The Art of Football Officials' Signals

This story appeared in Sunday’s edition of Uni Watch under the same title.

Some innovations in football arise from the game's rule-makers, others from coaches looking for an edge, and still others from the R&D departments at sporting goods manufacturers. But another group of innovations comes from individuals who see a need and create a solution to address it. That was the case with the contortions officials perform when signaling their rulings on the field, particularly the penalties being enforced.

When football stadiums began growing at the start of the 20th century, they were information deserts. Players did not wear numbers, scoreboards gave the score and little else, the chain crew did not display the down number, and loudspeakers did not yet exist, so fans and the press had difficulty tracking the events on the field. Newspaper reports often credited the wrong player for a touchdown run or touchdown-saving tackle. Only through post-game interviews did the press learn which penalty was called in a crucial situation.

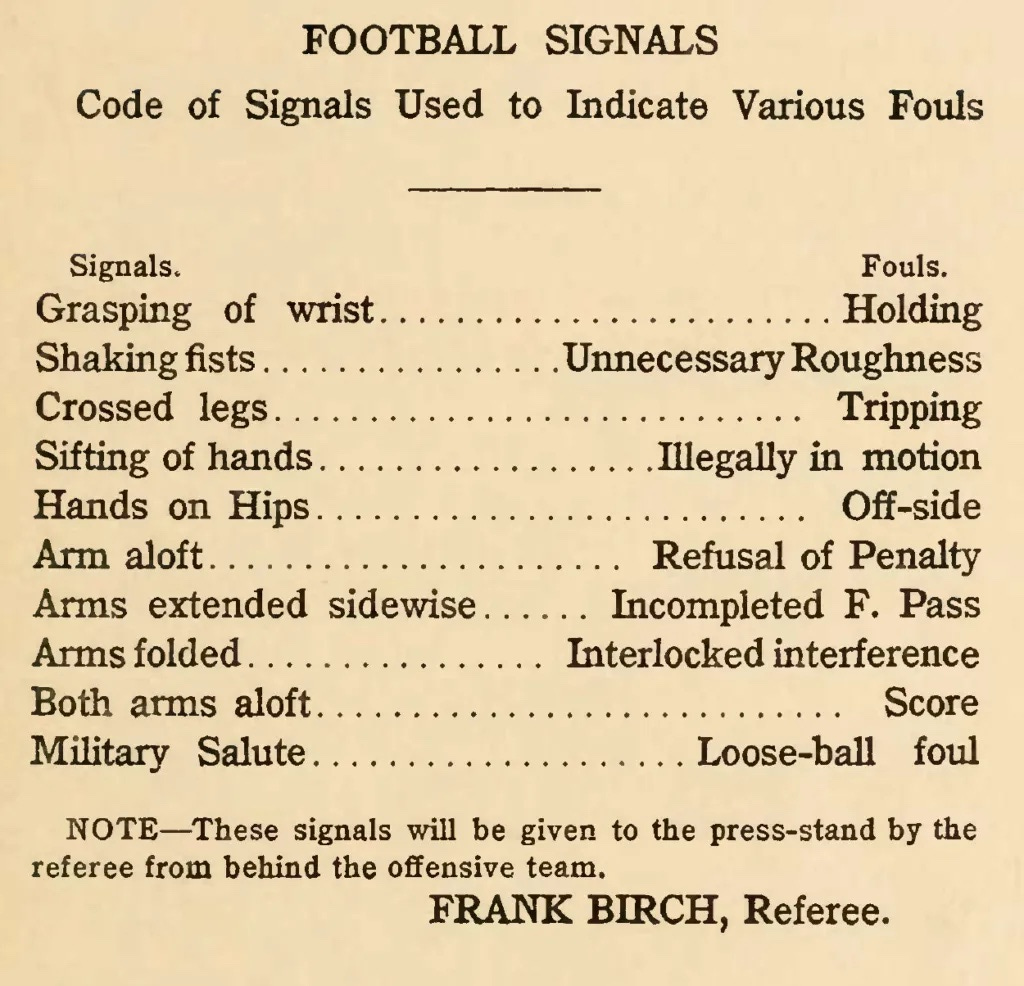

A solution to the last problem began to emerge around 1910 when Frank Birch, a football official living in Iowa and then Illinois, developed a system of hand and body signals that matched those on cards he gave to members of the press before the game. Birch performed his signal routine whenever he marched off penalties while also using signals for touchdowns, incomplete passes, and the like.

