The First Southern Football Team to Play in the North: 1893 North Carolina

This article is a collaborative effort with James Gilbert. See below for James' profile.

Gridiron football was born among the Northeast and Middle Atlantic colleges, and those schools oversaw the game's early evolution. For forty-odd years, football's rules committee members came exclusively from those schools, and their alumni diaspora held most plum coaching jobs across the country. The region's schools also dominated on the field. The future Ivy League schools won more than ninety percent of games played before 1906 against future Big Ten, ACC, and similar competition. Everyone playing football during the period ultimately measured themselves against the best of the East.

Contests with schools from other parts of the country were infrequent due to the competitive imbalance and the cost and speed of travel. Michigan played most of the early intersectional games between Eastern and Midwestern schools. They visited Princeton and Yale in 1881, Cornell in 1889 and 1890, and Harvard in 1893, while UChicago visited Cornell in 1890. Somewhat delayed were games between Eastern and Southern schools, mainly because Southern colleges did not form teams until the late 1880s. Virginia and North Carolina, the powers of the South, fielded their first intercollegiate teams in 1888. They filled their schedules with schools and athletic clubs in their own or bordering states but soon began playing the southernmost of Northern teams: Princeton in New Jersey and Penn, Lafayette, and Lehigh of Pennsylvania.

The first North-South game came when Lehigh visited Virginia in 1889, winning 24-12. Virginia opened the 1890 season on Halloween against Penn in Washington, D.C. The not-yet-known-as Cavaliers lost to Penn 72-0 before heading to Baltimore the next day when Princeton stomped them 115-0. Virginia earned partial redemption three weeks later when visiting Lafayette lost 20-6, the first Southern victory over a Northern team. Finally, Penn beat Virginia 32-0 in 1893 in the fourth of nine shutouts that began Princeton's season.

Still, the five North-South games mentioned above occurred outside the states comprising the Ivy footprint. The first Southern team to invade the North was North Carolina when it traveled five-hundred miles to meet Lehigh on the Saturday before Thanksgiving 1893 at New York City's Manhattan Field. A late addition to the schedule, the background and story of the contest illuminate many elements of college football as the game gained popularity and spread across the country.

Founded in 1865, Lehigh's first intercollegiate games came in 1884, a season that included two losses to Lafayette. Lehigh tied Lafayette twice in 1885, lost twice in 1886, and split the series in 1887. Bitter rivals, Lehigh and Lafayette have played each other a collegiate-high 153 times as of 2020. Lehigh had 600 students in 1893 and was likely the wealthiest university in the nation, thanks to Asa Packer's donation of cash and railroad stocks. Like other teams of their area and era, Lehigh played a mix of Ivies and other top Eastern teams, along with their fair share of small colleges. Over the years, Lehigh won sixty percent of their games. They were good, not great, with ten years of playing experience entering the 1893 season when Harmon Graves, a former Yale halfback, was their rookie coach.

