The Bliss Brothers, the Reverse, and the Flying Wedge

Here's a story about a pair of brothers who were on the football field when teams executed two of football's best-known plays for the first time. They were on offense the first time and defense the second. Notably, neither play resulted from a rule change. Instead, the new plays resulted from the inventiveness of the team's coaches or team members.

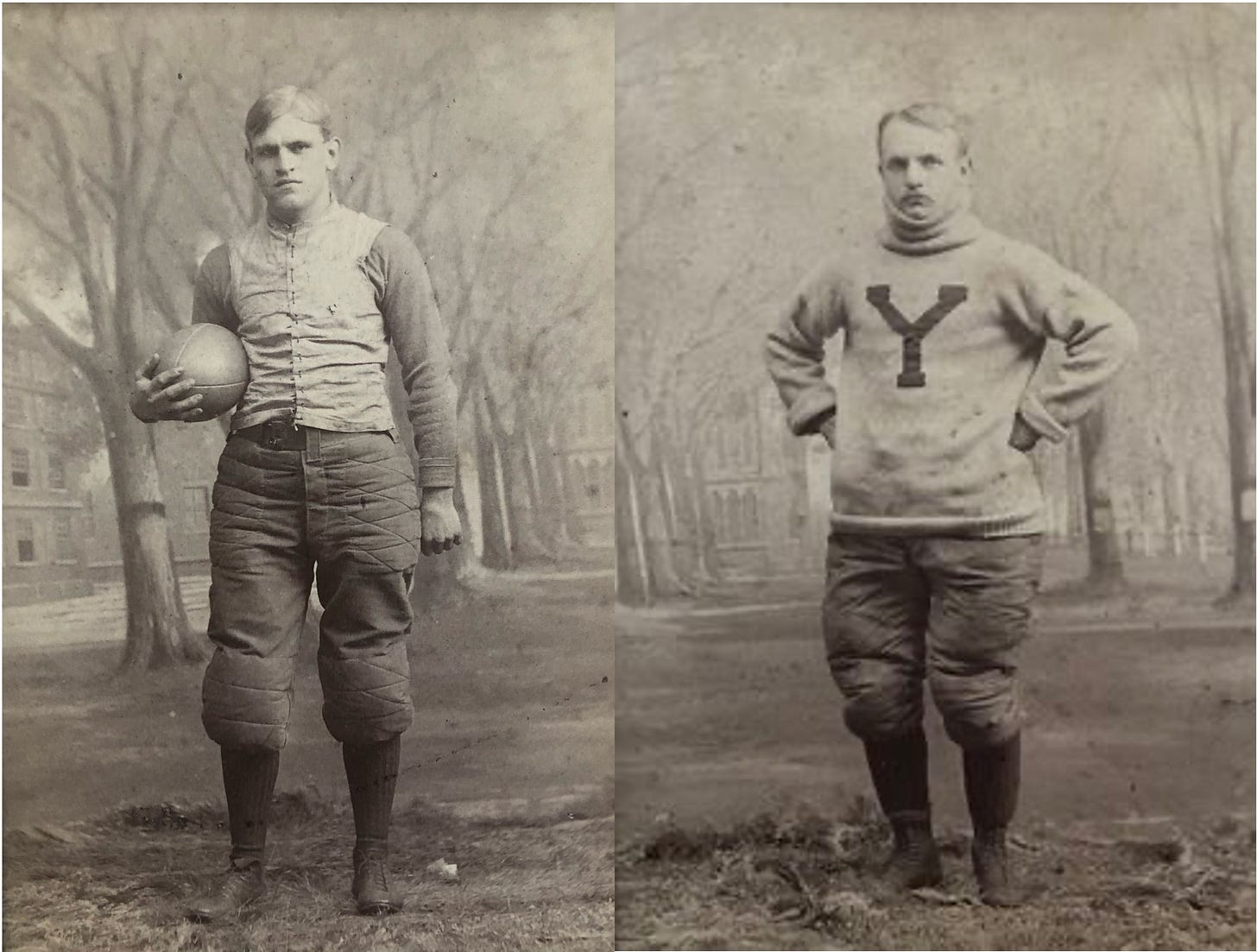

The Bliss brothers, Laurie and Pop (C. D.), played together for Yale in 1891 and 1892, when the Bulldogs won 26 games in a row, two IFA championships, and were retroactively named college national champions. Yale didn't have much competition then, but with Walter Camp as their coach, they were the best of the time and were in the middle of the game's development.

Before the Bliss brothers enrolled at Yale, they attended Phillips Andover, an uber-elite prep school. Andover's resources put them ahead of most teams from a coaching, technique, and strategy standpoint, allowing them to play and beat top prep schools, college freshmen teams, and less competitive college varsities.

The Bliss brothers were backfield mates when Andover played rival Exeter in 1888. Someone at Exeter had the idea for a new play, which they saved for their season-ending game with Andover. The play was the first designed to use misdirection. It saw Exeter quarterback Lou Owsley take the snap and give it to Laurie Bliss as Laurie started running around the end. However, before Laurie got far, he gave the ball to his brother, Pop, who was running in the other direction. News reports of the time described the trick play as a first-timer, and it became known as the criss-cross or cross-buck. That means the Blisses were part of the first criss-cross, crossbuck, counter, reverse, or any other misdirection play, with three players handing the ball.

Four years later, the Blisses were on the field for the 1892 Harvard game. Someone at Harvard (Lorin Deland) had the idea for a new play, which they saved for their season-ending game with Yale. Harvard had run wedge plays from scrimmage in the first half and wanted to surprise Yale when they kicked off to start the second half with the score tied 0-0.

In 1892, the team kicking off retained possession of the ball since the rules did not require teams to kick the ball ten yards. Like soccer, teams dribbled the ball to a teammate or the kicker picked it up and ran with it or tossed it to a teammate. Rather than follow that approach, Harvard executed its Flying Wedge, in which two groups of five players aligned behind and to either side of the kicker. On signal, they ran toward the kicker, who dribbled the ball, picked it up, and gave it to a teammate who ran behind the wedge running full speed toward Yale. Thankfully for Yale, the Harvard runner tripped and fell after a dozen yards, so Harvard never threatened to score. (Due to the danger posed by the Flying Wedge, the 1894 rule makers effectively banned the play by requiring the ball to travel at least 10 yards on a kickoff.)

The game remained scoreless until there were 12 minutes left when Yale drove from midfield and was inside Harvard's 5-yard line. With the ball on the right side of the field, Yale gave it to Laurie Bliss, who headed into the wedge formed by his teammates as they drove into Harvard's line. However, Bliss suddenly popped from the pile and sprinted around the left end for the game's only touchdown, allowing Yale to win 6-0.

Both Blisses graduated from Yale in 1893. Laurie coached Army in 1893 and Lehigh in 1895 before entering a business career. Pop coached Stanford in 1893, Haverford in 1894, and Missouri in 1895 before also pursuing a business career.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.

This story was pure Gridiron Bliss!