The Evolution of Football’s Chains and Down Boxes

Although football's origin story tells us Rutgers and Princeton played the first football game in 1869, those teams and others played soccer, rugby, folk games, or a mix of the three through most of the 1870s. Football as a distinct game arrived only when teams began playing by rules that violated rugby's core principles. These included allowing interference (now called blocking) in 1879, the controlled scrimmage in 1880, and the 1882 requirement that teams gain five yards in three downs to retain possession of the ball.

The last of those changes had an immediate impact on the football field layout and longer-term effects on the tools used to monitor teams' progress in earning first downs. The rule-makers of 1882 added the requirement to stripe the field every five yards, primarily to assist referees in monitoring whether offenses gained the five yards in a possession. That five-yard ruler was sufficiently accurate for the open play of the 1880s, but the arrival of the closed, mass-and-momentum play of the 1890s meant football became a game of inches, and the five-yard stripes no longer provided the needed precision.

Enter the chain gang, whose equipment and procedures were defined for decades by custom and regional officiating organizations rather than the national rules committee. Football's rule-makers added a third officiating role -the linesman- in 1894 with few instructions for how one performed the role. We know some locations had people on the sideline manning the chains by then -the linesman's flag are mentioned in the rules of an 1894 board game- but it was not until 1898 that the rules committee recommended teams "…provide two light poles about six feet in length and connected at the lower ends by a stout cord or chain exactly five yards long." Two years later, they recommended the home team supply two assistants to operate those chains, at which point the linesman became known as the head linesman. The final significant change for the chains came in 1906 when a new rule required offenses to gain ten yards in three downs, forcing everyone to double the length of their stout cord or chain.

Since then, the chains have witnessed little change. Sure, some placed pennants atop the poles, others added lights or placed roundels atop the slightly taller poles, but today's chains look and function much like the original.

An interesting innovation to the chains was the long-forgotten Eckielipp chains had a second chain or rope several feet off the ground from which hung markers at one-yard intervals that helped referees and players assess the distance to gain on second, third, and fourth downs. Eckielipp chains seem silly on the surface, but they were used nearly four decades before Lockney Lines became common. (Lockney Lines are the short stripes running parallel to the yard lines near the hash marks and sidelines whose development is described here.) While Lockney Lines were a big hit in helping spectators understand the ball's location on the field, their original purpose, like the Eckielipp chains, was to help officials spot the ball following incomplete passes and penalties.

