The End of an Era: Harvard’s 1920 Rose Bowl Win

The dinner hosted by the Harvard Club of Boston in February 1920 to honor Harvard's 1919 football team was not your run-of-the-mill dinner, but it had not been a run-of-the-mill football season. Playing during football's fiftieth anniversary season, the team had recently won the 1920 Rose Bowl – the only bowl game in Harvard's history – but it was more than that. It was the first football season since WWI ended when tens of thousands mustered out and returned to college, swelling the ranks and quality of the nation's football teams.

Percy Haughton, the Crimson's most successful coach, left Cambridge after the 1916 season to concentrate on business matters. Harvard fielded an informal team in 1917 and played only three games in 1918 when the nation's football schedules were ravaged by the Army nationalizing the nation's colleges and the Spanish Flu. The 1919 team played under first-year coach and former Harvard All America, Bob Fisher.

Harvard returned a backlog of talent, with every team member wearing a military uniform the previous fall. A few were on campus as Student Army Training Corps members, but the majority were on active duty with a number serving overseas, including team captain Bill Murray, who was an ensign on the U.S.S. San Diego in July 1918 when it struck a mine and sunk off Long Island, the only American capital ship sunk during WWI. In addition to the players, coaches Fisher, Mahan, and Parmenter also served.

The 1919 schedule was typical of the era, playing a handful of lesser teams in the early season and leaving its most challenging games for the season's end. Also typical was Harvard playing only one away game, facing Princeton in New Jersey. (Between 1900 and 1935, Harvard played at Princeton one year and Yale the next. They only played a second away game when Army or Navy appeared on the schedule.) Harvard rolled through their first six games, shutting out each opponent, before tying at Princeton. An easy win over Tufts and a 10-0 victory over Yale left them at 8-0-1 and the last undefeated Eastern team willing to accept a Rose Bowl invitation.

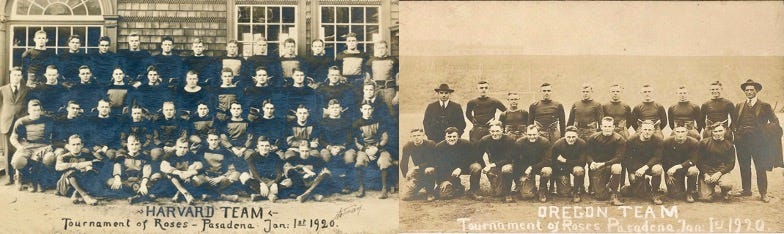

The Rose Bowl saw Brown meet Washington State in 1916, followed by Penn versus Oregon in 1917, while military teams played in the 1918 and 1919 Rose Bowls, so Harvard's matchup with Oregon in 1920 marked a return to normalcy.

The team left Boston on December 21 on a trip that remains the longest distance ever traveled by a Rose Bowl team. The six-day train ride included brief stops during which the team tried to keep in shape by exercising or running plays on the station platforms and nearby streets. A full workout on Christmas Day in San Francisco preceded the final leg of the journey to Pasadena, where the newspapers noted Harvard's ten pounds or greater advantage at most positions.

Oregon was no slouch, however, finishing the regular season at 5-1. They tied with Washington for the Northwest crown with their victory over the Huskies, giving them the Pasadena bid. Oregon also had experience with three players who started in Oregon's 1917 Rose Bowl win. All three also played on a military Rose Bowl team. Tackle Ken Bartlett played for Camp Lewis in 1918, running back Hollis Huntington was the 1918 Rose Bowl MVP for Mare Island, while Bill Steers started in Mare Island's 1919 loss to Great Lakes. Another starting lineman for Oregon, Ward McKinney, was a sub for Oregon's 1917 Rose Bowl team and Camp Lewis in the 1918 game. So, four Oregon starters had been there before. Twice.