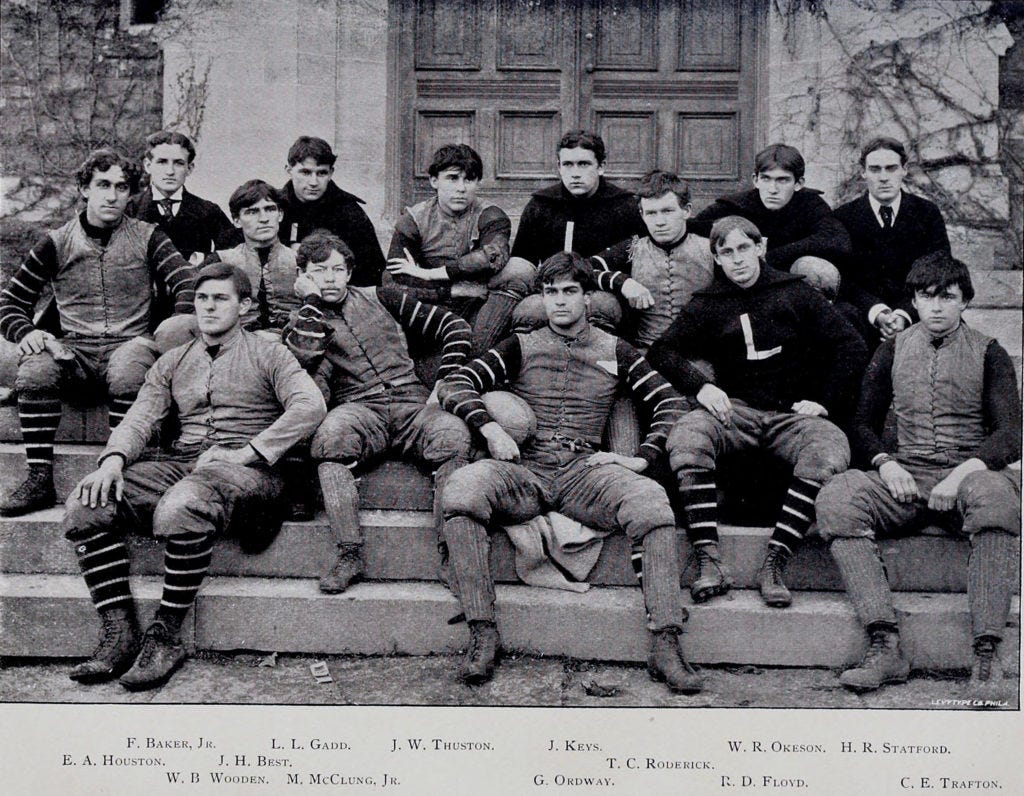

Lehigh had a rough start in 1893, opening with a lopsided win over Dickinson, then beating Army and losing to Penn in between two losses to Princeton. The Engineers then reeled off wins over Navy, Cornell, and Lafayette (twice), leaving them at 6-3. Despite the three losses, the New York Evening World viewed Lehigh as the fifth-best team in the country.

