Remembering John Lockney: Football’s Forgotten Man

Excluding the logos and field numbers that vary from location to location, the standard football field has 385 stripes, and 83 percent of those stripes are due to John Lockney, football's forgotten man.

Today would be Lockney's 107th birthday and it is the time for his contribution to football to be recognized, particularly because Lockney was not a player, coach, official, writer, or involved in managing a team. Instead, he was a normal fan looking to improve the football experience.

Here's what he did.

Like everyone else at the time, Lockney watched football on fields that were barren compared to today. Before 1954, football fields had sidelines, end lines, goal lines, yard lines spaced five yards apart, and two hash marks intersecting each yard line. Some had stripes near each goal line marking the spot for extra point attempts. Some even had yardage numbers. Many did not.

Two game elements that bothered Lockney were how often officials brought the chains onto the field and how frequently they spotted the ball incorrectly when, for instance, it returned to the previous spot following an incomplete pass. Lockney did not view officials as incompetent; he thought they needed assistance. He saw the problem as akin to using a ruler marked only with inch lines -no half, quarter, or eighth-inch lines- and having to measure distances to the half inch or quarter inch. The tool did not match the task.

So, early in the 1954 season, Lockney approached the local high school in Waukesha, Wisconsin, with the idea of adding short stripes on the field parallel to and between the yard lines in the hash mark area and along each sideline. The school officials liked the idea, so Lockney created a form or stencil and enlisted the help of a few buddies to mark the local field. First used for a Friday night high school game, his Lockney Lines were there the next day when Carroll University met UW-Whitewater on the same field.

Lockney Lines were an immediate hit. Fans and announcers could better judge the yardage gained or lost on plays, while officials more easily spotted the ball, particularly after penalties or incomplete passes on the other side of the field. Lockney Lines also reduced the need for officials to bring the chains out for first-down measurements.

