Shedding Light on Football’s Early Night Games

Until recently, I thought night football games were rare in football's early days, but a recent investigation uncovered more than thirty games before 1910; half or more occurred indoors. Arena football, it turns out, has been around for a while. Still, despite inadequate lighting systems, most early night games occurred outdoors because night games were a novelty and allowed some fans to attend games that could not do so in daylight.

To understand the challenges of lighting football fields in the 1800s, we'll quickly examine early electrical lighting systems. Thomas Edison pioneered many electrical system elements through his inventions and provided soup-to-nuts systems to power individual factories or homes. Edison also built the first centralized power system in 1882, the Pearl Street plant in New York City. A steam-powered direct current system, Pearl Street powered 3,000 lamps, all of which had to be within one-half mile of the generator because direct current could not be transmitted over distance at the time. By 1890, George Westinghouse and others engineered alternating current systems capable of lighting lamps twenty-five miles from the power source. Even then, the inability to distribute power over greater distances resulted in a power system consisting of independent generating plants, each providing electricity for one factory, trolley system, or city's streetlights. The integrated power grid we take for granted was decades in the future.

Beyond power being available only in pods, the lighting quality was poor. Arc lamps were annoyingly bright, while the typical household bulb in 1890 was one-tenth as bright as those of the 1920s, and the latter was much less bright than today's LEDs. The combination meant early night games needed a nearby power source. The local organizers also had to muster large numbers of lights, the reflectors to direct the light, and the resources to construct a system needed to hang the lights about the playing field. Few locations managed all three.

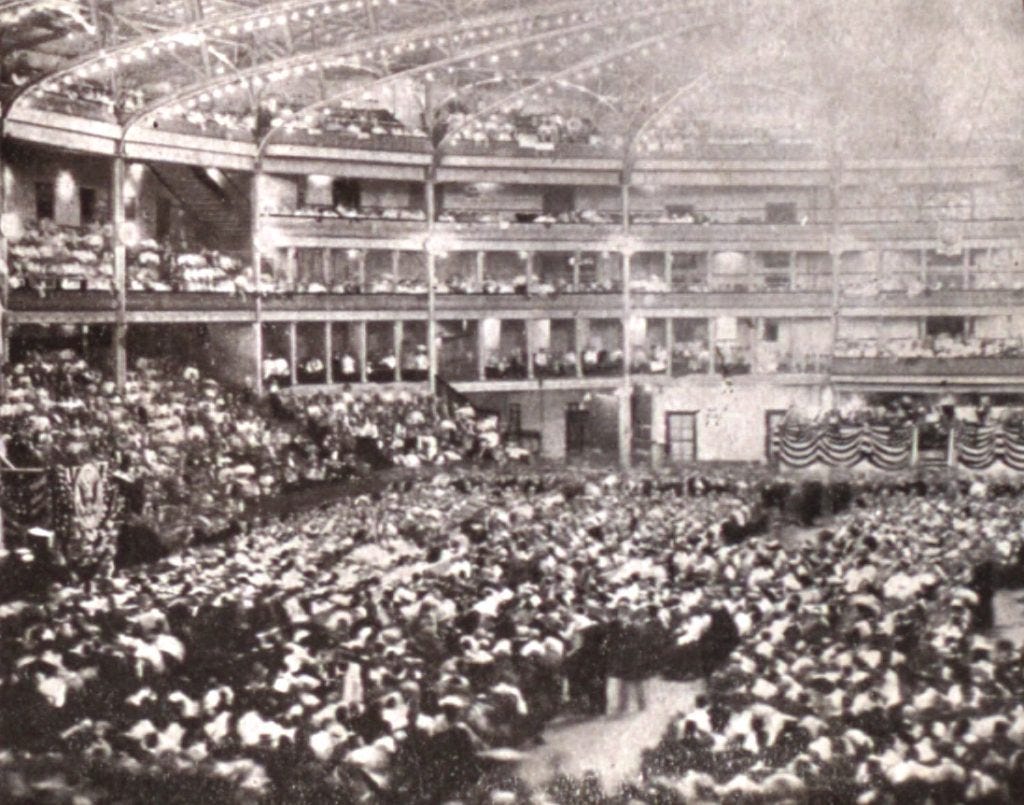

The one group of locations that managed to put it together was the exposition halls emerging in major cities with large windows on their exterior walls and a combination of gas and electric lighting. These exposition halls held political and business conventions along with entertainment events, including sports. For sporting events, they had the advantage of protecting spectators from inclement weather and, due to their lighting systems, the ability to field events at night. In addition, playing under artificial light attracted crowds due to its novelty and because most Americans worked six days per week and were unable to attend afternoon events.

The introduction of indoor football appears to have been an 1889 game played at the Philadelphia Academy of Music between the University of Pennsylvania and the Riverton Club, which four Princeton players supplemented. With an attendance of 2,000, including the season's debutantes and other socialites, the game was a commercial success and athletic failure. Played on a carpeted floor, kicking was not allowed, which meant the game devolved into fistball rather than football. The Philadelphia Inquirer game report describes numerous fistfights and other shenanigans, with the game ending in a 0-0 tie.

The second game played under the lights was an 1891 indoor contest that was part of a multi-sport tournament sponsored by the Staten Island Athletic Club at the second Madison Square Garden in New York City. The tournament included a football game played between the Springfield YMCA Training School -player-coach Amos Alonzo Stagg led the way- and an aggregation team with five Yale varsity players, including Pudge Heffelfinger. Starting just before midnight, Springfield led late in the second half before giving up a late touchdown. Unfortunately for Springfield, the aggregation's goal after touchdown attempt hit the goal post, bounced back onto the field, and was recovered by the aggregation team inside the ten. Under the rules of the day, that gave the aggregation team a new set of downs, and they soon scored a second touchdown to win the game.

