The Emergence of Football's Game Stats

Changes in college football make it difficult to compare players across eras. For example, quarterbacks playing in today's pass-happy, two-platoon game face demands and generate vastly different statistics than those who played in the run-oriented, single platoon college offenses of the 1950s. The 1950s quarterbacks are also difficult to compare to the pre-1940s quarterbacks whose main jobs were to block for the triple-threat halfbacks and fullbacks.

As difficult as it is to compare players across eras, it was once difficult to compare those playing the same year due to the lack of game and summary statistics. Before the late 1930s, teams and newspapers tracked information about their games. Still, each did so idiosyncratically, tracking different game elements without a central clearinghouse to summarize and publish stats to compare one player against another.

The lack of centralized stats reporting reflected a game organized at the conference or regional level. The most significant national reporting before 1905 came in tracking the deaths due to football or the summary reports published by Camp and others that tracked plays (e.g., the twenty players with the longest runs or punts per year) or the players scoring the most touchdowns and field goals in a season. Similarly, no one knew how many players ran for 100 yards in a game or 1,000 yards in a season because no one tracked that information or did so in a regulated manner.

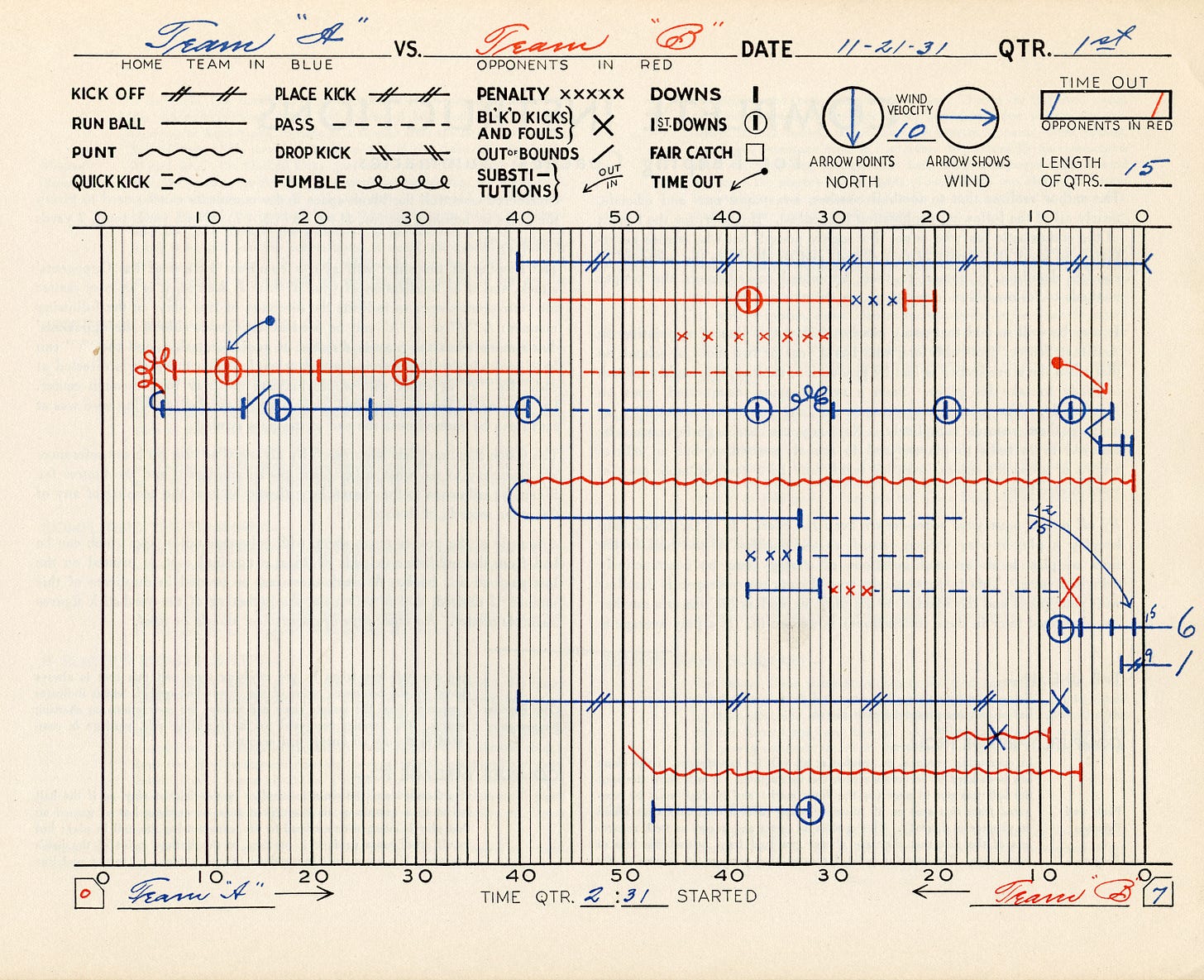

The lack of statistics did not reflect a failure to track game events. Reporters and others tracked every run, pass, kick, fumble, and penalty using forms such as the one below.

