The First College Homecoming: 1909 Baylor

Small-town Americans living east of the Mississippi left home in the 1890s to settle open lands in the West and fill factory jobs in the Northern cities. So many people left home that those who remained back home began organizing festivals and reunions for former residents to return home for a weekend or week of concerts and other activities. Organized to encourage former townsfolk to come home, the events became known as homecoming, home-coming, or Homecoming. Louisville had one in 1906, Nashville in 1907, Sheboygan in 1909, and there were many others.

Homecoming events ultimately became tied to colleges and then high schools. School-related homecomings often featured a parade, class and group reunions, a dinner dance, and a football game. They also became annual rather than periodic events. Several colleges claim to have hosted the first college homecoming, and identifying which deserves the title requires us to consider the just-mentioned components that occurred on various college campuses in the past. Of course, alums had returned to campus for rivalry football games for decades but the schools did not position or refer to them as a homecoming.

Texas held a homecoming-like event in 1908 over Thanksgiving weekend, with Texas and Texas A&M playing on Thanksgiving Day, but that celebration honored the university's 25th anniversary. They also did not hold similar events in subsequent years, so Texas held a one-time event where alums and others came to campus but did not start Homecoming.

The situation gets stickier when considering Baylor's 1909 homecoming. That event was positioned solely as a social or fraternal activity for alums, with Baylor playing TCU in football that weekend. However, Baylor's next Homecoming did not occur until 1915, so their candidacy is also suspect.

That brings us to Illinois' campus in 1910, where Clarence Foss Williams and W. Elmer Ekblaw had the idea to hold a homecoming event each fall to bring former Illinois students back to campus. The two worked for several months building support with campus organizations and the administration, and they succeeded in holding the first school-sponsored Homecoming the weekend of October 15, 1910, capped by a win over Chicago.

Unlike their brethren from the Lone Star state, Illinois hosted a homecoming event each year from 1910 to the present other than canceling in 1918 due to the Spanish Flu pandemic.