The third indoor game came when the Chicago Athletic Association played West Point at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair Stock Pavilion. Pudge Heffelfinger, who had become football's first professional player by then, and other former college stars played for Chicago AA in its 14-0 victory over the Cadets. After that, Chicago hosted other indoor games under the lights, starting with games during the 1893 season in the Tattersall Building and the 1896 Chicago-Michigan game in Chicago's Coliseum. Wisconsin and Carlisle did the same one year later, as did Indiana and Carlisle in 1897. Like porch lights that attract bugs, fans flocked to the indoor night games with the Chicago-Michigan gate exceeding $10,000, the largest in the West to that time.

Our friends in New York City hosted other indoor games over the next decade, including a 1902 tournament involving professional football teams, including the Syracuse Athletic Club that counted Pop Warner among its players. (Indoor games were relatively common in New York City. The following list is not exhaustive.)

What about outdoor football at night? Unlike the exposition halls, outdoor fields lacked walls and ceilings to reflect the artificial light onto the field, so even more light had to be generated artificially. The problem was that while the permanent exposition halls were worth investing significant dollars into their lighting systems, that was not the case when setting up lighting for experimental outdoor games. The result was poorly lit fields.

The 1892 Mansfield State Normal-Kingston Seminary game is often called the first football game played under artificial light, but the 1891 Springfield-Yale aggregation game preceded it. Still, it was the first night game played outdoors. Played under arc lights strung up for a county fair, the game ended in a 0-0 draw when the elevens agreed at halftime that the lighting was too poor to justify playing a second half. So, the Mansfield-Kingston contest was the first half of outdoor football played under artificial light.

The second outdoor game shined the light on the town or high school teams of Chester and Trainer, Pennsylvania, followed a few years later by the Oshkosh Grass Twine Factory-Twin Beach Athletic Club game. Unfortunately, we know little about either contest, the lighting conditions under which they played, or the crowds they attracted. Still, we can surmise the overall result was unsatisfactory since neither played a second night game.

Although outdoor lighting was inadequate for games in the 1890s, it gained use for practices. For example, club teams in Harlem that could practice only at night did so under the glow of street lamps in 1894, while Chicago's Englewood Wheelmen lit their practice field in 1897. At the college level, the Naval Academy practiced under electrical light starting in 1898, and Chicago did the same in 1899. By 1901, Stagg's Maroons used footballs painted white and talked of applying phosphorescent paint, though it is unclear whether they used the glow-in-the-dark ball.

We have more information about the lighting systems used for games after the century turned. Available reports indicate they positioned lights every ten yards on poles just outside the sidelines and goal lines. Such arrangements left the sideline areas better illuminated than the middle of the field. Though some locations indicated they would suspend lights over the middle of the field for the next game, the next game seldom came. Other sites supplemented the perimeter lighting with spotlights or searchlights that followed the field's action, over-illuminating one field area while leaving the rest in relative darkness.

Darkness in the middle of the field was problematic in the 1900 Drake-Grinnell game, yet the teams met again in 1901. The promoters supplemented the lights using those from a recent horse show for the second go-around. Touted as having light comparable to a store, reporters described the lighting as dim and revealed they installed only half the promised 50 arc lights and 400 incandescent lights.

One attempt to solve the lighting problem came at the 1905 Fairmount (now Wichita State)-Cooper (now Sterling) game. Rather than use electrical lights, they strung Coleman gas lanterns around the field's perimeter, which only exacerbated the half-lit, half-dark problem. One reporter failed to see the irony in writing that the game "was a decided success. The only weak point was that in the center of the field, there was a place where the light did not shine strong enough for the spectators to witness all of the plays." Another observed, "The officials were hampered in their work on account of not being able to see the ball," while a third told readers the lighting "…was not sufficient to make the game a success, the umpire and referee not being able to see the mass plays."

A few night games took place between 1906 and 1910. It is unclear whether people recognized the technology was inadequate or whether the rule changes of 1906 had an impact. Either way, night games largely disappeared until the 1920s. Then, following WWI, lighting manufacturers developed products targeted at the athletic market, and their products proved adequate for some schools to schedule night games consistently.

Unfortunately, the author could not locate photographs to illustrate the poor lighting quality at pre-1910 games, so images of games in the 1920s and 1930s must act as substitutes, despite the lighting technologies being substantially better by then. Note: Using images of night games to assess lighting quality is tricky because the quality of an image results from the lighting quality, the camera, and the camera settings.

As the images show, the "improved" lighting conditions of the 1920s remained poor, despite positioning the light posts close to the field where they often stood between the field and the stands. Period stadiums also had loudspeaker poles standing between the field and bleachers, to say nothing of the structural steel and overhanging upper decks obstructing views at the many football games played in major league baseball stadiums.

Poor lighting conditions affected football in other ways. Teams commonly used white footballs for night games; others added white stripes to the tan ball. Even the NFL used a striped ball until 1956 when lighting conditions in their stadiums improved to the point they could eliminate the stripes. Unfortunately, many colleges lacked professional-level lighting, so they kept the stripes, though their aesthetic value now overrides their functional value.

Now, of course, well-lit fields are everywhere, and just as pre-1910 era fans responded positively to the opportunity to watch football after dark, so do present-day fans, though most do so from the comforts of their home.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.