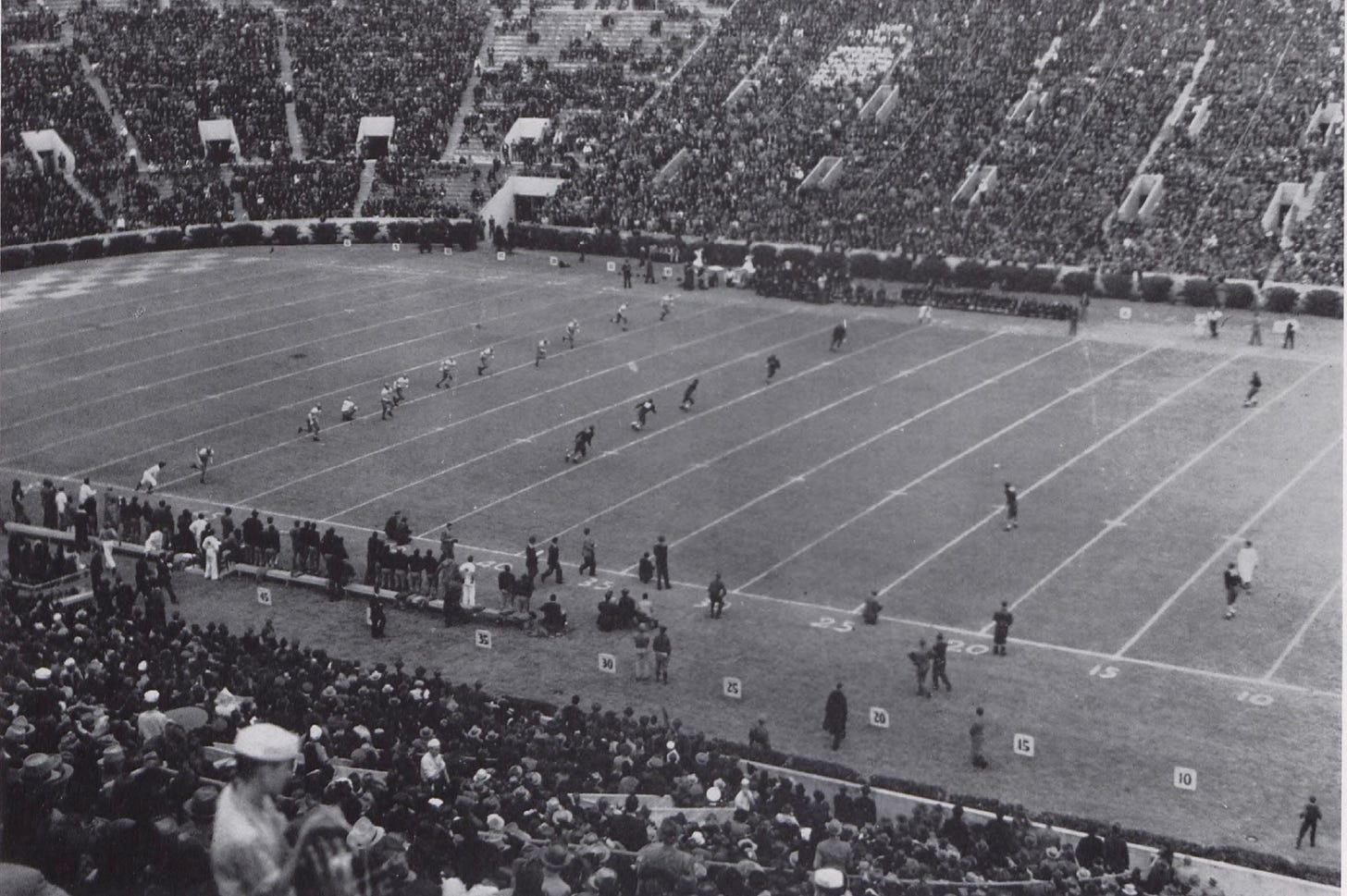

Lockney then convinced the University of Wisconsin to add his lines for a nationally televised game against Rice. With only one college game televised each week at the time, the game between the #3 Badgers and the #11 Owls drew a large TV audience, and the Lockney Lines were a hit once again. Television viewers, announcers, and others praised the innovation and the word spread. Lockney Lines appeared here and there, with the Green Bay Packers adopting Lockney Lines in 1955. They proved so popular the college rules committee made them mandatory for the 1956 season.

Note 2 in the lower right of the 1957 version of the Diagram of Field indicates the NCAA considered the outer Lockney Lines optional.

The 1960s was a tumultuous decade, even impacting Lockney Lines. Until 1966, most everyone painted the outer Lockney Lines outside the sidelines, not inside where they sit today. (Take another look at the images above if you have not picked up on the difference.) However, that location became problematic when the Kansas City Chiefs spiced up their field by surrounding the gridiron with a white border, the same color as the white Lockney Lines.

When Kansas City's groundskeeper, George Toma, gained responsibility to prepare the field for Super Bowl I played several weeks later, he kept the outer Lockney Lines beyond the sidelines but painted them red and blue. Before the 1968 season, the NFL recommended surrounding the field with a white border for all games, so teams began moving the outer Lockney lines inside the sidelines where they remain today.

The NCAA allows but does not require a white border around the field. Still, the 1986 recommendation to paint white the area between the sidelines and the coaches' boxes effectively forced college teams to move the Lockney Lines inside the sidelines.

Clearly, Lockney Lines did not revolutionize football, but they made officiating easier and more accurate. It also made watching football easier on fans’ eyes. We now take Lockney Lines for granted, just as the football world has taken John Lockney's contribution for granted. We don't even give him credit for his invention. We credit certain rules to the player or coach that brought them about, yet the NCAA rule book refers to Lockney Lines as "short yard-line extensions." What better way to honor the Average Joe or Average John in this instance than to call the lines by their real name, Lockney Lines?

Who is with me? (Said in your best Belushi voice.)

If you think John Lockney should receive his due, share, copy, retweet, and otherwise send this story to others, and send a quick message to the NFHS, NCAA, NFL, or CFL. Alternatively, send the message to your favorite team, sportswriter, hall of fame, or anyone else suggesting they refer to those 320 beautiful stripes as Lockney Lines. (Canadian fields have 364 stripes at the current exchange rate, including three outer Lockney Lines along each sideline in the end zone/goal area.)

Write anything you want, but it can be as simple as the following:

Dear ___:

Give John Lockney credit. Start calling them Lockney Lines. See the following link:

Remembering John Lockney: Football’s Forgotten Man

Thanks,

They may not understand why they receive the first few messages, but they'll figure it out if they hear from enough of you. Maybe they will also start calling Lockney Lines Lockney Lines.

Let's get to work. #JohnLockney

The Twitter handles and online Contact Us forms for each organization are below.

NFHS | @NFHS_Org | NFHS Contact Form

NCAA | @NCAAFootball | NCAA Contact Form

NFL | @NFL | NFL Contact Form

CFL | @CFL | CFL Contact Form

Click here for options on how to support this site beyond a free subscription.