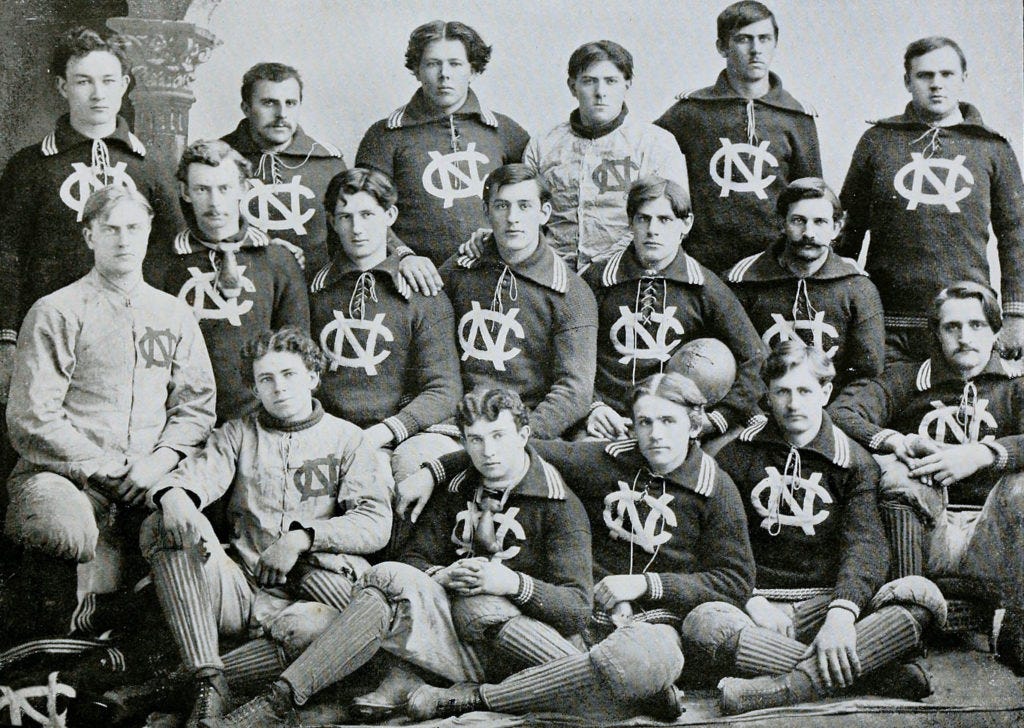

Whereas Lehigh was a child of America's industrial growth, the University of North Carolina was the public university of an agricultural state still dealing with the aftereffects of Reconstruction. Founded in 1789, the school had fewer than 400 students and no electricity when football practice began in 1893. In addition, the university was under pressure due to legislation calling for the school to provide graduate courses only, eliminating it as a competitor to the state's denominational colleges. Although universities offering both undergraduate and graduate degrees now dominate America's higher education system, that direction was not evident then. Hence, UNC's athletic teams came to symbolize the role and value of undergrads at Chapel Hill.

Despite many considering UNC the "Champions of the South" in 1892, they entered the 1893 season having played only thirteen football games in school history. Former Ivy players had come and gone as UNC's coaches. The informal, short-term coaching model was common then, though the movement to professional coaches had begun. Despite their limited tenure and challenges in finding consistent coaching, Virginia and North Carolina were considered the two best teams in the South. Rivals, the 1893 contest at season's end would mark the first of thirty-two times they played on football's rivalry day, Thanksgiving.

The 1893 UNC season was feast or famine with blowout wins over Washington & Lee, Tennessee, and Wake Forest, while losing tight, low-scoring games to VMI and Trinity (now known as Duke). The combination left them with a 3-2 record and an open date before their Thanksgiving Day game with Virginia. Lehigh had a game scheduled on November 25th with the Pittsburgh Athletic Club, but the game did not materialize for reasons unclear, leading Lehigh to challenge UNC to a contest. Most important, Lehigh arranged for the game at New York City's Manhattan Field, making it the first game played by a Southern team in the North.

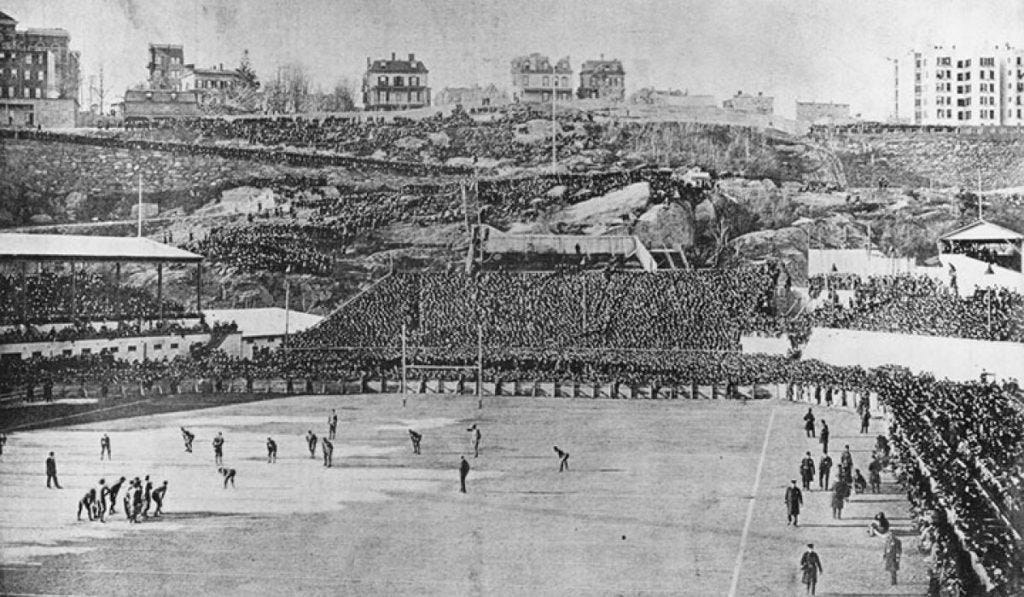

Although we think of regular-season, neutral-site games as emerging recently, they were widespread in the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th, particularly among schools in rural areas that could not draw sizable crowds. Chapel Hill had only 1,700 residents in 1890, and Bethlehem had 6,700, but Bethlehem had not been a destination city since Mary and Joseph's time. Many neutral site games occurred halfway between the competing schools or where the rail network provided access to both sets of fans. Most important, however, neutral-site games occurred in bigger cities because that's where the stadiums were, and, in this case, NYC had alums, friends, and others that might be interested in witnessing the battle between North and South.

