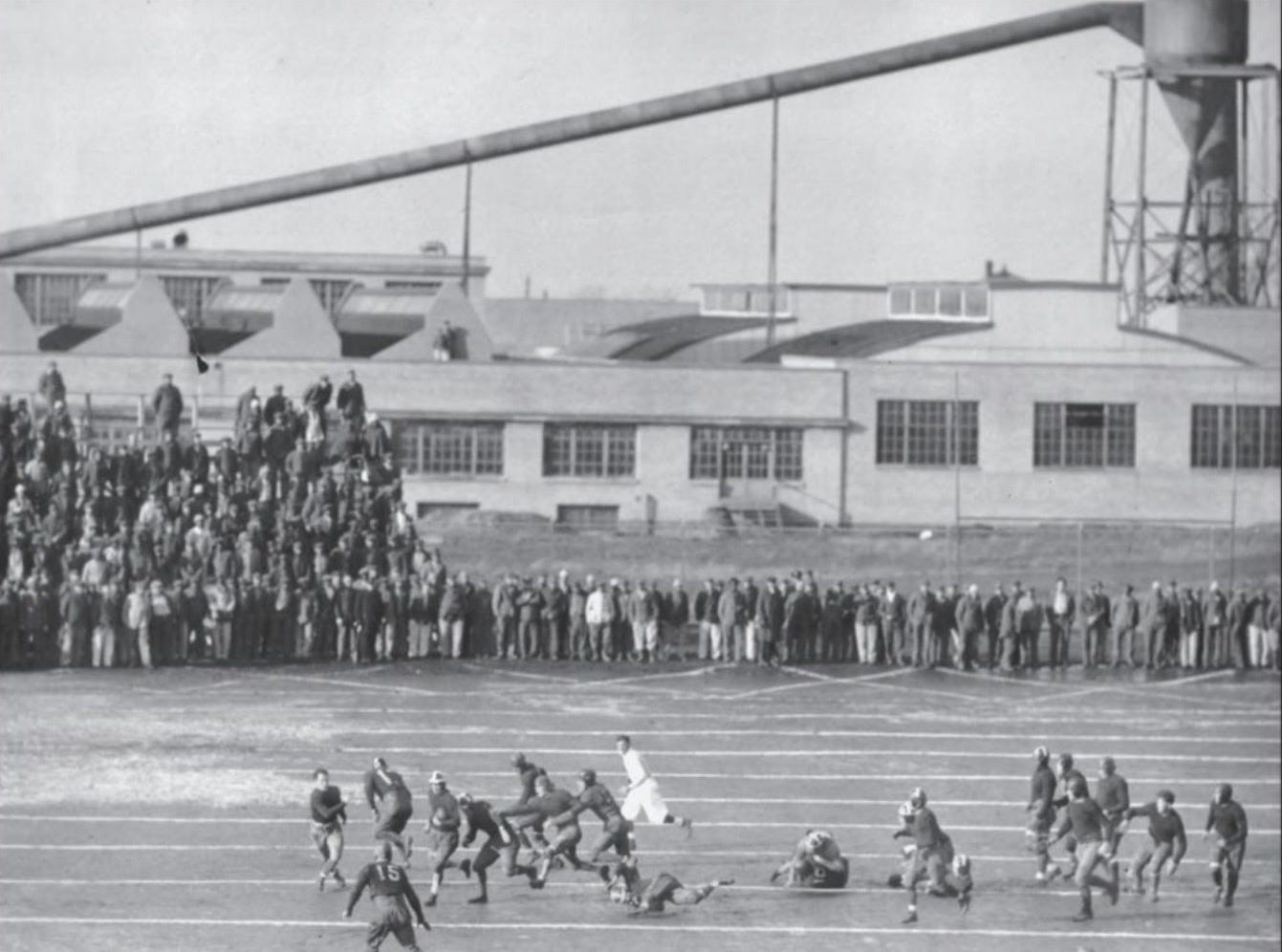

The teams scheduled a game for the day after Christmas 1932. Newspaper accounts are few, but we know 3,000 prisoners, a few guests of the warden, and various reporters attended the game on a cold but sunny day. Unfortunately, the thin layer of ice covering the field at the game's start gave way under the spikes and tumbling bodies revealing puddles, and the field soon turned into a swamp, so neither team threw a forward pass.

The game ended in a 0-0 tie. It was a clean game with only three penalties, none for roughing. Thankfully, the redemption story tied to the game resulted in the presence of a newsreel film crew, and a portion of the film is available on YouTube. Shot from a tower or rooftop in the corner of an end zone, the prison's furniture factory looms over the field beyond the far end zone. Besides the game action, the film crew captured numerous crowd shots and parts of the home crowd wandering onto the field after the game while others head inside to warm up.

Perhaps due to the field conditions or the first game ending in a tie, Cabery returned for a second game two weeks later, with the prisoners earning their stripes in a 12-6 win.

Whether it was the season-ending win, the media attention, or the opportunity to have some fun, interest in playing Panther football increased in 1933. More than 250 tried out for the team, leading prisoners new to Stateville to complain that those serving long sentences, like Durkin, would not give up their varsity positions. As a result, the warden ruled that prisoners would be ineligible to play after three consecutive years on the team, creating another story that gained national attention.

Information about the 1933 team is unavailable, but the 1934 team played a series of semi-pro teams from northern Indiana, Chicagoland, and downstate Illinois, winning ten straight. The Panthers outscored their opponents 503-0, which tells us they had some talented players carrying the jailhouse rock.