Some of Birch's signals changed over time, and others went away due to rule changes, but several on his early list remain in use today.

Since Birch officiated Big Ten and other major conference games, word of his innovation spread, leading to major officiating organizations adopting a version of those signals in 1929. Games being reported live by radio reinforced the need for the press to have real-time information on penalty calls.

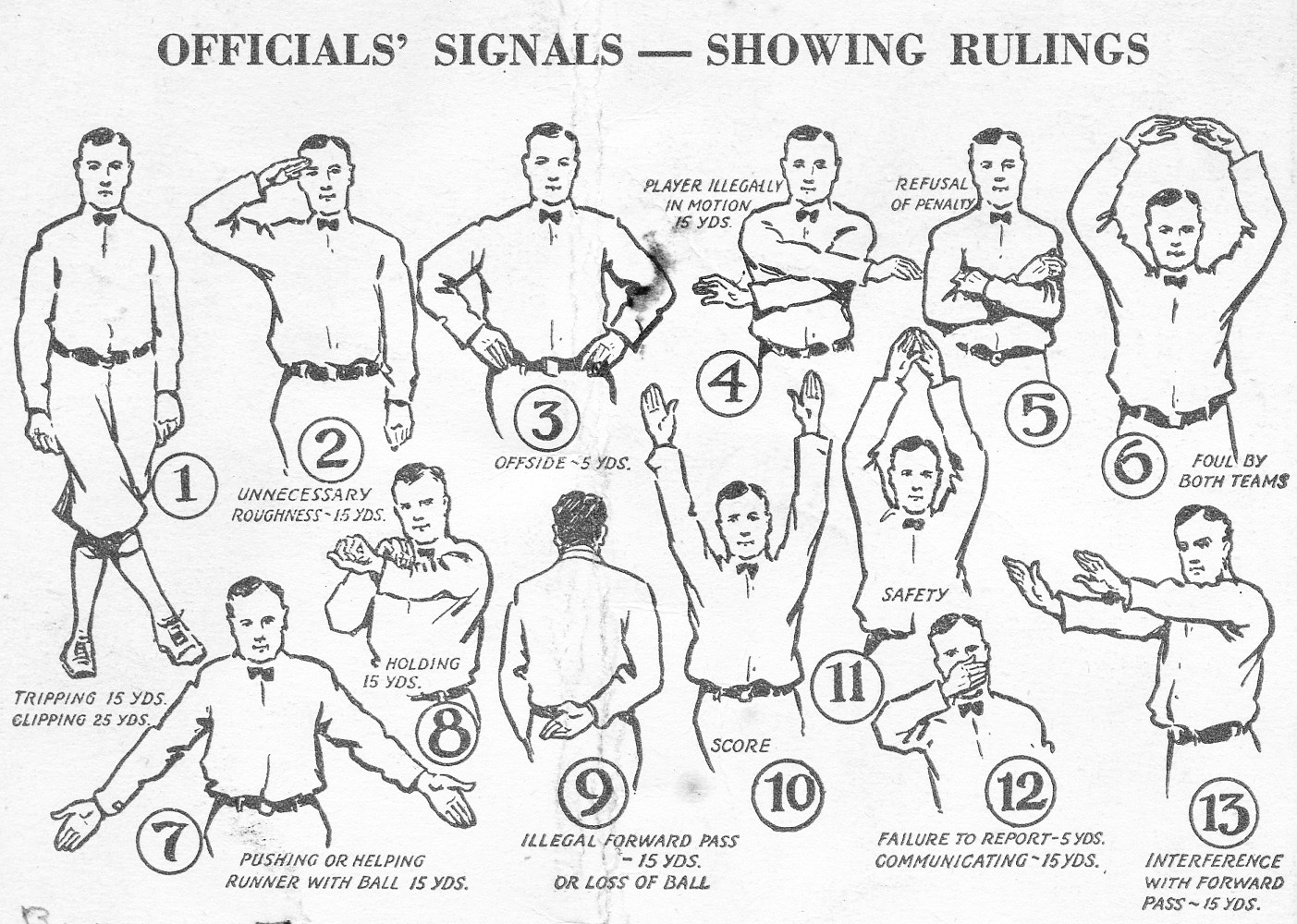

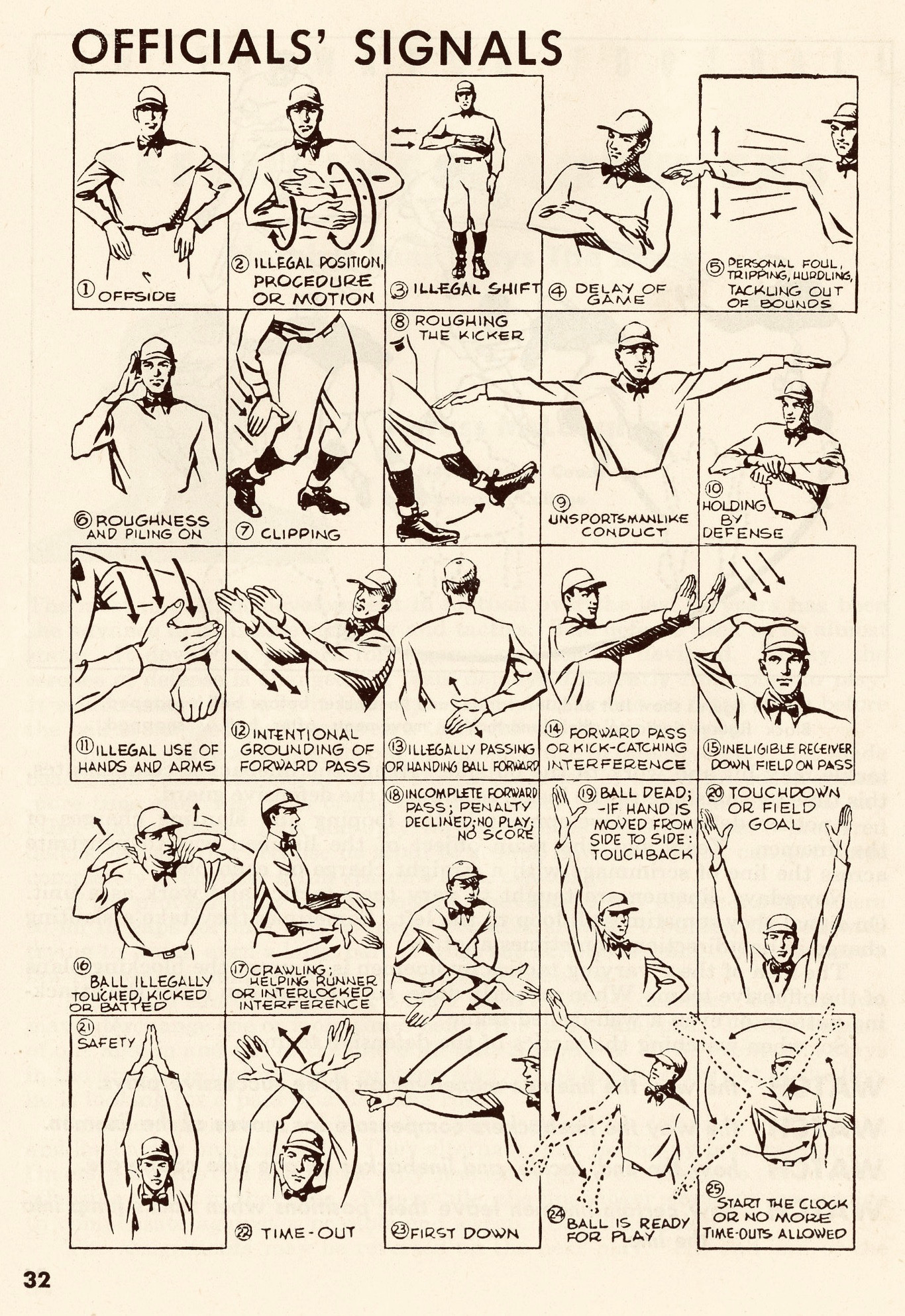

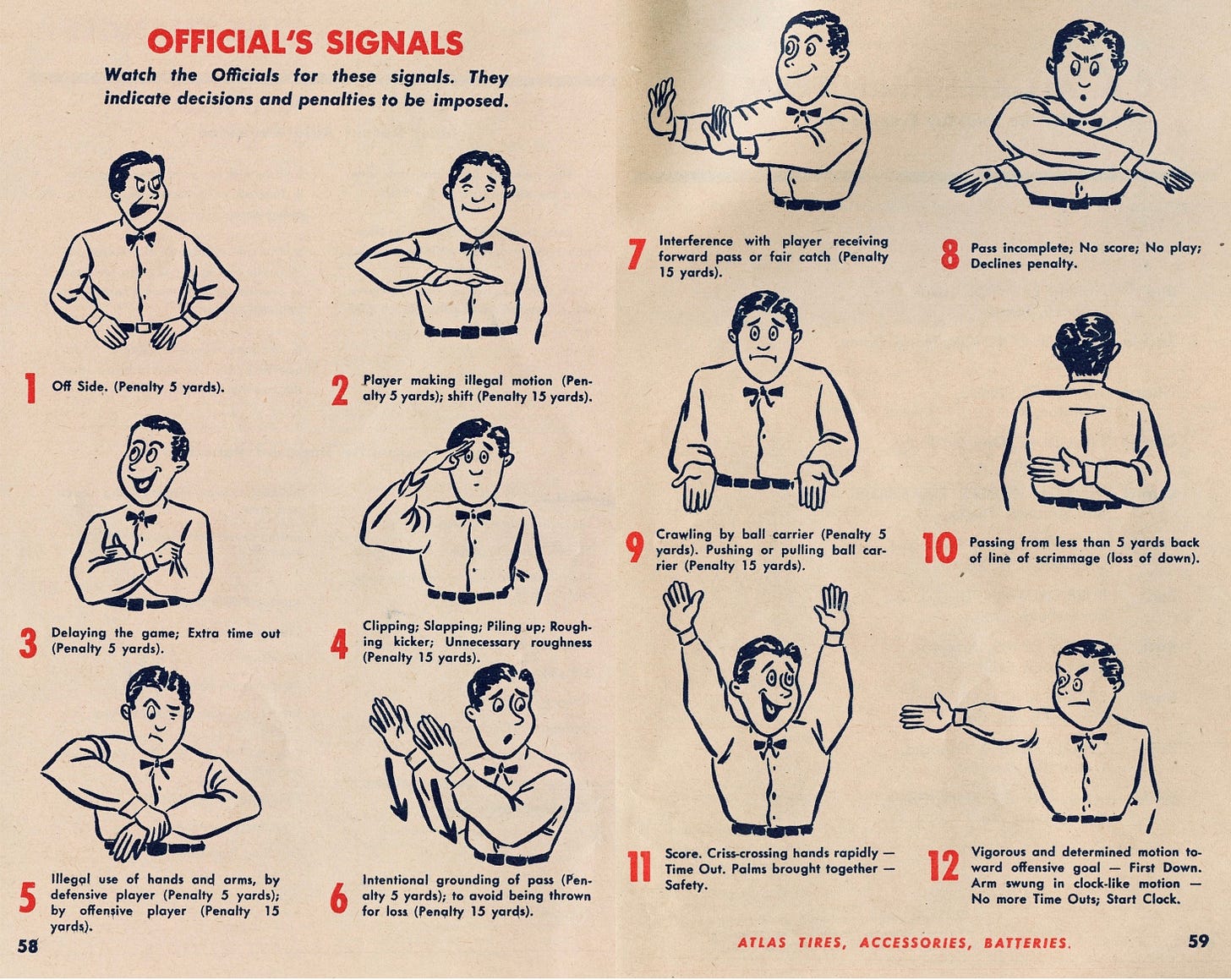