The UNC team left Chapel Hill for New York City the Thursday night before the game, arriving Friday to check into the Savoy, then among Manhattan's top hotels, having recently hosted Princess Infanta Eulalia of Spain. Dr. Francis Venable, who chaired the meeting that formed the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association in December 1892 and was the team's faculty representative, arrived before the team. Venable was a well-regarded chemistry professor who, along with several football-playing lab assistants, was the first to identify calcium carbide, leading to the development of acetylene and the founding of Union Carbide. Venable briefed the press, telling them former Princeton player, Yup Cook, had schooled the Carolinians on the latest "scientific" football techniques, including the flying wedge and Woodruff's interference or "guards back" formation. The "guards back" formation positioned the guards in the backfield, allowing them to go in motion and plunge into the line as blockers. The rules of the day required only the center to be on the line of scrimmage and did not limit men in motion, leading to brutal strategies that later led to football's crisis of 1905-1906.

After a good night's sleep at the Savoy, the teams awoke to an unusually crisp Saturday morning and made their way fifty-some blocks north to Manhattan Field. Built several years earlier as the second Polo Grounds, it was renamed when they built the third Polo Grounds next door. The two stadiums sat across the Harlem River from today's Yankee Stadium and beneath Dead Head Hill, later known as Coogan's Bluff, where less well-heeled spectators or "Deadheads" paid a discounted fee to watch games from afar.

The day's newspapers vary in the reported size of the crowd that witnessed the game. Most reports suggest the crowd was smaller than expected, so UNC's share of the gate receipts made the trip north a less-than-profitable venture. But, there was a game to play between teams considered a reasonable match. Most, including UNC's student newspaper, expected the Tar Heels to show a fighting spirit and acquit themselves well in a losing effort. Still, the Tar Heel faithful and other Southern football fans knew a UNC win against a solid Northern opponent would send shock waves through the football world.

