Televising the 1945 Army-Navy Game

The war ended three months before, shortly before the football season began, and the country was starting to return to its civilian footing. Companies that produced armaments were returning to consumer products. Likewise, new products put on the shelf for the duration of the war were back in development. Others thought about how to apply the war's many scientific and technological advances to the civilian market. All these influences mashed together in a story of innovation that helped make football the game it is today.

Football has evolved tremendously in the last sixty-plus years. Much of that evolution is due to television and the money it poured into the game. Only the welcoming of African American players into mainstream football is comparable in influence, and two explain most changes in football since the 1940s.

For television to exert its influence, however, it had to take baby steps, one of which came with the telecast of the 1945 Army-Navy game. Commercial television barely got underway before the war. Boxing was the leading television sport, mainly because it occurred on small rings or stages, easily captured with a single camera. The first televised football game came when a New York City station broadcast the Fordham-Waynesburg game in 1939. A local station in Philadelphia carried Penn's home games from 1940 through the war. Still, like all other broadcasts of the time, it was available only within the broadcast signal of the Philadelphia station.

Before 1945, all television was local because the available technologies could not transfer video and audio signals from one city to the next in real-time. As a result, each televised show, including football games, could only be broadcast by a station near the stadium and was seen only on televisions within the local station's signal range. But that was about to change.

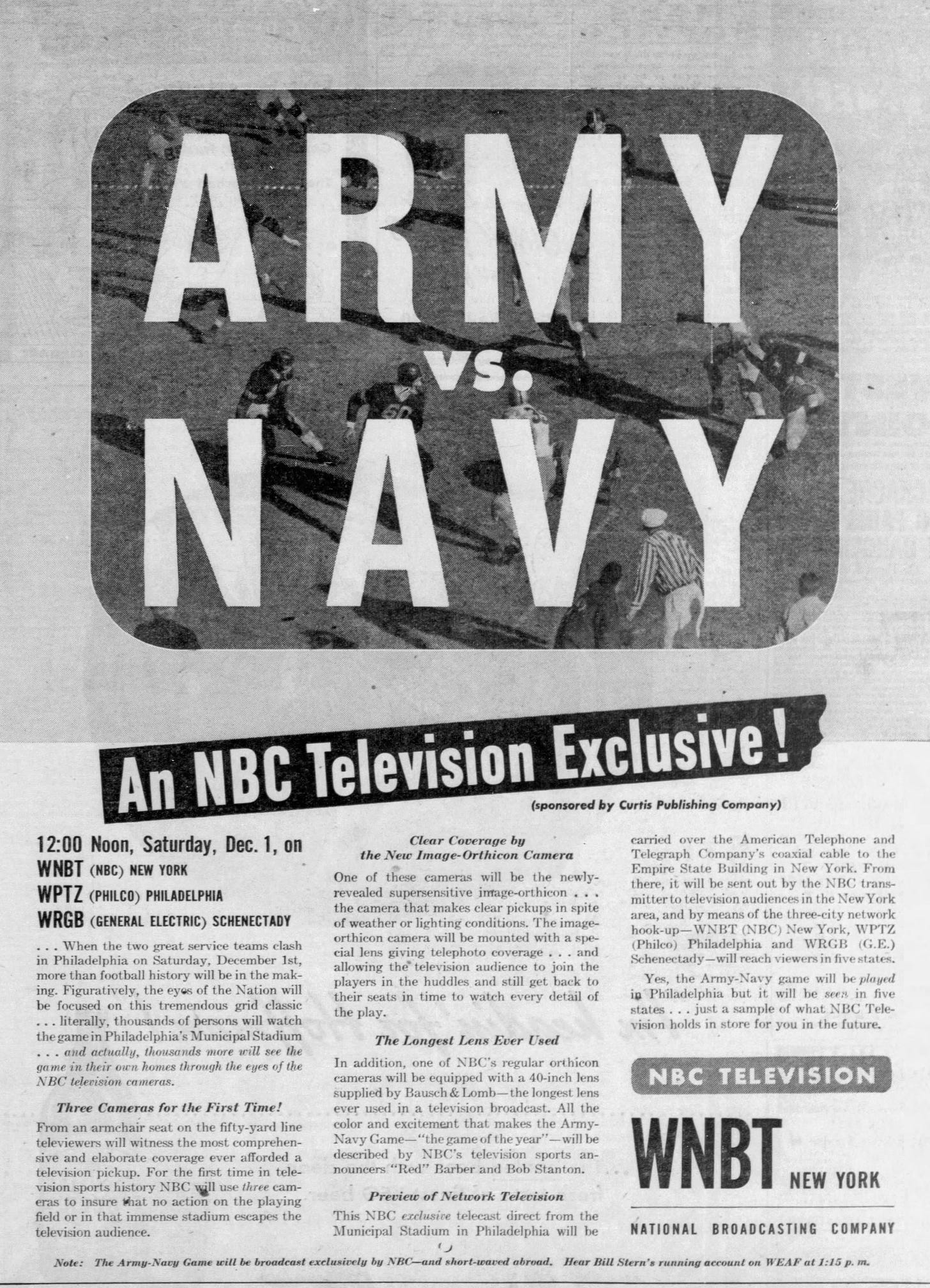

In mid-November, NBC announced they would televise the Army-Navy game played in Philadelphia on December 1. In the first test of a system to send live programming from one city to the next, the game would be broadcast in Philadelphia as usual and in New York City and Schenectady, both being connected via coaxial cables in recent weeks. WNBT, New York City's station, would accept the signal and beam it from atop the Empire State Building.

NBC used three cameras for the game, a football first. A camera atop the roof had the largest lens ever used on a television camera, while two others stood along the field at the 20-yard lines. Red Barber and Bob Stanton announced the action.

Watching a game played in a different city was a big deal in November 1945, and NBC promoted the game with newspaper ads and stories in the newspapers. WNBT also sent postcards to the audience of television owners and, perhaps, a few other influencers.

A problem for NBC was that the country had only nine television stations, and each had limited content since they could only show local live events. That meant the television audience was small, with an estimated audience of several thousand viewers able to watch the game at home.

Given the limited home audience, NBC hosted an influencer event at their Rockefeller Center studios to get the word out about their innovative broadcast. With 150 media and other guests attending, NBC had ten televisions scattered around the party, each showing the game on a 12 x 18-inch screen.

The reaction of the studio viewers was positive as the guests envisioned watching a game from home in the future. No cold air, wind, or rain to bother them while sitting in their favorite chair. Technically, the signal faded a few times, and the resolution was said to resemble an old newsreel. Still, the cameraman being faked out and not following the ball was the biggest concern expressed by guests.

No one attending the party at Rockefeller Center could have anticipated what television might look like fifteen, forty, or now, seventy-seven years later or the extent to which football and television would marry one another. Looking back, it all seems obvious, but a futurist that year did not anticipate televisions in every home. He saw the technology enabling pay-per-view events shown in movie theaters:

Madison Square Garden would become merely a studio in which to provide a ring, some lights, and a few thousand witnesses to boxing matches. Millions of fight fans in theaters around the country would make up the Garden's real audience -not the favored few in the $27.50 ringside seats. The same goes for the Kentucky Derby, the World Series and all the rest.

Myers, Sgt. Georg N. ‘American T.V. Broadcasting in the Mid-Forties,' Yank, January 1945

So, the Army-Navy game was a proof of concept that foretold the coming of live events to television stations nationwide. Of course, the market and the future would decide whether fans would see games in their homes or theaters, but television and football took an essential step by showing that 1945 Army-Navy game.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.