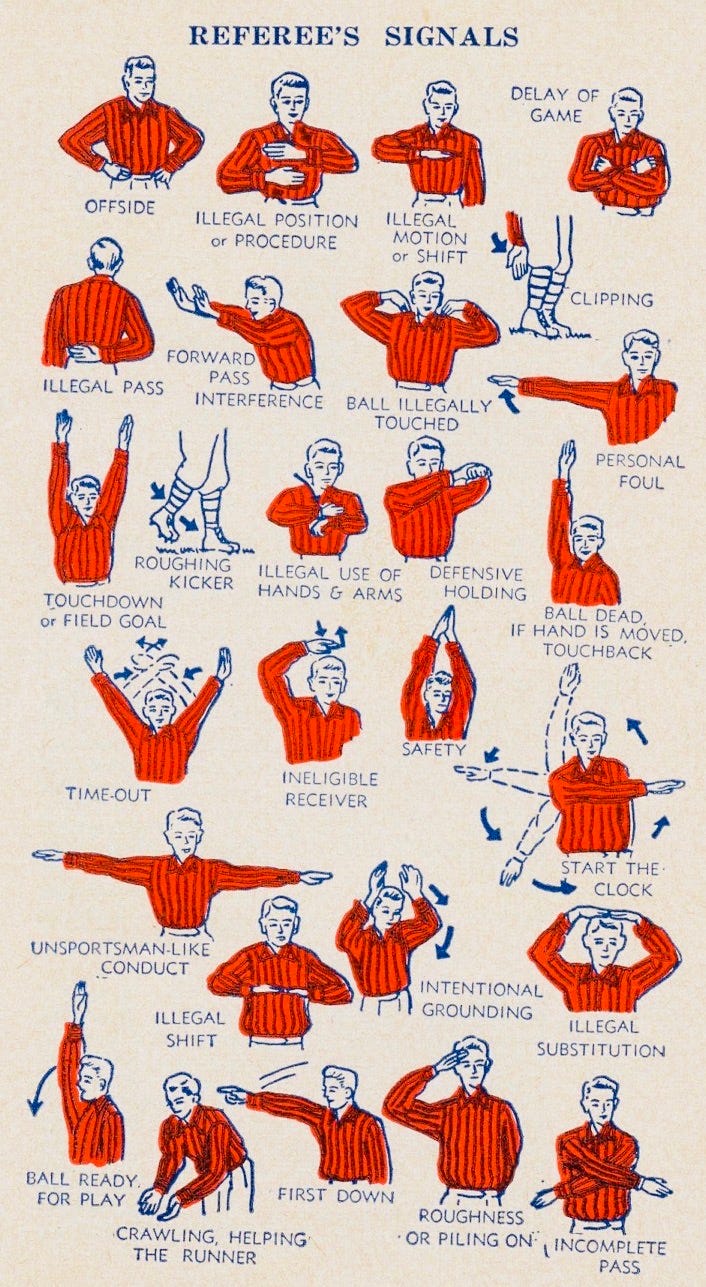

As the referee's signals became more popular, game programs and other football publications described the signals so fans could better track the on-field happenings. Rather than describe the signals, they often included two-dimensional illustrations to convey the officials' motions. Most worked well; some motions proved difficult to convey.

Among the best at conveying the officials' motions were the illustrations in a 1953 Oldsmobile brochure highlighting the brand’s sponsorship of weekly college football telecasts.

