Swede Overesch and the 1916 Atlantic Fleet Playoffs

Many of football's earliest playoff games involved military teams. Civilian teams seldom needed playoffs. They determined league champions by win percentages, and the few postseason games were by invitation only. So, games could end as a win, loss, or tie, and tie-breaking procedures were unnecessary.

The U.S. military took a different approach, especially those Navy boys, who held tournaments to determine their district and fleet champions. Each district represented one or more major ports along the East Coast, each of which had a complement of ships whose football teams played one another. Since pre-WWI battleships had 900 or so crew members, some of whom had played in college, they played a decent brand of football.

One team that played in a Navy football tournament was the 1916 USS South Carolina. Unfortunately, while most Navy tournament teams received decent press coverage, information about the 1916 South Carolina boys is lacking.

The South Carolina called the Philadelphia Navy Yard home in 1916, as evidenced by the building in the background that matches a barracks at the Philadelphia Navy Yard during the era.

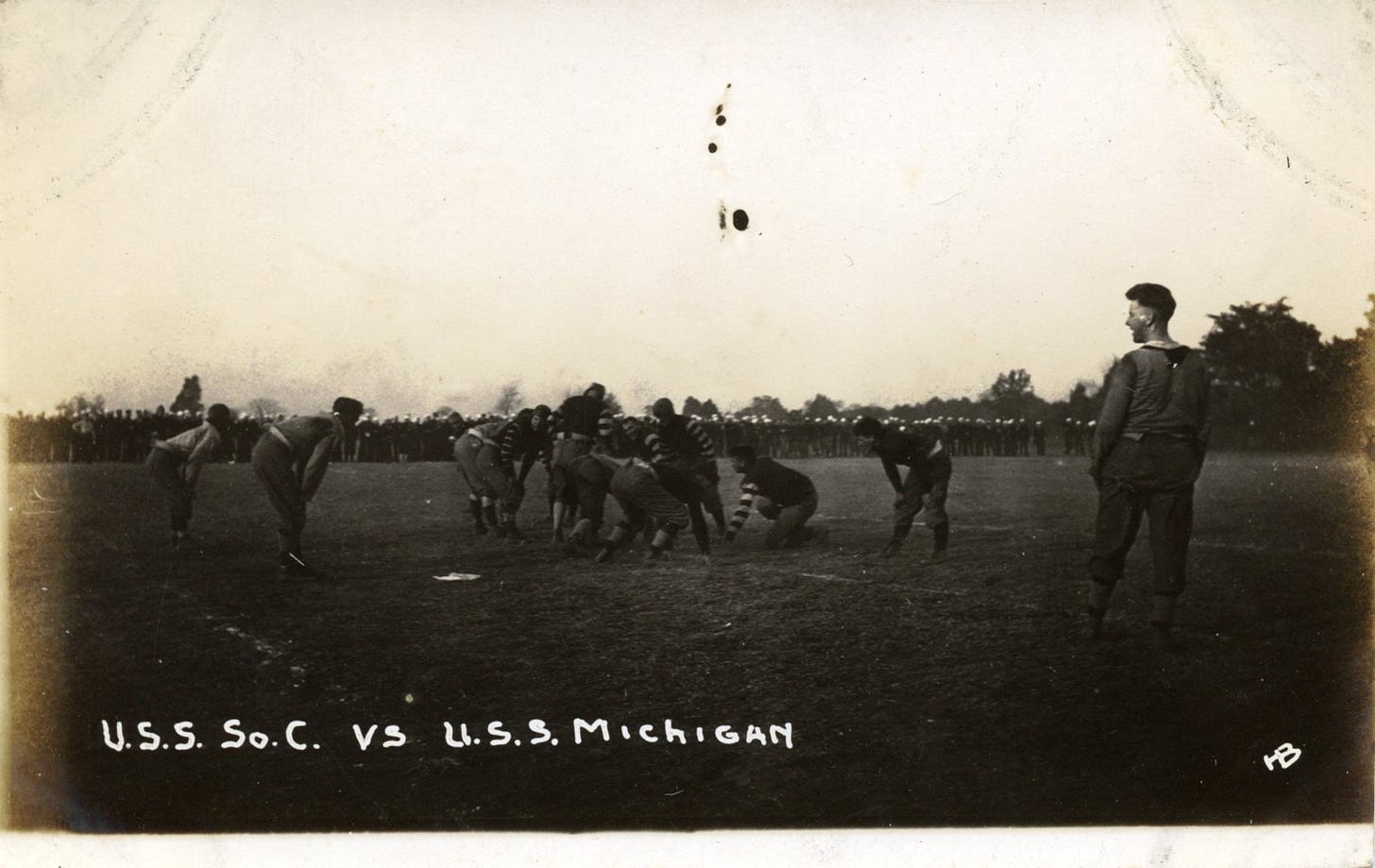

Other RPPCs show them in action against the USS Michigan, also based in Philadelphia, and another shows them facing the USS Connecticut, whose home was in Virginia. In all likelihood, one or the other was on maneuvers, and they scheduled a game while in the other team's port.

The only newspaper report found of a USS South Carolina game that year involved a mid-November contest at the Brooklyn Navy Yard against the USS Arkansas. It turns out that the South Carolina won the Philadelphia Navy Yard title and the Arkansas took the title for Brooklyn, so the teams met in the playoffs in Brooklyn, a game which the South Carolina won.

The South Carolina victory came at the hand, or rather, the toe of Ensign Harvey "Swede" Overesch. Overesch was the Naval Academy's football captain in 1914 and a three-sport letterman, so he faced Omar Bradley, Robert Neyland, and others when they played for Army.

Although he played end at Navy, he was the coach and quarterback of his battleship team. When the playoff game with the Arkansas ended in a tie, the teams played an extra period to determine which team was best, after which they likely would have flipped a coin to determine who went to the fleet championship game.

It looked like they might need the coin flip until the South Carolina boys reached the Arkansas 35-yard line with less than a minute to go. Overesch took the snap, and his dropkicked field goal attempt sailed true, giving his team the 9-6 victory and a date the following week with the USS Utah. The Utah, which won the playoffs for the ports along the southern seaboard, beat the South Carolina the next week to claim the fleet championship.

Four months later, the U.S. entered WWII, so Navy officers like Overesch had other things to do besides playing football. He served on the South Carolina throughout WWI, and then held a slew of roles on land and sea, taking more significant commands over time. He was a U.S. Naval attache in Shanghai when the Japanese attacked in 1937, became Commandant of the Naval Academy a few years later, and commanded the USS San Francisco, a heavy cruiser, in the Pacific in 1944 and 1945. After retiring as a Vice Admiral in 1946, he held leadership roles with the CIA in Asia and Europe.

Post-WWII, the military increasingly shifted to touch or flag football due to injury concerns. While some all-star tackle football teams continued until the early 1960s, they disappeared after that.

Notice: FootballArchaeology is not subject to Trump’s idiotic tariffs, so the $50 annual subscription is still just $50.

Click Support Football Archaeology for options to support this site beyond a free subscription.