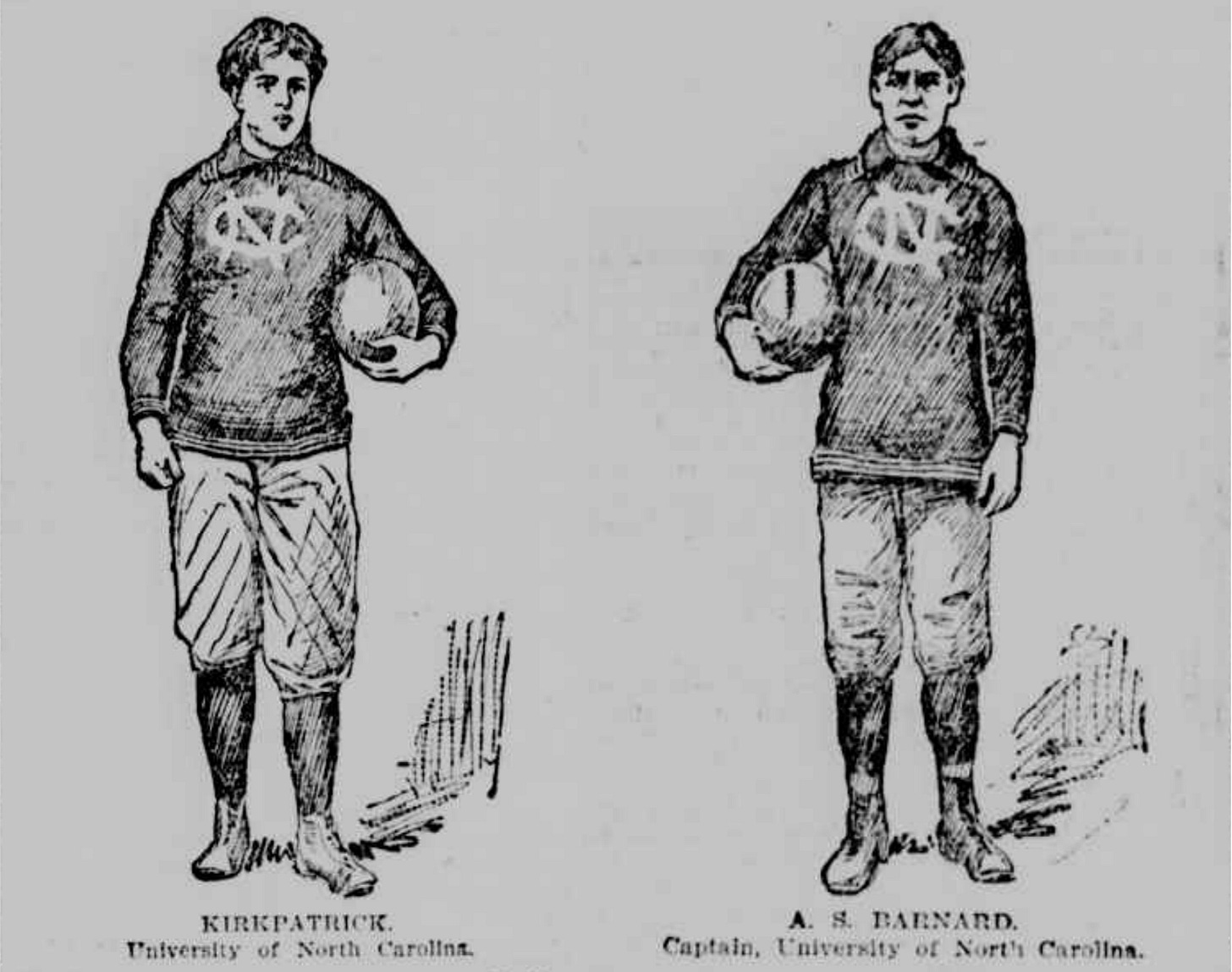

Lehigh won the toss and opted to give UNC the ball to kick, which meant UNC would be on offense first. Gridiron football's kickoff at the time resembled that of soccer today, so UNC kicked the ball a few inches, picked it up, and gave it to a runner whose teammates protected him inside a flying wedge. Unfortunately, UNC fumbled the ball, and Lehigh recovered. Several plays later, Lehigh scored and kicked goal to take a 6-0 lead (four-point touchdown and two-point kicked goal). On the next possession, UNC recovered from their early error, using interior runs to drive close to the opposite goal before fumbling again. Positioned near their own goal, Lehigh punted on first down to get themselves out of trouble, but UNC fumbled the return, with Lehigh recovering again. Lehigh scored for the second time several outside runs later, and the rout was on. Time and again, UNC ran the ball up the middle, attempting only three runs around end the entire game. Despite the athletic ability of UNC's Kirkpatrick and a few others, their unsophisticated attack did not match Lehigh's machine as the Engineers took an 18-0 halftime lead. Lehigh added sixteen more points in the second half to end the day as 34-0 victors.

Every team considers victory possible at kickoff, but the day proved disappointing for the Carolinians. Praised for their efforts, they, and Southern football, were not up to snuff at that point in the game's development. (They started getting their revenge several decades down the road.)

The UNC team's evening proved better than the afternoon thanks to the employer of an alum hosting a dinner at the Harvard Club, after which they took in the Broadway show Rip Van Winkle. Then, the Tar Heels got back on the train on Sunday, heading to Washington, D.C., where they spent a few days practicing before heading to Richmond and their Thanksgiving Day collision with Virginia, a game that ended in a 16-0 loss and a losing record for the Tar Heels' season.