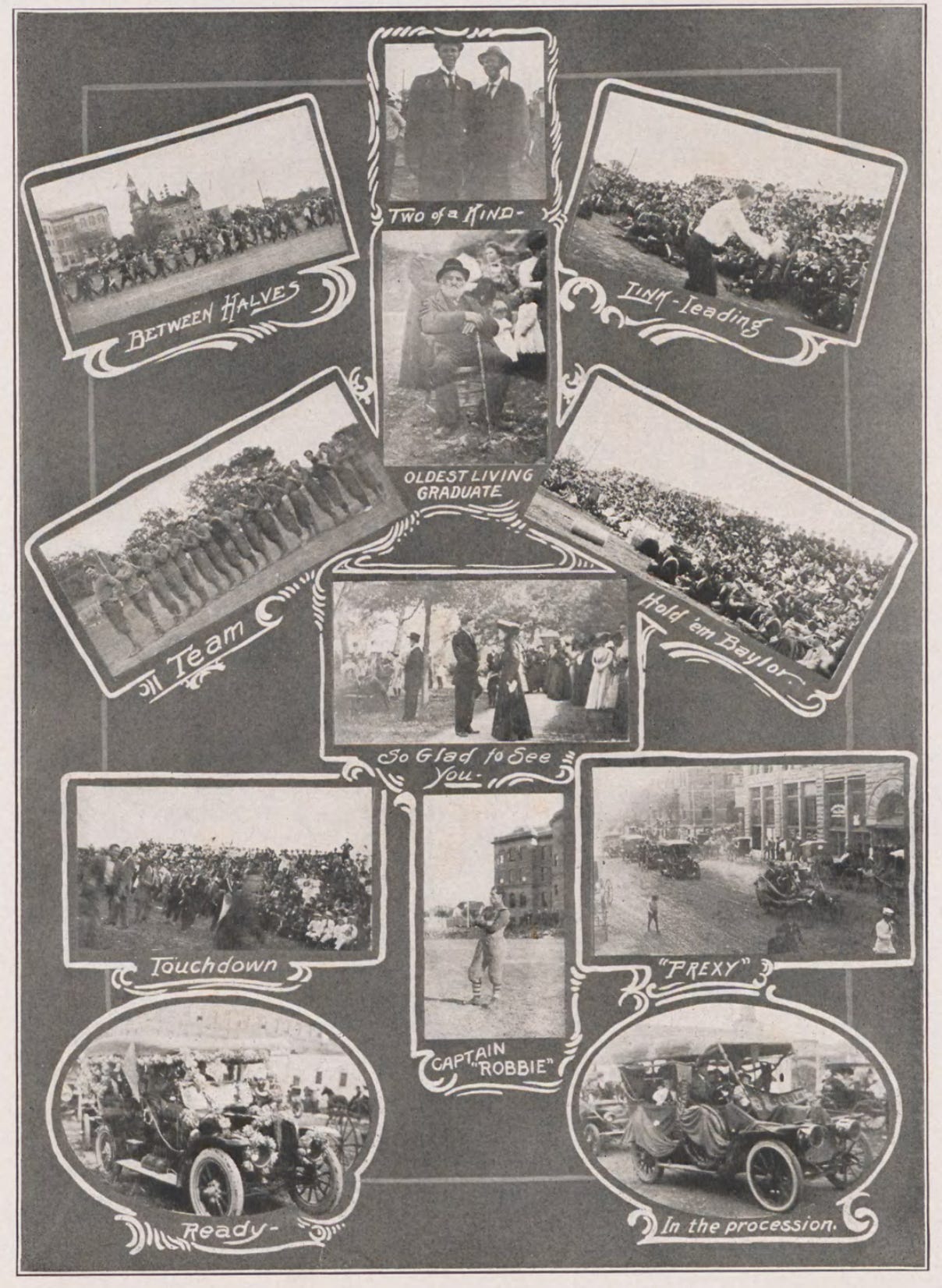

Which brings us to the point of the story. I had previously written about Texas, Baylor, and Illinois, so when I spotted the RPPC show below for sale, I pursued it. Thankfully, there was only one other bidder, so it cost me the equivalent of a six-pack of beer—very good beer.

Acquiring the RPPC led to more digging into the goings-on at Baylor's 1909 homecoming and the football team in the image. At the time, Baylor enrolled 1,500 students across the college, theological institute, and medical school. The organizers had Homecoming planning well underway a month in advance, and the word in Waco was that alumni groups from different cities and parts were fixin' to attend.

After all the planning, between 3,000 and 3,500 alums returned to Waco for the first-time event they called Homecoming on the Wednesday and Thursday of Thanksgiving week. I've never been to Waco, so I may be missing something, but that was a pretty good turnout for 1909.

As the alums crowded into Carroll Chapel that Wednesday evening for the welcome and opening talks, Baylor President Brooks offered honorary seating to those Baylor alums who attended the school before the Civil War. Thirteen alums took advantage of the offer, all of whom were in their late 80s or older at the time, giving college students in 1909 the opportunity to talk to people who had been adults when the Civil War started. If a college student in 1909 had known a centenarian while growing up, that person would have been born when Thomas Jefferson or John Adams was president, and they could have been a Washington baby.

Moving on to the football side of the story, Baylor's 1908 football team went 3-5, including an 89-0 loss to LSU, so the football following alums had to feel good that the 1909 team was 4-3 going into the Homecoming game against TCU. Of course, closer inspection would have revealed that Baylor had already lost to 5-1-1 TCU twice that season, going scoreless in recent 9-0 and 11-0 games. So, the pressure was there to play well in the Thanksgiving Day game in front of the biggest crowd the college had ever witnessed.

The style of team picture with the eleven starters posing in a line, one behind another, was popular in 1909. That was when the starters played all 70 minutes of the game, or nearly so. Back then, a game had two halves lasting 35 minutes apiece, changing the following year to a 60-minute match split into quarters. Nevertheless, the teams agreed to play 25-minute halves that day, so that's what they did.

It was a hard-fought game. TCU opened the scoring with a 35-yard first-quarter field goal after smartly choosing the wind. TCU's kicker was their center, so someone else had to long snap for him when he earned TCU's only score.

Baylor went scoreless until midway through the second half when they threw their only forward pass of the game, putting them within ten yards of the goal line. Two plays later, junior captain and left halfback T. P. Robinson ran it across, and quarterback Ernest Wilie kicked the extra point to give Baylor a 6-3 lead they did not relinquish.

The TCU team took the loss like champs or runners-up since the local newspaper commented on their attitude and the general merriment around town, saying:

The TCU boys received their defeat in the right kind of spirit, saying they were not so badly beat after all, and on account of the great gathering of homecomers victory was worth a great deal to the Baylor boys. This view and expression coming from the defeated team is certainly commendable.

Thanksgiving Day was generally observed in North Waco, all business being suspended in the afternoon and this part of the city presented itself like a Sunday.

'Losers Are Game,' Waco Times-Herald, November 26, 1909.

Everyone agreed that Baylor's Homecoming event had been a success. Still, as noted earlier, they did not welcome their alums back a second time until 1915, when Illinois had five homecomings under their belt. The Illini would also host the first Dad's Day in 1920, making them the celebration kings of the college world. Still, the Baylor folks had their day in 1909, which introduced us to the concept of college homecoming, while the folks at Illinois made it the tradition many of us have enjoyed over the years.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.