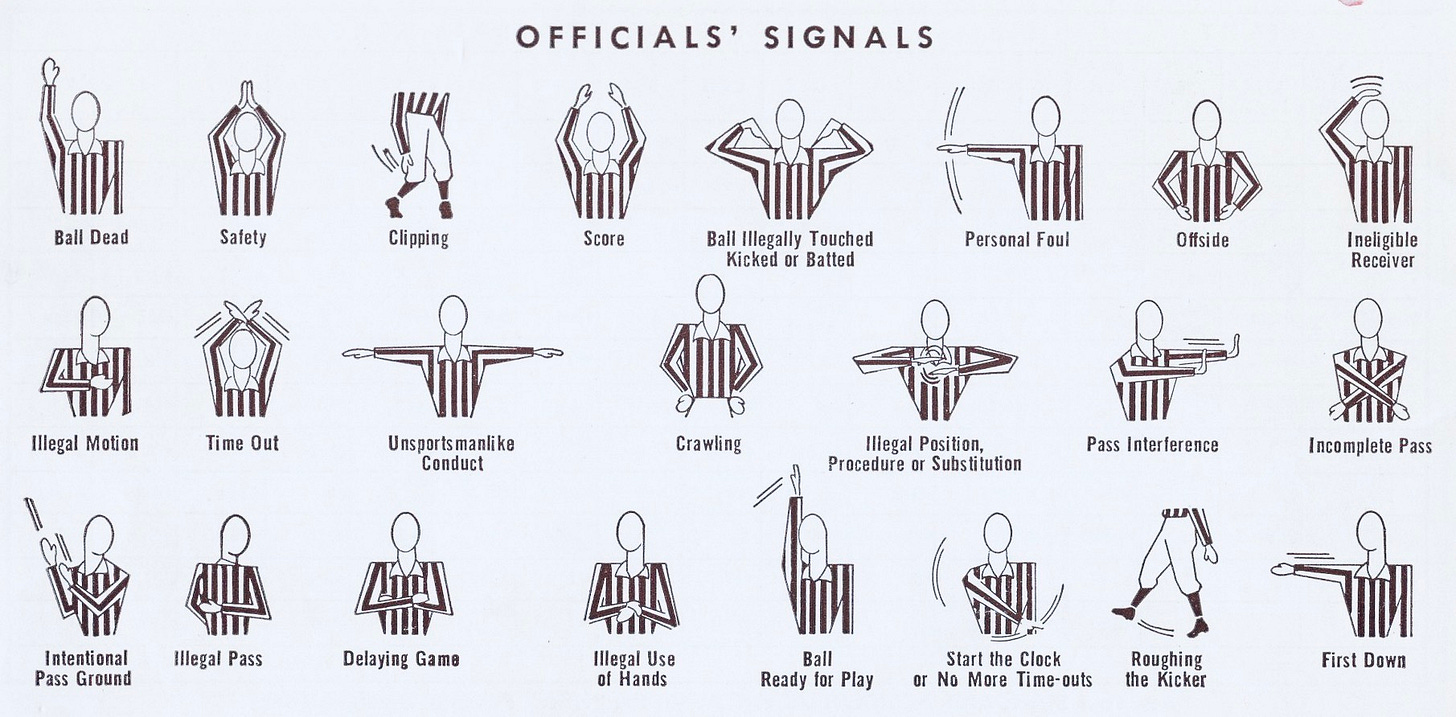

Another approach came in a 1959 brochure from an insurance company that caught the minimalist bug, turning the poor officials into faceless creatures.

The opposite approach show officials as humans subject to surprise, joy, or error.

A few added a splash of color, though most cried fouls when they saw the official's zebra shirt dyed in a color that did not exist in the wild.

