The sports term, doubleheader, originated from railroads using two engines to pull a long train. Baseball adopted the word to describe teams playing one another twice on the same day, and while double billings were once common in the big leagues, they are now played mostly by college, high school, and youth teams.

Doubleheaders were never common in football, but there have been several periods during which they were not unusual. One form of football doubleheader involved separate pairings of teams (team A versus team B and team C versus team D). Art Modell, the Cleveland Browns owner, arranged doubleheader NFL exhibition games at Cleveland Municipal Stadium during the early to mid-1960s. In the Modell model, fans purchased one ticket to see both games, which proved popular, drawing crowds of 80,000 or so each time.

The SEC took a different tack with doubleheaders in the 1960s and 1970s, often playing at Birmingham's Legion Field or Veterans Memorial Stadium in Jackson. Most doubleheaders included only SEC teams, while at least one saw Auburn host Oregon State and Alabama met California. Unlike the Modell model, the SEC doubleheaders required fans to buy separate tickets for the early afternoon and evening games.

As you might guess, however, that is not the end of the story, neither is it the beginning. Instead, there were several periods during which college teams played two opponents the same day, though every identified instance involved a higher-level team playing two lesser opponents. (My search for doubleheaders was not exhaustive, but I checked the schedules of twenty-five teams from across the nation and found nearly half had at least one doubleheader in their closet.)

Football's "real" doubleheaders occurred during the single-platoon era, with most played on the season's opening weekend. Playing a doubleheader generally involved the starters playing the better of the two opponents, while the second or third strings played the lesser visitor. (Besides the second string, college teams often had a reserve or scrub team functioning as the scout team for the varsity. Many reserve teams wore red jerseys in practice, leading to the term "redshirts.") Some coaches changed things up with the starters playing for a pre-determined portion of both games before turning things over to the reserves. A few teams mixed their starters and reserves to create balanced teams, much as some do for spring games today. Although most doubleheaders ended in two blowouts, some did not. The reserves periodically struggled to beat their opponent, and the first-stringers faced a few battles as well, and that is where things became interesting. (It is worth noting that both ends of the doubleheaders counted against the teams' official records then and now.)

The first identified set of doubleheaders involved Amos Alonzo Stagg's University of Chicago teams between 1898 and 1902. Each involved games against local high schools, which were not unusual for major college teams then. Doubleheaders disappeared for twenty years before reemerging on the West Coast. USC opened the 1922 season playing the U.S.S, Mississippi team in the afternoon and a USC alumni team that night. A few years later, the Trojans opened the 1925 season beating Whittier 74-0 and Cal Tech 32-0, leading to a never-to-be-repeated Los Angeles Times headline: "Trojans Clean Up On Poets and Engineers."

