That Time the Team Captain Fired the Football Coach

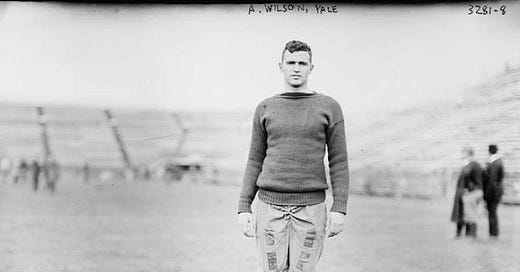

Top players in pro sports today influence coaching hires, but Alex Wilson played at the end of the era when college football team captains ran the show. And so it was that after Yale's loss to Colgate in 1914 with their record standing at 3-3, Yale's captain, Alex Wilson, did something unthinkable today. He fired the team's head coach.

To understand how that happened, we have to go back to the 1870s and 1880s when team captains ran college football. Coaches did not exist as we know them today. The team captain selected the team members and ran practices assisted by former players who popped in for a week or more, volunteering their coaching services to ol' Alma Mater. The returning alums actively participated in demonstrating techniques and scrimmaging, which is why colleges often played the first game of the season against alumni teams and many football coaches wore football gear during practice for decades to come.

As the nineteenth century turned to the twentieth, the captain as the supreme leader gave way to volunteer graduate coaches (those graduating from the same school) and professional coaches, but Yale was the last major school to implement that change. Yale's team captain, elected by the returning lettermen, continued running the show. After volunteer coach Walter Camp left Yale for Stanford in 1892, the Elis entered a twenty-some year stretch during which the previous year's captain or another recent Yale grad became head coach for a year. The head coach ran things on a day-to-day basis, but everyone understood he served at the convenience of the team captain. Most years, it worked out, and Yale, then among the largest colleges in the country, kicked everyone's butt.

After the 1914 season, the team elected Alex Wilson as captain for the 1915 season. It was a significant role given that Yale has influenced football's development more than any other school. It was often the best team in the country, winning eighteen national championships by that point and never having a losing season. The Yale Bowl opened in 1914 with a capacity three to ten times greater than any college not named Harvard or Princeton. Despite all that tradition, they lost to Virginia, Washington & Jefferson, and Colgate, and their record stood at 3-3 with games remaining with Brown, Princeton, and Harvard.

How did the season reach that point? Injuries felled five expected contributors before the season; others were lost to early-season injuries. That volume of injuries was catastrophic in the days of limited substitution since starters played both ways. Losing a starter had double the impact as today, even more, if they kicked or punted as well. But Yale's problems ran deeper by clinging to traditions that did not keep up with the times. They were the last major program to hire a paid coach when they brought in Yale alum Howard Jones in 1913. The 1914 team captain replaced him with Frank Hinkey, a quiet but ferocious four-time All-America at Yale whose teams in the early 1890s shut out forty-eight of the fifty-three teams they faced.

After his playing days ended, "Silent Frank" regularly returned to work with linemen as a volunteer assistant. Upon being named head coach, Hinkey visited Canada desiring to adapt the Northerners' open, lateral-heavy game to replace Yale's power offense. Things went well enough on paper in 1914 as Wilson, the quarterback, directed a stagnant offense and team to a 7-2 record. However, the season ended with a 36-0 loss to Harvard, the worst in Yale's history. It did not sit well with those close to the program.

The inability to move the ball also marked the 1915 season as Yale scored only seven points in their three losses, and one of their wins was a 7-6 victory over Lehigh. With Princeton and Harvard looming, Wilson made his decision. He fired his head coach, replacing him with Tom Shevlin, another Yale All America with a larger-than-life personality who was a decade younger than Hinkey. Shevlin worked his magic in 1910 when he returned to Yale to help rescue the season, and Wilson hoped a repeat performance might be in the offing.

As he had in 1910, Shevlin immediately added the Minnesota Shift to the offense for their tilt with Brown. Perhaps the addition surprised Brown since Yale opened the game looking like a new team, immediately driving down the field and getting inside the 10-yard line before stalling. Unfortunately for Yale, that was the only time they moved the ball, and they ended the day with a 3-0 loss.

Now standing 3-4, Yale got back to work, focusing on fundamentals for their game at Princeton. Once again, Yale struggled to move the ball but capitalized on numerous Princeton errors to win a tight contest. Neutral observers considered Princeton the better team, but Yale won to even their record at 4-4. A rejuvenated Yale team returned to New Haven looking to battle the 7-1 Crimson in Cambridge the following Saturday. It looked to be a difficult task. Harvard, under Percy Haughton, was in the midst of its most successful period on the gridiron, having already claimed several national championships that decade. Still, Shevlin had another week to inspire his players and bring the best out of the team.

Perhaps the crowd at Harvard Stadium that day should have paid more attention when Harvard's captain, Eddie Mahan, met Alex Wilson at midfield for the pre-game coin toss. Under the rules of the time, the team winning the toss received the kick and selected the goal to defend. Mahan and Harvard won the toss, foreshadowing the rest of the day. Mahan had four touchdowns and dropkicked five extra points as Harvard destroyed Yale, 41-0, sending the blue team home to stew on its first losing season.

Shevlin soon returned home to Minneapolis and his lumber business, bringing with him a bad cold, which led to pneumonia and Shevlin's death in late December at age 32. Unfortunately for all, Shevlin's death was not the last tragedy tied to the 1915 Yale team.

Wilson graduated in the spring and returned to Binghamton, New York, to work in his father's grain and elevator business. He was settling in when America declared war in April 1917. Wilson quickly enlisted and entered officer training, earning a commission as a second lieutenant. Wilson's next stop was Camp Syracuse, where he helped organize and train the 47th Infantry. He played for the 47th Infantry football team in their games with Syracuse, Cornell, and the Canton Bulldogs, a game in which Jim Thorpe made an appearance.

Wilson shipped to France with the 4th Division in May 1918 and participated in the Aisne-Marne Offensive and the reduction of the St. Mihiel Salient. Wilson and the rest of the 4th Division then moved north and went over the top on September 26 as part of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, a battle that cost more than 26,000 doughboys their lives. Wilson's company was in reserve the first two days but moved forward on the third day, the same day Wilson was promoted to captain. On the morning of the 29th, Wilson suffered an arm wound but refused to retire from the field. While advancing with his men that afternoon, a second bullet struck Wilson, killing him instantly. He is buried nearby with 14,000 others in the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery.

Frank Hinkey also left Yale after the 1915 season and never again assisted with its football team. Instead, he returned to the tin smelting business where he'd spent most of his career, but he fell into ill health in the early 1920s, succumbing to tuberculosis in 1925.

After Shevlin's departure, Yale hired Tad Jones as the coach for the 1916 season. He coached Yale for ten of the next eleven years, winning eighty percent of his games. Tad Jones was another in the long line of Yale coaches who were Yale alums, a streak that continued until WWII. Jones also started a new streak that continues today of Yale coaches who were not fired by the team captain.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.