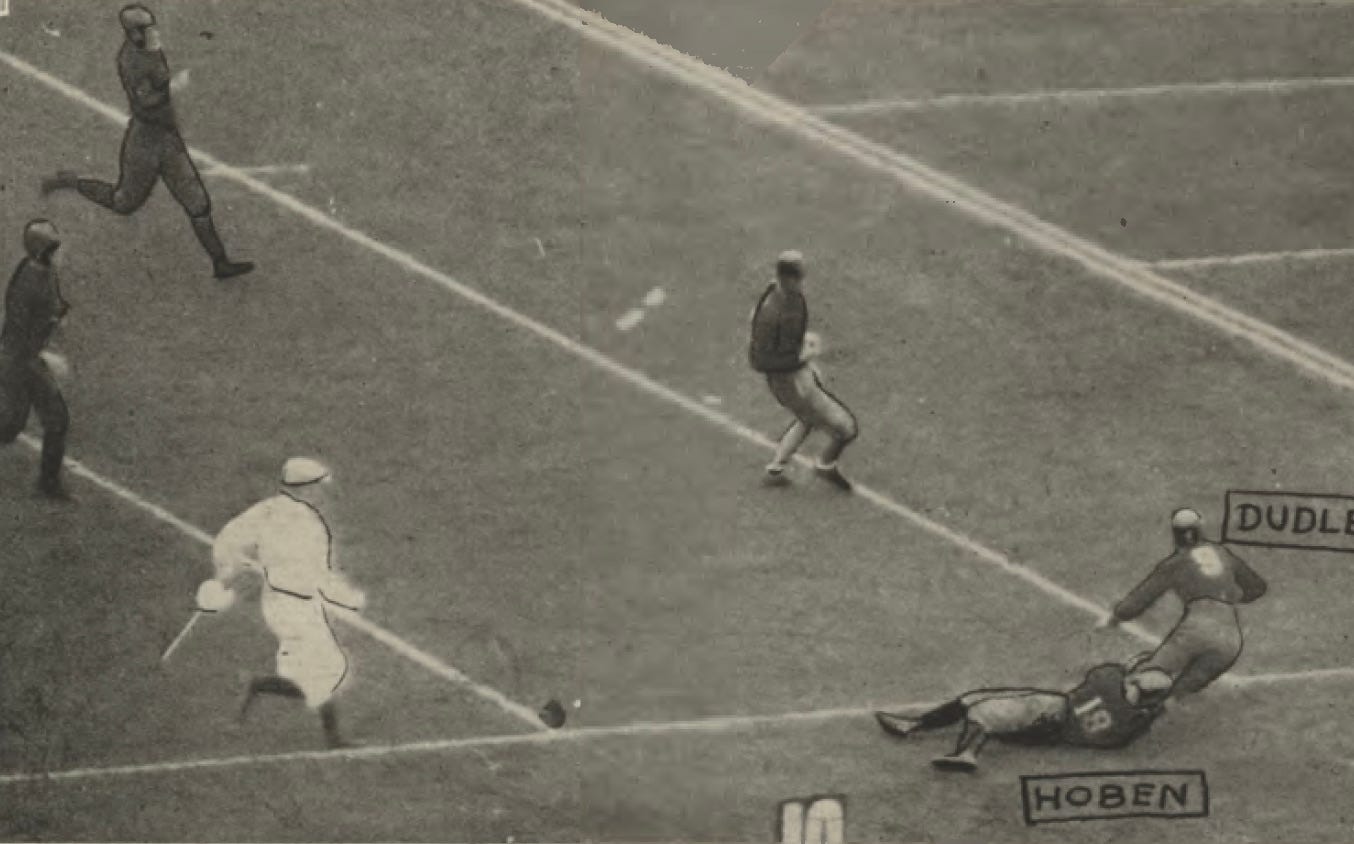

(Particularly attentive readers likely noticed the assistant linesmen on the right holds both a pole and a stick. Keep the stick in mind since we'll discuss it shortly.)

Of course, other than the Eckielipp version, football's chains only marked two spots: the point at which the offense started a set of downs and the point to be gained for a first down. The chains did not mark the ball's location on subsequent downs, the remaining yards to gain, or aid in spotting the ball following an incompletion or penalty.

How did early officials mark the spot of the down? Early officials dropped a handkerchief at the line of scrimmage, but those were subject to being moved by accident or stealth. Then someone had the idea to plant a stick or rod into the ground to mark the line of scrimmage. The rule-makers formally recognized this approach in 1907: "The Linesman shall mark the position of the ball on each down by using a short iron rod." The short iron rod, the precursor of today's down box, was sharpened on the bottom so the head linesman could plant it in the ground, keeping his hands free and allowing him to follow the play while the rod remained in place. For example, the image below shows an enterprising head linesman in a 1919 Nebraska game. He planted a pennant-topped rod on the field before inching toward the middle of the field to monitor the line of scrimmage.

After the move to four downs to gain ten yards in 1912, some head linesmen added a box to their sticks with the numerals 1, 2, 3, or 4 on the four sides, leading to the term "down box" entering football's lexicon.

The down box marked the spot of the ball and allowed the linesman to display the down by rotating the box so the numeral '1' faced the field on first down, the '2' faced the field on second down, and so on.

Both attentive and inattentive readers should recall the previously-noted assistant linesman with the second stick. The second stick supplemented the head linesman's stick and led to the addition of a third assistant linesman to man that stick. This second stick served an important purpose because head linesmen commonly picked up their sticks / down boxes and ran downfield to cover plays, ignoring their mothers' warnings not to run with scissors or sharp sticks. (More than a few players were injured by the sharp end of these sticks after colliding with the head linesman.)

F. A. Lambert, whose 1926 Football Officiating and Interpretation of the Rules was among the first books to detail consistent officiating procedures, argued against head linesman carrying sticks. He considered the stick dangerous and believed it better to have the assistant linesman manage the stick under the head linesman's direction. Others agreed, and the head linesman's stick ultimately disappeared from football fields.

Moving the stick or down box to the sideline and having it handled by someone who did not run around the field meant the down box could grow bigger and taller. That led to the next generation of down boxes displaying larger numbers on taller poles easily read by spectators and the press. Some locations placed the traditional four-sided box atop a tall pole; others placed four light bulbs on a pole with the number of illuminated bulbs corresponding to the down. Still others topped the pole with cards or plates that flipped to display the correct down in both directions. While the latter design coexisted with others for several decades, the flipping down markers became dominant. A wonderfully low-tech design, the flipping down box was easy to make and operate, and was readily visible by nearly everyone in the stadium.

Since then, tinkerers have developed chains and down boxes with sighting tools akin to surveyors. Others have advocated embedding electronic mechanisms in footballs to allow precise tracking as they move down the field. Still, the flipping down box, now largely replaced by louver-based systems, has stood the test of time, and the appearance of down boxes has seen little change in nearly a century.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.

Good stuff. The faux-precision of the 10-yard chains is one of the two weirdest relics of football that we still use. The fact that the original chain marker is marked by eye from 20+ yards away and then we measure within millimeters as needed is silly.

The other crazy relic is kicking specialists! We have big, strong fast athletes play on the field for 95% of the plays, and then bring in a kicking specialist to do something completely unlike the rest of the game, to often decide the outcome of games!