The information from the raw game charts led to published drive charts such as the following for the 1904 Cal-Stanford game, which even tells the reader the hole through which each run occurred. Although the chart comes from a yearbook, it is consistent with the newspaper reports of the game, as is the yearbook's multi-page report on the game events.

Despite people across the country charting games in detail, nowhere could readers find summary statistics. Newspapers seldom told readers how many times the star halfback ran the ball or how many yards he gained, though that information was readily available from the raw drive chart.

Here and there, folks began cumulating this information on a team-by-team basis. Consider the year-end statistics reported in the 1911 Kansas State Royal Purple yearbook. Their summary information took significant work, but their methods and assumptions differ from game statistics today. The paragraph preceding the table tells us the scorekeepers credited pass catchers with net yards gained, as they did rushers. However, punt returners were not credited with a return attempt when tackled immediately. Their decision to credit yardage to those recovering punts makes sense since the rules allowed offensive players to recover and advance punts via the onside kick from scrimmage. (Legal between 1906 and 1911, somewhat different rules preceded and followed the onside kicks of 1906-1911.)

The statistics show that Kansas State gained an average of 795 yards per game, including 1,152 yards in a 57-0 victory over William Jewell and 1,169 yards in their 75-5 beatdown of Drury. Topping 1,000 yards in a game is difficult, even against inferior opponents, so they likely included punts in their total yardage calculation. On the other hand, William Jewell gained 47 yards in 12 attempts, which seems odd even if they punted on first down each possession. Perhaps the game statistics included only plays gaining positive yards, but however they performed their calculations, their methods differed from ours.

Two decades later, Virginia's Corks and Curls yearbook published the Cavaliers' 1922 season statistics. The statistics included the yards gained on line and end plays, which is likely the same at total rushing yards. Virginia's report resembles that of today but retains the period focus on punting yards and it is unclear how they calculated their statistics.

The emergence of modern football stats needed three steps to reach a form similar to today. First, each game needed an official scorer to distribute the game info to press members, so everyone sang from the same songbook. Consider Red Grange's performance against Michigan in 1925. The Chicago Tribune reported Grange ran for 262 yards on his first four touches: a 95-yard kickoff return, a 67-yard run, a 56-yard run, and a 44-yard run. The Associated Press reporter saw the events as a 99-yard kickoff return, a 65-yard run, a 55-yard run, and a 45-yard run. Four touches by the game's greatest player in the biggest game of his career, reported by two top press outlets of the day, yet none of the four yardage figures match. That needed fixing.

Second, consistent statistics required the development of consistent counting rules.

Do we count the yardage on punts and field goals from the spot of the kick or the line of scrimmage?

Should we distinguish yardage on pass plays before and after the catch? What of passes caught behind the line of scrimmage?

Should yardage lost by quarterbacks count against their rushing or passing yardage?

Do first downs that result from a penalty count as first downs? Should teams receive credit for one or more first downs on a long touchdown run?

The game needed answers to those and other questions with rules developed to ensure consistency across time and space.

Third, assuming everyone could agree on the official scorer and counting rules, football needed someone to gather and summarize this information, and that is where Homer F. Cooke, Jr. entered the picture. In doing so, Cooke made what is likely the most significant contribution to football that came from its semi-pro ranks. Gamblers, fantasy football owners, and every other fan are in Homer's debt for having popularized a standard process for football statistics that remains the system used today.

Cooke was a sportswriter for several newspapers and part-owner of a semi-pro football team in the Northwest during the early 1930s when he convinced the semi-pro Northwest Football League to track game statistics using a system he developed. To gain agreement, Cooke offered to teach the counting rules, gather the information from each team, and summarize and share those statistics.

After working out the kinks in his league, Cooke asked various major college programs to use his system and report their statistics. Joseph H. Petritz, sports publicity director at Notre Dame and Fielding Yost, Michigan's former coach and a member of the NCAA Football Rules Committee, supported his efforts, arguing Cooke's case to their respective committees. Within several years, the home team's official scorer at all major colleges followed Cooke's rules and submitted their information. The Associated Press began using his summary numbers, and Cooke's American Football Statistical Bureau became the official source of NCAA football statistics. In 1959, the retiring Cooke sold his bureau to the NCAA, which absorbed it, with the result that the NCAA's official statistical records for football begin with those gathered by Homer Cooke, Jr. in 1937.

Football now tracks all types of statistics -including those for defenses and defensive players- and technology eases the burden of doing so. However, despite substantially better statistics, it remains difficult to compare players from the same year -look no further than early-round NFL draft busts for confirmation- and comparisons across eras are ever more difficult as the game continues to evolve.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.