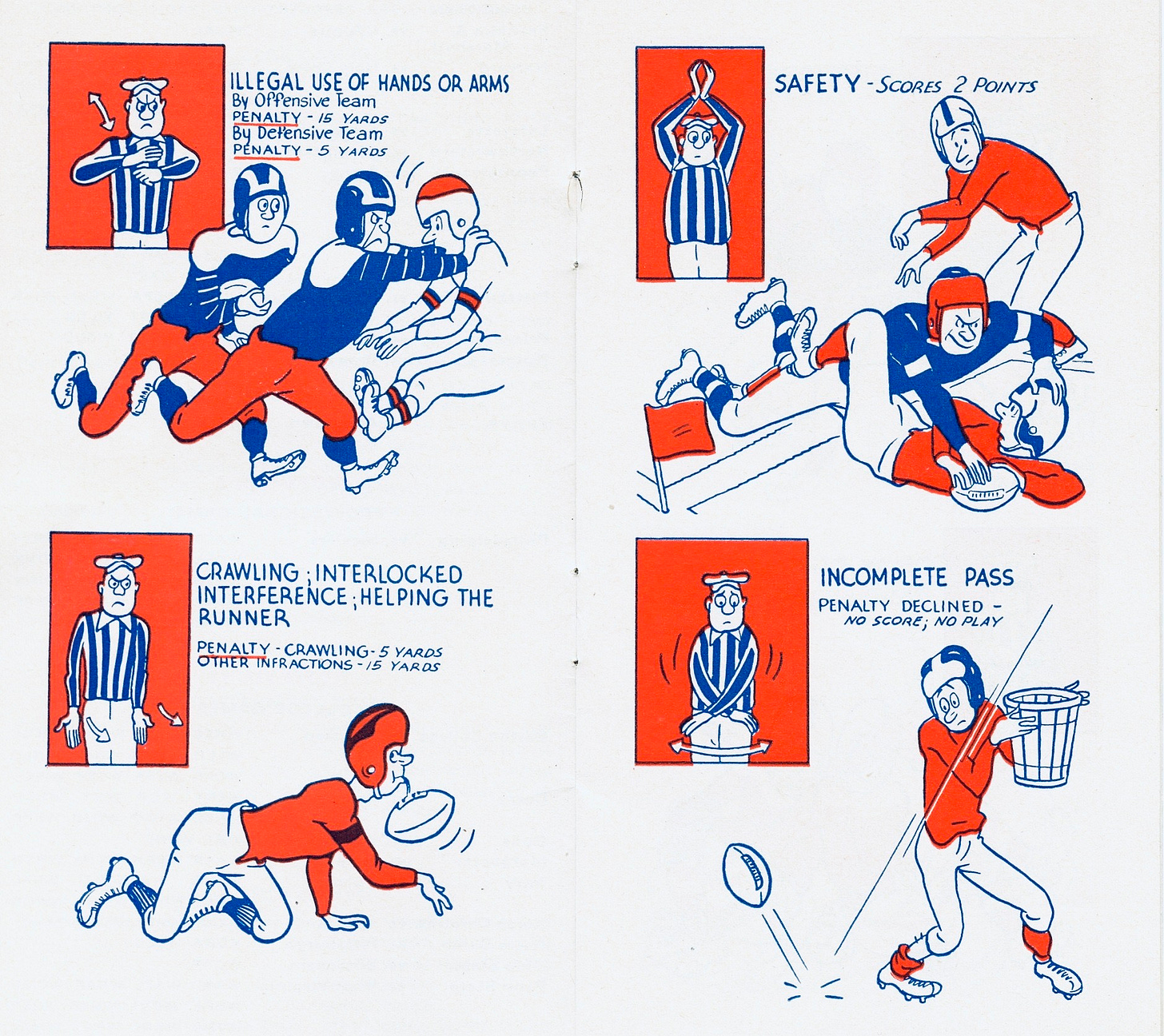

However, none of the examples above approach the masterpiece produced by Bo Brown for a 1950 Atlantic Oil service station brochure. The five pages of illustrations may not have been as clear as others in illustrating the officials’ signals themselves, but the drawings of the infractions are worth any information loss.

Although football and parts of society have advanced since the 1950s, the officials’ signals have seen little change. They nailed most of them the first time around and demands to change the signals have been few, though there was one time folks cried foul. The signal for unnecessary roughness was a military salute until 1955. At that point, when the American Legion complained that schoolchildren confused the penalty signal with the act of saluting the flag. So, the signal on the field was overruled, and the game adopted new signals for different categories of personal fouls.

Football has added and refined its penalties since the 1950s, and fans have more signals to learn than in the past. However, the NCAA’s official signal illustrations in the 2022 rule book look much like those from 1932, so we have not moved the needle on our penalty signal illustrations, and perhaps we never will.

Click here for options on how to support this site beyond a free subscription.