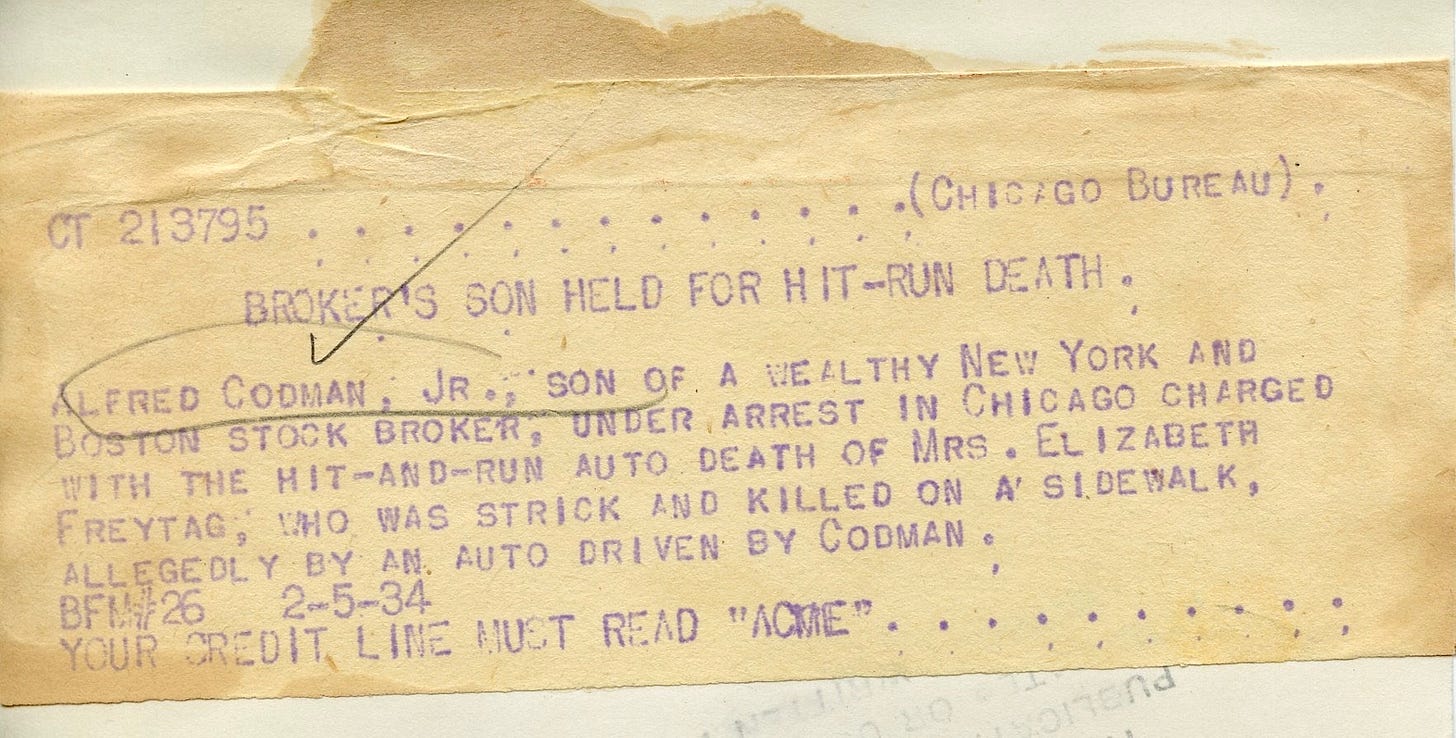

Repeating that level of success in 1935 was considered a tall task due to several key starters graduating (aka earning parole), so they pinned their hopes on a new prisoner, Alfred Codman, Jr. Born into a wealthy Boston family, Codman was found guilty of manslaughter in the death of a Chicago pedestrian he struck while driving drunk, so Codman found a new home at Stateville in January 1935.

Codman brought something new to Stateville football. A dozen years earlier, Codman started at center for Harvard's 1921 freshman team and was a varsity reserve in 1922, leaving school after his sophomore year. That made him the only inmate at Stateville with playing experience at Harvard and qualified him to be the varsity head coach for the 1935 season.

Under Codman's leadership, the team carried on its winning tradition, recording its eleventh and twelfth consecutive wins against two semi-pro teams from Gary, Indiana. However, the next week, they ran into the buzzsaw known as the Culbertson Athletic Club of Chicago, who outfought the Panthers and won 13-0. Stateville's loss and the disruption of its win streak seem to have ended the nation's fascination with the team since their game scores the rest of the 1935 season went unreported.

The close of 1935 saw Codman's time at Statesville also come to an end. A privileged man, he received a governor's pardon in December and returned to Boston, where he spent the rest of his life outside of prison walls.

The 1935 season appears to have been the last in which Stateville played outside competition. Reports of 1936 games are not available, and the warden formally announced Stateville would not face outside teams in 1937. The 1938 death of a prisoner from injuries suffered in intramural football likely ended any chance of reviving the external games.

So, the Stateville football story ended soon after it began. While prison ball had little impact on football generally, the story appealed to an America experiencing tough times. It reminded them that everyone deserves a second chance, there is good in everyone, and that dreams sometimes come true. That’s a pretty good set of takeaways from any story.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.