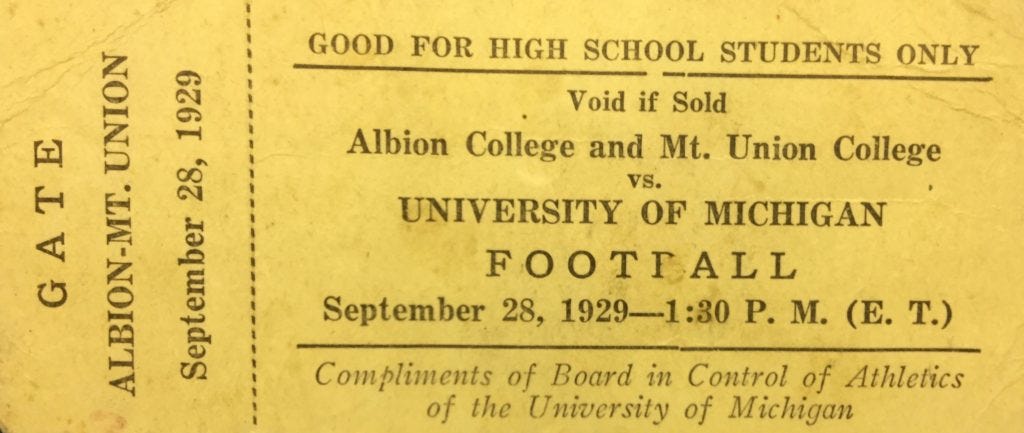

The 1929 season saw a relative explosion of season-opening double billings in the Big Ten. Chicago beat Beloit (27-0) and Lake Forest (9-6), Wisconsin pounded Ripon (22-0) and South Dakota State (29-0), and Michigan bested Albion (39-0) and Mt. Union (16-6). And then there was Indiana, who beat Wabash (19-2) in the opener, before the varsity was outplayed and outscored 18-0 by Ohio University in the second game of the day.

Many Big Ten teams played twin bills over the next few years, with Harvard joining in the fun in 1930 and Texas A&M doing so in 1931. Stagg was still at Chicago in 1931 when they beat Cornell of Iowa in the first game of the day before losing to Hillsdale in the afternoon cap. That was the last doubleheader Chicago played as it appears Stagg no longer saw the risk of a loss outweighing the value of tandem wins.

Doubleheaders reappeared on the West Coast in the early 1930s as USC, UCLA, and Cal took up the habit. USC and UCLA doubled up for several years, managing to shut out all their opponents, while Cal became addicted to doubleheaders, playing them annually from 1932 through 1939.

Cal-Davis was one of Cal's doubleheader opponents each of those years, scoring a total of six points through the 1938 game. Cal's other opponents included West Coast Navy, Nevada (twice), and Whittier, none of which scored a point. The University of the Pacific, coached by Amos Alonzo Stagg after his forced retirement from Chicago, became the preferred second opponent in 1936, with Pacific failing to score the first three years. That means Cal allowed six points in the fourteen doubleheader games played between 1932 and 1938.

The 1939 twin bill against Cal-Davis and Pacific was a different matter. Cal-Davis, the weaker of the two opponents, played the first game. The Bears' reserves started and played the first half against Cal-Davis, but were down 14-6 at halftime, so Stub Allison, Cal's coach, inserted his starters after the half. The first string scored twice that quarter, putting the score at 19-14 before yielding to the second string who played out the fourth quarter, winning 32-14.

The day's second game, Pacific versus Cal, began with several subplots. As mentioned earlier, Stagg's Chicago team lost to Hillsdale in 1931 when Chicago was heavily favored, so Stagg had been on the wrong end of a doubleheader game as the favorite and was now the underdog. Also, Stagg and Chicago had been upset in 1916 by tiny Carleton College, when Stub Allison was a starting end for Carleton. Perhaps the combination gave Pacific the mojo, but Stagg clearly wanted the upset in his fiftieth year as a head coach.

Of course, the more direct explanation for what happened next was the fact that Cal's first-stringers had to unexpectedly play a full quarter against Cal-Davis and then faced a fresh and motivated Pacific team. In any event, Pacific controlled the game, playing stifling defense, outgaining Cal on offense, and recovering three fumbles lost by the same Cal punt return man. Pacific crossed the goal line in the third quarter to take a 6-0 lead and was driving inside the ten as the final gun sounded. The victory allowed Stagg to return the favor of Allison's victory over him as a player and offset his loss as the favorite in a Chicago doubleheader.

The potential for upsets contributed to the end of football doubleheaders, as did the state of world affairs. Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, leading to college men entering the Armed Forces as volunteers and later as draftees. That led to reduced roster sizes, rules allowing unlimited substitution, and, ultimately, two-platoon football. Although two-platoon football disappeared from the college game in the 1950s, doubleheaders did not resurface, and the economics of the game preclude their return anytime soon.

The unused ticket atop the page was intended for Michigan's 1930 doubleheader with Denison and Michigan State Normal College, now Eastern Michigan. (Courtesy of Jack Briegel)

If you enjoyed this article, consider subscribing to my newsletter or check out my books.