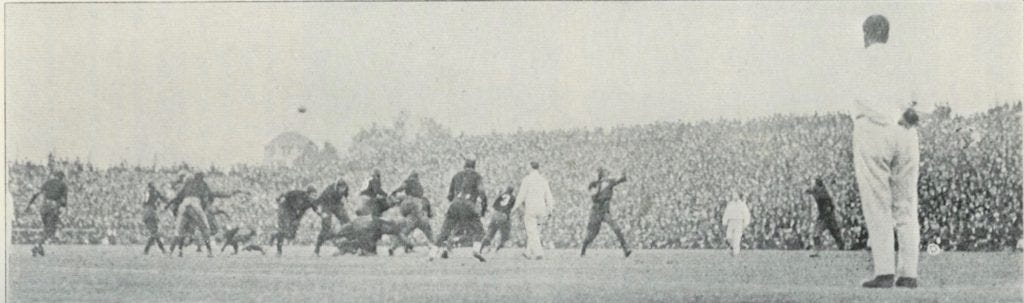

The game itself was low scoring, with Harvard's bigger line alternately pushing Oregon around and becoming fatigued. Oregon's QB, Steers, began the scoring with a forty-yard dropkick field goal before being knocked unconscious. Manerud, Steers' substitute, also converted in the second quarter, but Harvard earned a touchdown and extra point between Oregon's field goals. Oregon missed two field goal attempts in the second half, while Harvard failed to score from Oregon's two-yard line on the game's final play, giving Harvard a 7-6 victory. Hollywood stars Charlie Chaplin and Douglas Fairbanks congratulated the victors in the locker room after the game, and the team made the rounds of parties and dances before boarding the train home the next day.

After successive losses by Brown and Penn, Harvard's victory restored some of Eastern football's claim to supremacy, but the football gods had already shifted west and south. The Ivies' dominance in the 1880s and 1890s had given way to equality in the 1900s and 1910s. While they were among the nation's largest universities before WWI, the Ivies did not keep pace with state school enrollments or resources directed toward football following WWI. Perhaps the sense they would soon be left behind made the victory all the sweeter.

Arriving in Boston on January 7, several Harvard team members were feted in their hometowns. Still, nothing matched the Harvard Club of Boston dinner, held at the Copley Plaza Hotel, in meaning and elegance. (Now part of the Fairmount chain, it remains rather swanky today.)

The ballroom held 800 alums who settled in their seats to watch movies of the Yale game and Rose Bowl. Among the attendees were men who played for Harvard in the 1870s, whose experience playing McGill University ultimately led American football to take the rugby path rather than soccer, the sport most similar to that played by Princeton and Rutgers in football's supposed first game.

The first speaker was LeBaron Russell Briggs, the longtime Dean of Men at Harvard. During his tenure, Briggs ordered that Harvard's scoreboard show Harvard's score versus the "Visitor" rather than the "Opponent," a nicety that became commonplace on scoreboards nationwide. Briggs spoke of those who opposed Harvard's playing in the Rose Bowl compared to the positive impact of the game on Harvard's West Coast alumni and the university as a whole. Next up was Massachusetts's governor, Calvin 'Silent Cal' Coolidge, who said a few words. Four months later, Coolidge gained the Republican Vice-Presidential nomination as Warren Harding's running mate. Other speakers included the 1919 and 1920 team captains, former coach Percy Haughton, and the current head coach, Bob Fisher. Douglas Fairbanks, who appears in the program, did not speak. Neither did the Boston-area shoe salesman whose impersonation of Fairbanks left most attendees believing the real one had been there.

Interspersed among the speakers was the awarding of gold football charms to team members, singing of traditional Harvard songs, and a few ditties with lyrics written for the occasion. Among the latter was #14 Harvard Fight which borrowed its tune from Mademoiselle from Armentières, a song known to every doughboy and familiar today for its playing during the closing credits of They Shall Not Grow Old.

Despite the well-deserved celebration, Harvard's demise as a football power was underway. The team went 8-0-1 in 1920, earning its last national championship (as recognized decades later). As was the case before the war, Harvard returned to playing one away game in most years and did not play outside the East until traveling to Chicago in 1939, the year the Maroons dropped football. Three Harvard teams achieved rankings in the high teens of the Associated Press pool in the 1940s, while only a handful of Harvard players earned major college All-America status, with the last coming in 1932. The football world changed, and Harvard was unable or unwilling to keep pace. The formation of the Ivy League in 1954 put the official seal on Harvard's lack of competitiveness at the national level.

Click here for options on how to support this site beyond a free subscription.