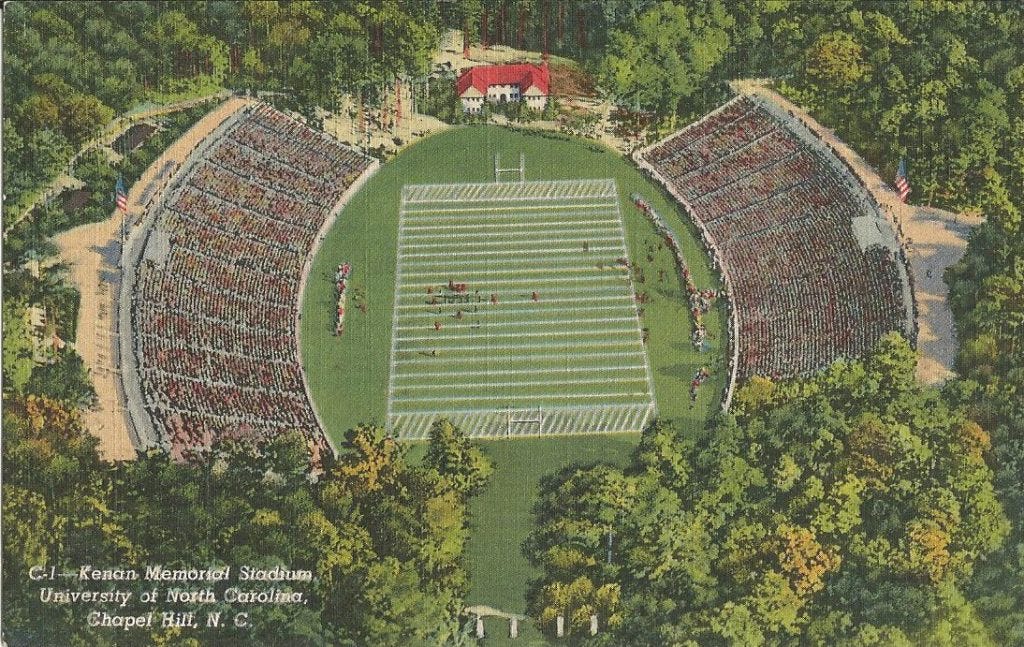

Although UNC failed to make a mark by beating a Northern team in the higher latitudes, an injury to a starting halfback in the Gotham City game resulted in William Kenan, Jr. coming in as a substitute and playing the remainder of the contest. While his contributions on the playing field for North Carolina were modest, his work as one of Venable's chemistry lab assistants led to a job with Union Carbide. Through hard work and marrying well, Kenan amassed a fortune that allowed him to fund the building of North Carolina's football stadium in 1927. Kenan Memorial Stadium remains UNC's home field today.

Kenan was not the only player at Manhattan Field that November day whose most significant impact on football was yet to come. Lehigh's All-America right end, Walter Okeson, became the player-coach of the first all-professional football team, the Latrobe Athletic Club, and was Lehigh's head coach in 1900 before turning his attention to officiating. Okeson worked big games and was central to organizing the training and assessment of Eastern officials in the 1920s. Okeson became a long-time member of the College Rules Committee, taking on the editorship of Spalding's Official Foot Ball Guide in 1934, a role previously held only by Parke H. Davis and Walter Camp.

Despite the pioneering intersectional game between Lehigh and North Carolina, similar regular-season games remained unusual until the advent of commercial airlines. Even after transportation advances eliminated travel time, the South's segregationist policies largely kept Northern teams from offering or accepting invitations to play Southern teams until those teams integrated in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

This article results from a collaboration with James Gilbert, UNC class of 1988, who worked at UNC for twenty-two years. James attended all but 1-and-a-half of UNC's 171 home football games between 1984 and 2011. Recently he compiled a Flickr album to document the location of the venues that hosted a UNC football game but no longer exists or hosts football games (https://flic.kr/s/aHsmNqDjQF). He also compiled Kenan Memorial Stadium's field designs from 1927 to present (https://flic.kr/s/aHsmDrRqs8).

Click here for options on how to support this site beyond a free subscription.